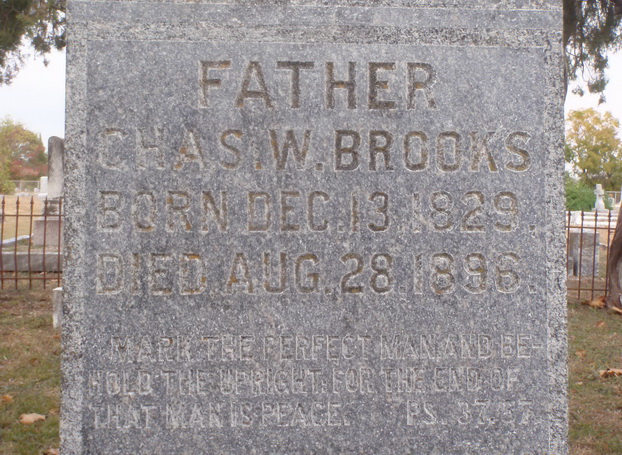

11. Charles Wesley Brooks was born 13 December 1829 in Lawrence County, Alabama, and died 28 August 1896 at Georgetown in Williamston County, Texas. The date of birth is stated in the register of a bible that may have belonged to Charles’s father James Brooks and then passed to James’s son James Irwin Brooks, or perhaps belonged originally to the latter, who copied information from the register in his parents’ bible into his own family bible. Charles’s tombstone in Odd Fellows cemetery at Georgetown in Williamson County, Texas, also gives 13 December 1829 as his date of birth.[1]

A biography of Charles’s son John Lee Brooks, a Dallas attorney, in A History of Texas and Texans states that John’s father Charles Wesley Brooks was born in Florence, Lawrence County, Alabama, on 25 December 1830.[2] Note that Florence is in Lauderdale and not Lawrence County, Alabama, and that the corroboration of the bible register’s date of birth by Charles’s tombstone suggests that the date recorded in the bible and on the tombstone and not the one found in John Lee Brooks’s biography is correct.

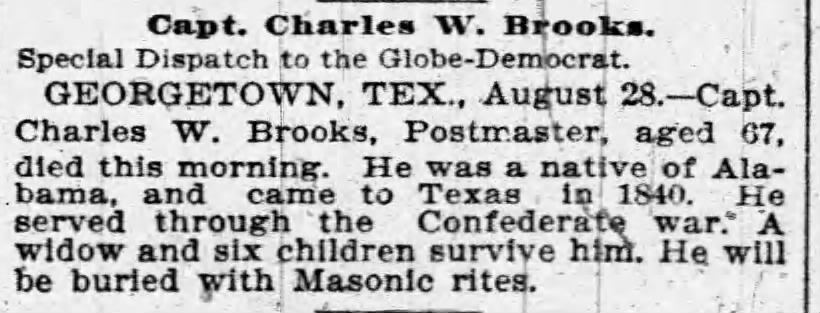

Charles’s date of death, 28 August 1896, is recorded on his tombstone, which appears to have been erected soon after his death.[3] A notice of Charles’s death appeared in the St. Louis Globe Democrat on 29 August 1896, stating that Capt. Charles W. Brooks had died 28 August 1896 in Georgetown, Texas, aged 67.[4] The previously cited biography of Charles’s son John Lee Brooks erroneously states that John’s father Charles died 28 August 1898.[5] The information about Charles W. Brooks in the biography of his son John appears to have been supplied by John himself, by the way. A biography of Charles’s son Richard Edward Brooks, also in A History of Texas and Texans, transposes the final two numerals in his father’s date of death and states that Charles died in 1869.[6] As with the biography of his brother John, it appears Richard, a Texas judge who helped found and headed the Texas Fuel company and then Producers Oil Company, supplied the information for his biography.

Charles’s Move to Bastrop County, Texas, from Alabama, 1854

According to the biographies of both John and Richard, their father Charles W. Brooks came to Bastrop County, Texas, from Alabama in 1854, bringing with him enslaved persons belonging to Judge Dick Townes (so the biography of Richard states) or of Judge John C. Townes (the name given by John’s biography). John’s biography states (see image at top of the page),

In his early youth Mr. Brooks became an overseer and planter by profession. He came to Texas in 1854, in his twenty-fifth year, bringing fifty slaves to Texas for Judge John C. Townes, Sr., father of Judge John C. Townes of Austin, Texas, and opened a 600-acre plantation for the elder Townes on the Yeghua Creek, below Manor, in Bastrop County, Texas.[7]

Richard’s biography says,

The father of Judge [Richard Edward] Brooks was Charles Wesley Brooks, who was born in Alabama and came to Texas in 1854 from that state. He brought to Texas the negro slaves of Judge Dick Townes, and after establishing a farm for Judge Townes in Bastrop County, and after the arrival of the Townes family in that locality, he engaged in farming for himself, and was one of the prosperous and successful men of his community up to his death in 1869.[8]

The 1850 federal census verifies the information of John Lee Brooks’s biography that his father Charles was an overseer at the time he moved to Texas. Charles is enumerated in 1850 in Lawrence County, Alabama, in the household of Elijah McDaniel, with Charles’s occupation listed as overseer — for McDaniel, it seems certain.[9] The census gives Charles’s age as 20 (transcribers have misread the number as 26; the 20 is not clearly written, and is easily mistaken for 26). The 1850 federal slave schedule shows Elijah McDaniel holding 21 enslaved people in Lawrence County in that year.[10]

As a previous posting has noted, a 1 May 1877 letter sent by Sarah Lindsey Speake of Lawrence County to her sister Margaret Lindsey Hunter in Red River Parish, Louisiana — Sarah and Margaret were daughters of Dennis Lindsey and Jane Brooks, an aunt of Charles Wesley Brooks — mentions Elijah McDaniel. Among the pieces of information Sarah sends to her sister Margaret is the news that James Dennis Lindsey, son of Fielding Wesley Lindsey and Clarissa Brooks, had bought the old Elijah McDaniel place. As has been previously noted, Clarissa was a sister of Charles Wesley Brooks who married Fielding Wesley Lindsey, brother of Dennis Lindsey who married Jane Brooks.

