Or, Subtitled: Cittles, Chears, Coffy Pots, and Canters: What Can Be Gleaned from an Estate File

Dennis Lindsey’s Estate Documents: Prefatory Comments

Estate or probate files (or, in Louisiana, they’re called succession files) can, in my experience, run the gamut from genealogically astonishing — they can name all the heirs of the decedent and identify them as full or half-siblings, for instance — to disappointing. Too many of my ancestors left wills naming “my wife and all my children,” and estate files that show their estate being inventoried, appraised, and sold, without including any division of the proceeds of the estate naming the heirs of the decedent.

Dennis Lindsey’s estate file[1] falls somewhere in the middle between astonishing and disappointing, in my estimation. Its biggest disappointment is that it does not specify Dennis’s heirs. It does, on the other hand, provide some valuable clues about at least one probable son, Mark, and about a probable brother, William Jr. It also provides a very interesting snapshot of the social and familial milieu in which he lived — names of neighbors, probable relatives, and others with whom he and his family interacted in the community around what would later become Woodruff, South Carolina, between Jamey’s and Ferguson’s Creek of the Tyger River in southern Spartanburg County, South Carolina. One of the fascinating things the snapshot shows us is that people who had taken the Loyalist side during the Revolution were interacting freely with those — like Dennis and his father William — who had given service in the Revolutionary cause.

The South Carolina upcountry was very much divided between those supporting the American side in the Revolution, and those who remained loyal to the British. As historian Robert Stansbury Lambert tells us, the Revolution was a virtual civil war in South Carolina, and especially in the upcountry. According to Lambert, the largest concentration of Tories in the state was in Ninety-Six District, in which the Lindsey family lived.[2] Historian C.L. Bragg echoes Lambert’s analysis, noting that Scots-Irish settlers were especially inclined to take the British side, and that Ninety-Six District had the highest percentage of Loyalists outside Charleston.[3]

Some of the names we’ll encounter in Dennis Lindsey’s estate file are names of families who had sided with the British. As I’ve noted in previous postings, Mark Lindsey, a very likely son of Dennis, married Mary Jane Dinsmore, whose father David, a Scots-Irish settler on Jamey’s Creek, was a Loyalist soldier who was exiled to Nova Scotia after Charleston fell to the Americans. William Lindsey Jr., who is, I believe, a brother of Dennis married Margaret Earnest, whose father Henry Earnest was also a Loyalist. The estate records of Dennis Lindsey capture a moment not long after the war in which neighbor had gone to war against neighbor, but in which those same previously bellicose neighbors were now gathered to buy property at an estate sale in seeming accord.

The Documents in the Estate File

That said by way of preface to an examination of the documents in Dennis Lindsey’s loose-papers estate file (see note 1 below for information about the file), here are the documents we find in that file:

- The first item in the file is the bond given by Dennis’s widow Mary Lindsey with Nathaniel Woodruff and William Moore, dated 12 January 1795 (see above). Mary signs the bond by mark, and the two bondsmen sign their names. Written on the back of the bond is the is date 7 January 1795. The bond states that administration had been “lately” given by the county court to Mary, the widow.

I assume that the 7 January 1795 date is the date on which the county court gave administration of the estate to Mary, though I have not seen court minutes stating this specifically.[4] If that’s correct, then Dennis had died before 7 January 1795. This means that he might have died late in 1794, in fact, sometime after 10-11 March, when Dennis shows up as a buyer at the estate sale of David McCulloch in Laurens County. The appeal to administer an estate was not always made immediately after someone died, but in some cases, several weeks later.

Note one of the other questions the bond raises: what was Mary Lindsey’s relationship to Nathaniel Woodruff and William Moore? As I’ve noted previously, the 1790 and 1800 federal censuses show Dennis’ father William Lindsey enumerated next to William Moore as well as to members of the Woodruff family who were cousins of Moore’s wife Hannah Woodruff. Dennis Lindsey also appears to be closely connected to the Woodruff family in various documents. But the fact that Mary chose Nathaniel Woodruff and William Moore as her bondsmen might well tell us that she, too, had some close connection to the Woodruffs, something I’ll discuss in more detail in a posting discussing Mary and Dennis’s son Dennis Jr.