A biography of Elijah McDaniel’s grandson William T. McDaniel, a dentist of Athens, Alabama, states that his grandfather Colonel Elijah McDaniel (1796-1868) was a native of North Carolina who moved as a young man to Danville, Alabama, spending the rest of his life there engaged in planting.[11] The 1860 federal agricultural schedule shows Elijah holding 440 acres of cultivated land in Lawrence County’s southern division and 1,000 acres of uncultivated land.[12]

The Judge Dick Townes for whom Charles Wesley Brooks brought enslaved people to Texas and opened up a plantation was Eggleston Dick Townes (1817-1864) of Franklin County, Alabama. The 1850 federal slave schedule shows E.D. Townes holding 22 enslaved people in Lawrence County and 35 enslaved people in Franklin County where he lived.[13] The Judge John C. Townes mentioned in the biography of John Lee Brooks was John Charles Townes (1852-1923), a son of Eggleston Dick Townes.

Eggleston Dick Townes was a Virginia native who graduated from University of Alabama with a B.A. in 1835, and then studied law at the university and was admitted to the bar.[14] In 1851, he was elected chancellor of the Northern Chancery Division of Alabama, a position he held until the following year, when he resigned it. By 1856, he had moved to Texas, settling east of the community of Manor in Travis County near the Bastrop County line. As his biography in Handbook of Texas states,

By 1860 Townes was one of the wealthiest men in Travis County and listed his profession as planter in that year’s census. He had a real estate value of $20,000 and personal estate value of $30,000. He owned a slave plantation with an overseer named William Sherling of Arkansas and owned fifty slaves ranging in age from six to sixty.[15]

In 1859-1861, E.D. Townes represented Bastrop, Burnet, and Travis Counties in the Texas Senate, and he served from Travis County in the Texas House of Representatives in 1861-3.[16] E.D. Townes’s son John Charles Townes, mentioned in John Lee Brooks’s biography, had a distinguished career as a lawyer in Austin and Georgetown, Texas, and was a law professor at University of Texas and first dean of its school of law.[17] His papers are held by the Tarlton Law Library of University of Texas at Austin.[18]

Turning back to Charles Wesley Brooks: interestingly, he shows up on the 1850 federal census twice, once, as we’ve seen, as Elijah McDaniel’s overseer in Lawrence County, Alabama. But C.W. Brooks also appears on the 1850 agricultural schedule in Bastrop County, Texas, owning 30 acres of improved land on which he had 60 horses, 25 milk cows, and 30 other cattle, and on which he was growing wheat, rye, and oats.[19] Note the predominance of cattle and horses: as we’ll see in subsequent documents, Charles’s primary interest in farming in Texas appears to have been ranching, an interest his wife Elizabeth Burleson Brooks shared, as we’ll discover when we focus specifically on her life.

Charles’s Cousin Alexander M. Brooks and His Prior Move from Alabama to Bastrop County, Texas

Charles already had a foothold in Bastrop County by the time he settled there in 1854, a rather impressive one for a young man of 21 who had not yet married and was living several states away. What accounts for that, one wonders? In fact, he had a first cousin in the county who had moved there previously from Lawrence County, Alabama, and was prospering — Alexander Mackey Brooks (1808-1899), son of Charles’s uncle Thomas Brooks and wife Sarah Whitlock.

We’ve met Alexander M. Brooks in numerous previous postings (if you click on his name in the tags below, they’ll all pop up). But this previous posting, in particular, has information pertinent to the story of how his cousin Charles Wesley Brooks may have ended up settling in Bastrop County, Texas, after Alexander did. As it notes, Alexander was a business partner of William Burke Lindsey, son of Mark Lindsey and Mary Jane Dinsmore, in Lawrence County, Alabama — Burke being a brother to Dennis Lindsey who married Alexander’s sister Jane, to Dinsmore Lindsey who married Alexander’s sister Sarah, and to Wesley Lindsey, who married Charles Wesley Brooks’s sister Clarissa. On 2 July 1835 in Lawrence County, Alexander married Carolina Puckett, a niece of Oakville’s leading merchant Major Richard Puckett.[20]

In the fall of 1838, Alexander left Carolina and went to Texas, with rumors subsequently circulating that Burke and Carolina had been involved with each other,[21] and with the business Alexander and Burke were conducting together faltering. Carolina subsequently sued for a divorce on grounds of abandonment, and the Alabama legislature granted it to her.[22] She then married Burke Lindsey and they moved to Tishomingo County, Mississippi.[23]

Alexander, meanwhile, settled in Bastrop, Texas, by 1846, having lived a while in Houston prior to that, while building a house in Bastrop in 1842 as he anticipated moving there — a house now on the National Register of Historic Places.[24] On 1 January 1849 at Jane Elizabeth Hogan’s “Round Top” boarding house in Houston, he married Aletha Sorrells, who had outlived four husbands prior to Alexander.[25] Officiating at their wedding was Reverend Rufus Burleson, who was later president of Baylor University. All of this information is documented in the posting I pointed you to in the last link above, and I plan to say more about it and about Alexander when I discuss the children of Thomas M. Brooks and wife Sarah Whitlock down the road.

Note the name Rufus Burleson: In 1855 in Bastrop County, Charles Wesley Brooks would marry Elizabeth Christian Burleson, daughter of James Burleson and Mary Randolph Buchanan. Rufus was James’s nephew. By the time Charles W. Brooks arrived in Bastrop County, that’s to say, not only had a Brooks first cousin of his settled in the county’s seat of Bastrop, where he was doing well for himself, but that cousin had a tie to the Burleson family, a family into which Charles Wesley Brooks would marry a year after moving to Bastrop County.

It seems clear to me that there was a connection between Alexander and his first cousin Charles that accounted for the latter following Alexander to Bastrop County, Texas. It’s even possible, I think, that either Alexander or Charles or both urged Eggleston Dick Townes to settle near Manor, Texas, and to open a plantation there.

Charles’s Marriage to Elizabeth Christian Burleson, 1855

As noted above, the biography of Richard Edward Brooks in A History of Texas and Texans states that after Charles W. Brooks had established a farm for Judge Dick Townes and the Townes family had then arrived in Texas, Charles began farming on his own.[26] The biography of Richard’s brother John contains more information about this matter: it states,

Soon after completing this work [of opening a plantation for Eggleston Dick Townes], and over Judge Townes’ protest, he left the latter’s employ, and in 1854 married Elizabeth (“Bettie”) Burleson, youngest sister of Gen. Edward Burleson, prominent in Texas history as a pioneer Indian fighter, at the battle of San Jacinto, vice president of the Republic of Texas under Sam Houston, and great-uncle of Albert Sidney Burleson, postmaster general, and one of the mainstays in President Wilson’s cabinet.[27]

The date of Charles’s marriage to Elizabeth Christian Burleson was actually 9 May 1855, not 1854.[28] Subsequently, the biography of John Lee Brooks states that Charles W. Brooks and Elizabeth Burleson married in Elizabeth’s twentieth year, 1855, at the home of her older half-sister Martha, wife of Sherman Reynolds in Bastrop County.[29]

The biographies of both Richard Edward and John Lee Brooks contain extensive information about the Burleson family, a family connection of which both men were obviously proud. Richard’s biography states that the Burleson family was “one of the most historic families of Texas,” and that Elizabeth was the youngest daughter of James Burleson, “whose name will always have a distinguished place in Texas annals.”[30] The biography states that James Burleson came to Texas in 1831, “settling in Bastrop County, and taking an active part in the pioneer life of the province and the subsequent Republic of Texas.”[31] It also states that during the invasion of Texas by Santa Anna, Elizabeth had been carried to safety by her mother. Richard’s biography speaks as well of General Edward Burleson, “the most noted member of the family and brother of Mrs. Brooks,” who succeeded Stephen Austin as commander of Texas troops at the siege of San Antonio in 1835.[32]

Historian Kenneth Kesselus transcribes a 4 February 1844 letter of Edward Burleson to M.B. Lamar, who was collecting information for a history of Texas; the account is from the Lamar Papers (History of Bastrop County, Texas, Before Statehood [Austin: Jenkins, 1986], pp. 43-5). The letter states that in 1831, General Burleson founded a settlement below Bastrop. Kesselus says this is the first account of early settlers of Bastrop County.

John Lee Brooks’s biography suggests that he was especially proud of his Burleson blood, and characterizes him as “a Burleson to the bone,” with the square jaw and facial expression of that family, their brown eyes, and the restless energy and keen intellectual activity characteristic of the Burlesons.[33] John’s biography contains several pages of Burleson history, noting that his mother Bettie Burleson was born near old Fort Bastrop on 11 April 1835, and descended from the Burlesons, Buchanans, and Christians.[34] Her grandfather Thomas Christian was killed in Bastrop County while surveying land near Manor just prior to the war for Texas’s independence. And her father James Burleson, “a noted Indian fighter,” died as a result of wounds he received in battle with native Americans in the early 1830s.[35] (Note that Elizabeth Burleson was not actually a Christian descendant: her mother Mary Randolph Buchanan married first Thomas Christian, and following his death, James Burleson, father of Elizabeth.)

Extensive information about General Edward Burleson and his brother Aaron follows, with a note, too, that Elizabeth Burleson Brooks’s cousin Dr. Rufus C. Burleson was “widely known and his memory deeply revered as one of the great pioneer Baptist preachers of Texas.”[36] The biography notes that Rufus Burleson’s “fame as a writer and educator is inseparably bound up with the founding and history of Baylor University.”[37]

This is, of course, the same Reverend Rufus Burleson who married Alexander M. Brooks and Aletha Sorrells (Hope) (Freel) (Patterson) (Pierce) in Houston in 1849, six years before Alexander’s cousin Charles married Rufus’s cousin Elizabeth Burleson. What the biographies of Richard and John Brooks do not note is that the Burlesons moved to Texas having previously lived in Lawrence County, Alabama — Lawrence County also being the home of Alexander and Charles Brooks before they came to Texas.[38] And that Elizabeth Burleson’s mother Mary Randolph Buchanan (1795-1870) was born in Wythe County, Virginia, where Alexander and Charles’s fathers Thomas and James Brooks had lived before moving to Kentucky and then to Alabama….[39] When Charles Brooks and Bettie Burleson married in Bastrop County, Texas, in 1855, their families already had thick ties and shared history.

Richard Edward Brooks’s biography notes that his family was “among the more prosperous people of Texas” as he was coming of age.[40] The biography of Richard’s brother John states that the land his father Charles W. Brooks farmed in Bastrop County, Texas, came to him in part (I suspect largely) from his marriage to Elizabeth Burleson. If the family of Charles W. Brooks had resources, those appear to have come largely from the Burleson family. John’s biography states,

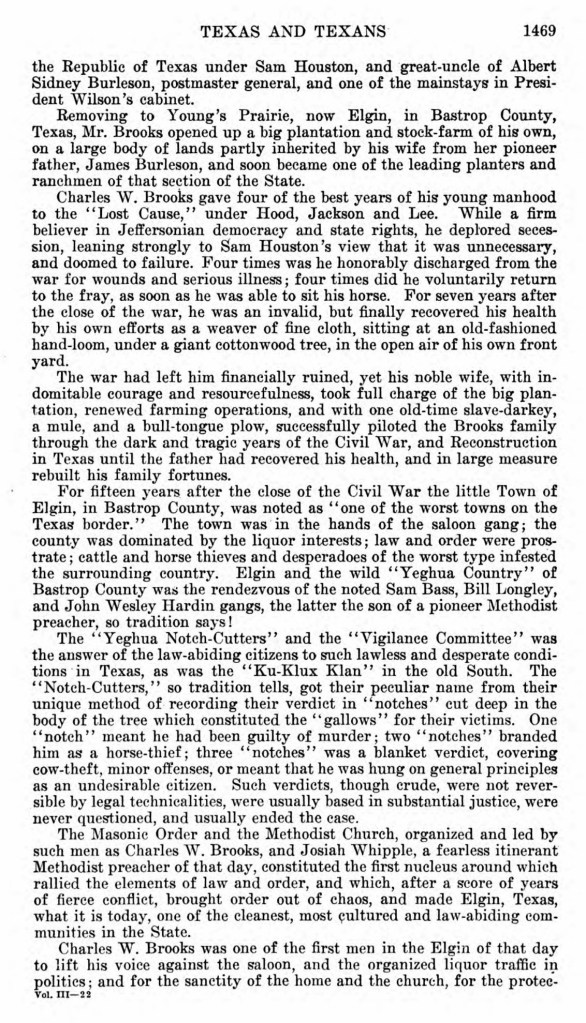

[After his marriage to Elizabeth Burleson], [r]emoving to Young’s Prairie, now Elgin, in Bastrop County, Texas, Mr. Brooks opened up a big plantation and stock-farm of his own, on a large body of lands partly inherited by his wife from her pioneer father, James Burleson, and soon became one of the leading planters and ranchmen of that section of the State.[41]

Bastrop County deed records show Charles’s new wife Elizabeth buying land from her mother a year afrer she and Charles married — evidently the Young’s Prairie property on which he opened his stock farm aftere marrying Elizabeth. On 7 June 1856, Mary Burleson sold Elizabeth Brooks for $700 two tracts in Bastrop County adjacent to the survey of Mary’s Buchanan family, one with 100 acres and the other with 250 acres (Bastrop County, Texas, Deed Bk. K, p. 561). Mary signed the deed with no witnesses, and acknowledged it the same day. It was recorded 2 September 1857.

In 1857, Charles bought more land in Bastrop County. On 28 January 1857, he bought from George J. Glasscock of Travis County for $300 100 acres on Sandy Creek, out of George J. Glasscock’s headright grant (Bastrop County, Texas, Deed Bk. L, pp. 197-8). Glasscock signed by George with witnesses B.F. Hall, R.A. Boyce, and Benjamin King, and King proved the deed in Bastrop County on 22 January 1859 and it was recorded on 27 January.

Charles and wife Betty then sold these 100 acres on Sandy Creek for $600 to William F. McWilliams on 12 January 1859, with the deed stating that the land was east of the Colorado River on waters of Sandy Creek (Bastrop County, Texas, Deed Bk. L, pp. 375-6). Both Charles and Betty signed, acknowledgint the deed on 11 June 1859; it was recorded. 3 October 1859.

The 1860 federal census further suggests to me that the financial resources of the family of Charles and Elizabeth had much to do with her Burleson family. The census shows the family farming in precinct 6 of Bastrop County, with Char. W. Brooks listed as a farmer, 31, born in Alabama, and wife Betty as 25, born in Texas.[42] In the household are children Thomas W., 4, Itasca Ann, 2, and Texanna, 10 months, all born in Texas. Also living with the family in 1860 was Elizabeth’s widowed mother Mary, 65, a widow born in Virginia. Mary’s real worth is given on the census as $2,000 and her personal worth as $250, while Charles has a personal worth of $2,200.

Charles’s Civil War Service in 17th Texas Infantry (CSA)

According to the biography of his son John, Charles served as a Confederate soldier under Hood, though he deplored secession, leaning strongly to Sam Houston’s belief that it was misguided and would lead to failure.[43] The biography indicates that Charles was discharged from his service four times for wounds and illness, each time returning as soon as he was able to sit his horse. It adds that for seven years after the war, he was an invalid, spending those years weaving cloth with an old-fashioned hand loom set up under a giant cottonwood tree in his front yard.[44]

Charles’s Civil War service record shows him enlisting on 21 June 1862 at Camp Terry in Austin in the 17th Infantry unit that Robert T.P. Allen had organized at that camp in March 1862.[45]

Charles’s age at enlistment was 33, and his service file shows him absent due to illness for much of the time he served as a private in Allen’s regiment. The date of his discharge is difficult to read in the service packet; I believe it was January 1863. Also serving with Charles in the 17th were Elizabeth Burleson Brooks’s cousins Edward B. Burleson, son of Jonathan Burleson, and John B. Burleson, son of Aaron Burleson.

Colonel Robert T.P. Allen was a West Point graduate who had founded Bastrop Military Academy in Bastrop prior to the war.[46] As Bruce Bumbalough states, the 17th Infantry wintered at Camp Nelson in Little Rock in 1862-3 and had heavy casualties from disease.[47] Bumbalough cites a member of the 17th, Benajah Harvey Carroll, who became a Baptist minister following the war, who stated that the 17th Infantry lost more men from measles and pneumonia in the winter of 1862–3 than from all the battles in which it was engaged.

After the War

Johnson’s biography states that during the period of Charles W. Brooks’s infirmity following the Civil War, his wife Bettie managed their farm with the assistance of a man formerly enslaved.[48] According to the biography, Elgin, where the Brooks family lived in these years, was noted for lawlessness, with saloons contributing much to the lawlessness. The biography states that, in concert with the Masons and his Methodist church, Charles led a crusade against the saloons in these years, often doing so from the chair in which he sat as he wove cloth.[49] During this time, he was foreman of the county’s grand jury, and was often threatened as he served in that position, according to his son’s biography. The biography recounts an occasion on which he stood against a brick wall while opening his shirt to show his wounds from the war, daring those threatening him for doing his duty as jury foreman to “shoot the heart out of an ex-Confederate soldier, a Mason, a Methodist, and a free-born Texas and American citizen.”[50]

On 6 January 1867, C.W. Brooks and wife Elizabeth sold to Jacob H. Perkins, all Bastrop County, for $200 farm lots 50, 51, 52, and 55 in the town of Bastrop, with the deed noting that these lots had come to Elizabeth Burleson Brooks from her father James Burleson Jr. (Bastrop County, Texas, Deed Bk. N, pp. 321-2), Both signed and acknowleded the deed on 6 February 1867, when it was recorded.

The 1870 federal census suggests that the Brooks family had held onto at least some of its resources during the turbulent period of the war and its aftermath. This census lists Ch. W. Brooks as 39, born in Alabama, a farmer in Bastrop County with $1,200 real worth and $1,000 personal worth.[51] Wife Elizabeth (Elisb. on the census) is 35, born in Texas. In the household are children Itasca, 13, Texana, 11, Nancy, 9, Edward, 6, and James, 3, all born in Texas.

Charles appears on the 1870 federal agricultural census in Bastrop County farming 201 acres of improved land, with 276 unimproved acres, with 60 horses, a mule, 14 milk cows, 2 oxen, 20 other cattle, and 30 swine, all livestock valued at $1,000.[52] He also grew 200 bushels of corn yearly on his farm. Again, note that Charles was primary ranching on the prairie land of Elgin, and not growing crops. The corn would have been to feed his livestock.

On 24 August 1870, Charles bought from his cousin Alexander M. Brooks for $500 500 acres in Bastrop County, the northeast corner of the Joseph Martin headright (Bastrop County, Texas, Deed Bk. P, pp. 455-6). Alexander signed and acknowledged the deed in Houston on 19 September 1870. He had bought the land on 17 August for $500 from Leander C. Cunningham, with the deed stating that on that day, Alexander produced satisfactory evidence that the deed had been lost and Cunningham confirmed the deed — so this may be a tract that Alexander had purchased earlier, to which he received title when he made payment on 17 August 1870.

On 6 June 1872, George W. Jones and J.D. Sayers sold C.W. Brooks, all Bastrop County, for $300 500 acres from the Joseph Martin headright east of the Colorado River about 18 miles northeast of the town of Bastrop (Bastrop County, Texas, Deed Bk. R, pp. 227-8). Jones and Sayers both signed with witnesses W.A. Standifer, Richard Berger, William M. Spittler (for Jones), and J.C. Buchanan for Sayers. On 22 July, Standifer proved the deed and it was recorded 25 July.

Later in 1872 on 5 November, 5 November 1872, William B. Moore sold CW. Brooks, both of Bastrop County, for $700 70 acres from the Enock Harris league survey (Bastrop County, Texas, Deed Bk. T, pp. 28-9). Moore signed and acnowleged the deed on the day it was made, and it was recorded 30 August 1873.

On 10 November 1879, C.W. and Elizabeth Brooks sold John Wolfe, all of Bastrop County, for $600 150 1/6 acres out of the Martin tract in Bastrop County (Bastrop County, Texas, Deed Bk. I, pp. 156-7). The deed states that this land adjoined the 500-acre tract deeded to C.W. Brooks by A.M. Brooks. Both Charles and Elizabeth siigned, and both acknowledged the deed on 10 December 1879. It was recorded 6 January 1881. Note that the biography of Charles and Elizabeth’s son John states, as indicated below, that the family moved to Georgetown in Williamston County in the fall of 1878, but this deed identifies Charles and Elizabeth as living in Bastrop County in November 1879.

The Move to Georgetown, Texas, and Charles’s Final Years

According to his son John’s biography, in the fall of 1878, Charles moved his family to Georgetown in Williamson County, Texas, so that his children could have the educational advantages offered by that community. He then enrolled the children who were of age to be schooled in the preparatory department of Southwestern University.[53] John Lee Brooks’s biography notes that he was in the Southwestern preparatory academy from age 12-14, and he then graduated from the university in 1893; the biography of his brother Richard states that Richard also graduated from Southwestern.[54]

Southwestern had been founded in 1870 through the merger of four Methodist colleges.[55] The school then officially opened at Georgetown as the state’s first university in 1873, several years before Charles moved his family to that community so that his children could be educated at Southwestern.[56]

The 1880 federal census lists Charles’s children Nannie and James Robert as students in addition to their siblings Richard and John, so it appears that these two children of Charles were also enrolled at Southwestern after the family moved there. The family is enumerated in 1880 at Georgetown in Williamson County, where C.W. Brooks is listed on the census as a farmer born in Alabama, aged 50.[57] Wife B.D. Brooks is 44, born in Texas, keeping house along with daughter T.C. (Texana Crosby), who is 20. Also in the household are children Nanie R. (Nannie Roline), 18, R. (Richard Edward), 16, James R. (James Robert), 13, J.L (John Lee), 10, M.C. (Mary Cassandra), 7, and C.W. (Charles Wesley), 5, all born in Texas. The census reports that Charles’s parents were both born in North Carolina. As we’ve seen previously, North Carolina may have been the birthplace of Charles’s mother Nancy Isbell, but his father James Brooks was born in Frederick County, Virginia.

The only deed I find for Charles W. Brooks in Williamson County is one showing him buying a strip of land in Georgetown from Jacob Hemphill on 27 January 1880 (Williamson County, Texas, Deed Bk. 24, p. 362). Charles paid $16.32 for the land, which Hemphill had bought from J.J. Dimmitt. The land started at Dimmitt’s northwest corner and Hemphill’s southwest corner on University Street. On the day of the sale, Hemphill acknowledged the deed and it was recorded 2 March 1880. I think this must be a record of Charles purchasing a lot or part of a lot in Georgetown on which the family lived after moving there.

After moving to Georgetown, George and wife Elizabeth continued engaging in land transactions in Bastrop County. On 23 May 1882, John Warren of Brazos County sold C.W. Brooks of Williamson County for $30 140 acres from the Joseph Martin league in Bastrop County east of the Colorado River (Bastrop County, Texas, Deed Bk. 3, pp. 26-7). The deed mentions the 500-acre tract conveyed to Brooks by Jones and Sayers on 6 June 1872. Warren acted through an attorney F.A. Orgain for the land sald. Orgain proved the deed in Bastrop County on the day of the deed and it was recorded 28 May.

On 5 October 1882, C.W. Brooks and wife Bettie sold T.C. Cooper of Bastrop County for $400 a tract, acreage not given, east of the Colorado River on Sandy Creek from the Joseph Martin headright league (Bastrop County, Texas, Deed Bk. 8, pp. 521-3). Charles and Bettie both signed with Charles acknowledging the deed in Bastrop County on 25 October and with Bettie acknowledging it in Williamson Countyon 5 December. It was recorded 20 April 1886. The deed gives Bastrop County as Charles and Elizabeth’s residence, though they were living in Georgetown in Williamson County by this time.

On 1 March 1883, C.W. Brooks of Williamson County sold William F. Cruse for $400 100 acres from the Joseph Martin survey about 16 miles northwest of Bastrop in Bastrop County (Bastrop County, Texas, Deed Bk. 5, pp. 132-3). Charles signed and acknowledged the deed in Bastrop County the day of the deed and it was recorded 14 November 1883.

On 10 May 1883, Charles W. Brooks of Williamson County formed a firm with Richard Vaughn Standifer of Bastrop County, with an agreement that the firm of Brooks and Standifer would co-own two tracts of 1,280 acres each on the Colorado River in Lampasas County, Texas, belonging to Standifer, the Dorsey W. Biggs tract and the Francis C. Wilson tract. Charles paid $3,160 for his share of the partnership.[58] On 1 November 1884, Standifer then deeded Brooks an outright half share of both tracts of land for $3,000.[59] An obituary of Standifer from the Lampasas Leader on 1 June 1889 at his Find a Grave memorial page in Elgin cemetery, Bastop County, identifies him as a merchant of Elgin.[60] Richard V. Standifer and Charles W. Brooks were linked through the family of Charles’s wife Elizabeth Burleson: Richard Standifer married Sarah Texana Gatlin, whose mother Nancy Wright Christian was a half-sister of Elizabeth Burleson.

On 5 June 1883, C.W. and Bettie Brooks of Williamson County sold Harry E. Taylor of Bastrop County for $750 250 acres from the Thomas Christian headright league, east of Colorado River on the prong of Willbarger Creek (Bastrop County, Texas, Deed Bk. 5, 610-611). Both Charles and Bettie signed and on 14 October 1883 in Williamson County, both acknowledged the deed, which was recorded 26 April 1884.

On 24 July 1885, John Wolf(e) of Bastrop County sold C.W. Brooks of Williamson County for $200 82 acres on waters of Sandy Creek in Bastrop County (Bastrop County Deed Bk.7, pp. 393-4). The deed gives Wolf’s name as John, but he signed as Thos. Wolf. It shows John Wolf acknowledging the deed on 25 July 1885, It was recorded 14 August 1885.

On 22 July 1885, Charles W. Brooks of Williamson County sold C.W. Stanfield of Bastrop County for $900 70 acres in Bastrop County from the Enock Harris league (Bastrop County, Texas, Deed Bk. 7, pp. 608-9). Charles acknowledged the deed in Bastrop County on the day it was made, and it was recorded 7 November 1885.

John Lee Brooks’s biography states that when John was 14 years old (in 1884), he went to his father’s ranch near Fort San Saba on the Colorado River in Lampasas County and spent four years working there to build his strength. The biography also notes that John entered Vanderbilt University on a scholarship in the fall of 1893, studying theology and modern languages until his health broke in 1897, at which time he returned to his father’s Lampasas County ranch for a year and then spent a year as postmaster at Georgetown, succeeding his father in that position for several years.[61]

On 23 April 1894, Charles W. Brooks was appointed U.S. postmaster for Georgetown, with an announcement on 11 April in the Austin American-Statesman noting that he had been nominated for the position.[62] The record of Charles’s appointment in NARA’s Record of Appointment of Postmasters, 1832-1971 shows that, as the biography of Charles’s son John states, John succeeded his father as the Georgetown postmaster after Charles’s death.

John’s biography notes that his father died while serving as Georgetown postmaster and was buried in the Odd Fellows Cemetery at Georgetown, where his grave is marked by “a noble granite shaft.”[63] Underneath an inscription that gives Charles’s name (Chas. W. Brooks) and dates of birth and death, the tombstone states, “Mark the perfect man and behold the upright for the end of man is peace. Psalm 37.37.”[64]

John Lee Brooks’s biography contains a lengthy eulogy of Charles written, it seems clear, by John himself. It states (see image at top of the page):

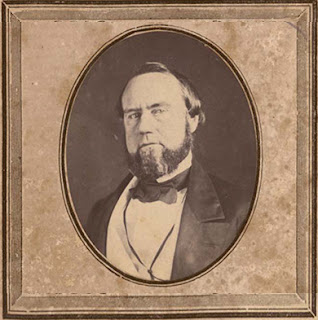

Charles Wesley Brooks’ name was a synonym of honor and integrity, and a passport to his children wherever he was known. He did much of his large and extensive business on his word of honor, which was as good as his bond. He was a man of fine physique and commanding appearance. He stood over six feet in his sock feet, and in his prime was a man of fearless courage and great physical prowess. He was a man of strong native ability, of sound business judgment, and scientific planter, stock-raiser, and an expert horticulturist. He was a good veterinary surgeon, and, but for the misfortune of having his education cut short by family reverses, he would undoubtedly have achieved great wealth and distinction, as a man of the highest integrity, force of intellect and character. He was a life-long Mason, a Methodist, and a staunch Jeffersonian democrat, a teetotaler, but a militant believer in and champion of local option and state rights. He took little stock in national prohibition, nor in woman’s suffrage. He deplored “a short-haired woman” or a “crowing hen!” and often prayed: “From such, good Lord, deliver us!”[65]

In a subsequent posting, I’ll discuss what John Lee Brooks’s biography tells us about his mother Elizabeth Burleson Brooks, and what various sources discussing the life of Elizabeth’s mother Mary Buchanan (Christian) (Burleson) have to tell us about her connection to Charles and his wife Elizabeth.

[1] See Find a Grave memorial page of Charles Wesley Brooks, Odd Fellows cemetery, Georgetown, Williamson County, Texas, created by John Christeson, with tombstone photos by John Christeson.

[2] Frank W. Johnson, A History of Texas and Texans, vol. 3 (Chicago and New York: American Historical Society, 1916), p. 1468. The biography of John Lee Brooks is more extensive than the excerpts I’m quoting in this posting, which focus on his parents. The complete biography, which focuses largely on John himself, runs from pp. 1466-1484.

[3] See supra, n. 1.

[4] “Capt. Charles W. Brooks,” St. Louis Globe Democrat (29 August 1896) p. 2, col. 5.

[5] Johnson, A History of Texas and Texans, vol. 3, p. 1470.

[6] Frank W. Johnson, A History of Texas and Texans, vol. 4 (Chicago and New York: American Historical Society, 1914), p. 1641.

[7] Johnson, A History of Texas and Texans, vol. 3, p. 1468.

[8] Ibid., vol. 4, p. 1641.

[9] 1850 federal census, Lawrence County, Alabama, district 8, p. 401a (dwelling/family 514; 20 November).

[10] 1850 federal slave schedule, Lawrence County, Alabama, district 8, p. 12 (19 November).

[11] See Albert Burton Moore, History of Alabama and Her People, vol. 2 (Chicago and New York: American Historical Society, 1927), p. 120.

[12] 1860 federal agricultural schedule, Lawrence County, Alabama, southern division, Moulton post office, p. 13.

[13] 1850 federal slave schedule, Lawrence County, Alabama, district 7, p. 61 (2 December); 1850 federal slave schedule, Franklin County, Alabama, district 5, unpaginated (18 December).

[14] See James A. Hathcock, “Townes, Eggleston Dick (1817-1864),” Handbook of Texas, online at website of Texas State Historical Association.

[15] Ibid.

[16] See Wayne Schneider, “Eggleston Dick Townes,” at his website, Manor, Texas – Past and Present – Parts and Pieces.

[17] See Seymour V. Connor, “Townes, John Charles (1852-1923),” Handbook of Texas, online at website of Texas State Historical Association.

[18] See “Guide to the John C. Townes Papers, 1887-1923,” at Texas Archival Resources Online (TARO) website.

[19] 1850 federal agricultural schedule, Bastrop County, Texas, precinct 1, unpaginated.

[20] Lawrence County, Alabama, Orphans Court Marriage Bk. B, p. 158.

[21] See the diary of Rev. Samuel Andrew Agnew, an Associate Reformed Presbyterian minister of northeastern Mississippi, who stayed with Burke and Carolina in Tishomingo County on 3-4 August 1854, then returned home to write scurrilous gossip about them in his diary. The diary is held by held by the Southern Historical Collection at University of North Carolina’s Wilson Library (Chapel Hill), and is available digitally at the website of Southern Historical Collection.

[22] See Marilee Beatty Hageness, Alabama Divorces 1818-1868: State Legislature (priv. publ., 1995), p. 4.

[23] See Ancestry’s “Alabama, Select Marriage Indexes, 1816-1942,” pointing to Limestone County, Alabama, Marriage Licenses, License Records and Bonds, 1832-1952. This set of records is not available digitally through FamilySearch.

[24] See Drury Blakeley Alexander, Texas Homes of the Nineteenth Century (Austin: Univ. of Texas Press, 1966), photo 95.

[25] Information about the marriage is in a 1 November 1895 affidavit that Alexander M. Brooks provided in Houston for a lawsuit in Brazos County, Texas, in which Mary J. Harriman et al. were suing D.C. Giddings, et al. A valuable manuscript compiled by George W. Glass, “Hope Family Notes and Miscellaneous Notes on the James Hope Family,” held by the Clayton Memorial Library in Houston contains notes about this case. Glass was a grandson of Mary Jane Harriman, the principal plaintiff in the case. This Glass collection is available digitally at the FamilySearch site (here, here, and here).

[26] Johnson, A History of Texas and Texans, vol. 4, p. 1641.

[27] Ibid., vol. 3, pp. 1468-9.

[28] Bastrop County, Texas, Marriage Bk. 1, p. 89.

[29] Johnson, A History of Texas and Texans, vol. 3, p. 1472.

[30] Ibid., vol. 4, p. 1641.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid. It should be noted that Edward and Elizabeth Burleson were half-siblings: Edward was a son of James Burleson by his first wife Elizabeth Shipman, and Elizabeth was a daughter by James’s second wife Mary Randolph Buchanan, the widow of Thomas Christian when the couple married.

[33] Ibid., vol. 3, p. 1474.

[34] Ibid., p. 1471.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Ibid., p. 1472.

[37] Ibid.

[38] See James Edmond Saunders, Early Settlers of Alabama (New Orleans: Graham & Son, 1899), p. 72, which states that the Burlesons moved from North Carolina to east Tennessee, and had settled in middle Tennessee by the time of the Creek War. James Burleson and his brother Joseph then settled in Lawrence County, Alabama, before the native peoples living there were removed, with James settling on the north side of a mountain at Fox Creek. The Burlesons then had a bellicose relationship to the Cherokees in their vicinity, and it was after James killed several Cherokees that he fled to Missouri and then settled in Bastrop County, Texas, in 1831. According to Byron Howard, “difficulties with the Indians in Alabama” caused the Burlesons to move to the Missouri Territory in 1816 and then to Hardeman County, Tennessee, in 1825, and from there to Texas: see “Burleson, James, Sr. (1775–1836),” Handbook of Texas, at the website of Texas State Historical Association.

[39] See Byron Howard, “Burleson, Mary R.B. Christian (1795-1870),” Handbook of Texas, at the website of Texas State Historical Association.

[40] Johnson, A History of Texas and Texans, vol. 4, p. 1641.

[41] Ibid., vol. 3, p. 1469.

[42] 1860 federal census, Bastrop County, Texas, precinct 6, p. 265 (dwelling 443/family 406; 7 August).

[43] Johnson, A History of Texas and Texans, vol. 3, p. 1469.

[44] Ibid.

[45] See NARA, Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Texas, RG 109, digitized at Fold3.

[46] See Bruce Bumbalough, “Seventeenth Texas Infantry,” Handbook of Texas, at the website of Texas State Historical Association.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Johnson, A History of Texas and Texans, vol. 3, p. 1469.

[49] Ibid., pp. 1469-1470.

[50] Ibid., p. 1470.

[51] 1870 federal census, Bastrop County, Texas, Bastrop post office, p. 462A (28 June).

[52] 1870 federal agricultural census, Bastrop County, Texas, p. 4.

[53] Johnson, A History of Texas and Texans, vol. 3, p. 1470.

[54] Ibid., pp. 1474-5; and vol. 4, p. 1641.

[55] Edwin M. Lansford, Jr., “Southwestern University,” Handbook of Texas, at the website of Texas State Historical Association.

[56] William B. Jones, To Survive and Excel: The Story of Southwestern University, 1840-2000 (Georgetown: Southwestern University, 2006), pp. 76f.

[57] 1880 federal census, Williamson County, Texas, Georgetown, p. 435B (ED 156; family 223; 13 June).

[58] Lampasas County, Texas, Deed Bk. I, pp. 558-9.

[59] Ibid., Deed Bk. M, p. 255.

[60] See Find a Grave memorial page of Richard Vaughn Standifer, Elgin city cemetery, Bastrop County, Texas, created by Scott Lackey.

[61] Johnson, A History of Texas and Texans, vol. 3, p. 1474.

[62] See NARA, Record of Appointment of Postmasters, 1832-1971, RG28; available digitally at Ancestry in the collection, U.S., Appointments of U. S. Postmasters, 1832-1971; and Austin American-Statesman, 11 April 1894, p. 5, col. 3.

[63] Johnson, A History of Texas and Texans, vol. 3, p. 1470.

[64] See supra, n. 1.

[65] Johnson, A History of Texas and Texans, vol. 3, p. 1468.

Charles Wesley Brooks was Worshipful Master of our Post Oak Island Masonic Lodge #181 in 1864, 1871, 1872, 1873, 1875 and 1876. Does anyone have a photo of him. We would like to place it on our wall of Worshipful Masters. My name is Trey Smith and me email is texian1838@yahoo.com. Thanks

LikeLike

Thanks for your interesting comment. I haven’t run across a picture of Charles, unfortunately. I wonder if there is a photo of Charles in the papers of his son John Lee Brooks which are, I understand, held by the library or archives of SMU. That might be a place to contact.

LikeLike