- On the same day (12 January 1795) that Mary Lindsey gave bond with Nathaniel Woodruff and William Moore to administer the estate, Spartanburg court issued a warrant for George Bruton, William Moore, and John Woodruff to inventory and appraise the estate. The back of the warrant states that all three appraisers gave oath on 11 February. This is the second document in the estate file.

As I have noted previously, Nathaniel Woodruff (1719-1805) was father of the Joseph Woodruff who, with his son Thomas, was a founding settler of the community that became Woodruff, South Carolina. Nathaniel joined his sons Nathaniel (1740-1822), Joseph, Thomas, Samuel, and John in Ninety-Six District (later Spartanburg County), and is thought to be buried with Joseph and wife Anna Lindsey in the old Bethel cemetery attached to what is now First Baptist church of Woodruff. The John Woodruff appointed to inventory Dennis Lindsey’s estate is probably John, son of Nathaniel Sr. The Nathaniel Woodruff with whom Mary gave bond to administer the estate could be either Nathaniel Sr. or Jr.

George Bruton is, of course, the man of that name to whom Dennis Lindsey had deeded half of his 248-acre grant between Jamey’s and Ferguson’s Creek by bond in 1792 — on that document, see the previous posting.

- The third document in the estate file is Bruton’s, Moore’s, and Woodruff’s inventory and appraisal of the goods and chattels of the estate. This was done 4 February 1795 and filed 11 February, with all three men signing the appraisal document. The appraisal was filed at April court 1795. Here’s a summary of the inventory and appraisal, without the appraisal values that one can find in the original document above:

1 black mare; 1 brown mare; 3 head cattle; 1 wheel and reel; 1 woman’s saddle; 1 man’s saddle; 1 pair saddle bags; 2 big wheels; 2 pair old chains and hangings; 1 ax and hoe, 2 clevises; 1 shovel plow; 2 iron pots, 1 dutch oven; 3 water vessels, 1 sifter; 1 tea kettle (“Cittle”); 2 chairs (“chears”); 1 wine canter; 1 case of razors; 4 drinking glasses; 9 teacups and saucers, 2 teapots, 1 mug; 1 coffee (“Coffy”) pot and 6 delph plates; 36 weight pewter; 1 set knives, 2 forks; 5 tin cups, 2 padlocks; five old knives, 3 old forks; 1 spur, 1 gimlet, corkscrew; 1 belt buckle; 1 table; 1 testament (i.e., bible), 1 hymn book; 1 large trunk; 1 bed, 2 blankets, 2 sheets; 2 old blankets, 1 bed cover; 1 hog, 4 rawhides; 1 coffee mill; wearing clothes, 15 garments. The total amount of the appraisal is £36 7s 2(?)d.

Though it seems Dennis Lindsey did not own land and though he deeded away his 248-acre land grant (see the last posting) this inventory suggests that he and his family were not impoverished. A wine decanter, Delph plates, a coffee pot and teapots: these were items that went beyond the realm of basic necessities. The testament (i.e., bible) and hymn book also testify to Dennis’s literacy, something about which we already know from the notes written in his hand that are found in his South Carolina Revolutionary audited account file.[5]The bible and hymn book also suggest he and his family may have been members of a church, though if that’s the case, I have found no information about the church to which they belonged. I have not found them in the minutes of Jamey’s Creek/Bethel Baptist/Woodruff Baptist church, and by the generation of Mark Lindsey — if I am correct that Mark is Dennis’s son — at least one branch of the family were Methodists from the early 1800s.

The household furniture listed in the inventory and appraisal (e.g., one bed, two chairs) also suggests that Dennis’s family was not large. If Mark Lindsey was Dennis’s son, then it’s likely he had married (about 1793, it seems) and was not living in the household. If Dennis also had a son Isaac, I think that Isaac may have left his father’s household by this point, too. It seems likely that only Dennis’s son Dennis (1793-1855/1860) was living at home with Dennis and wife Mary when Dennis Sr. died.

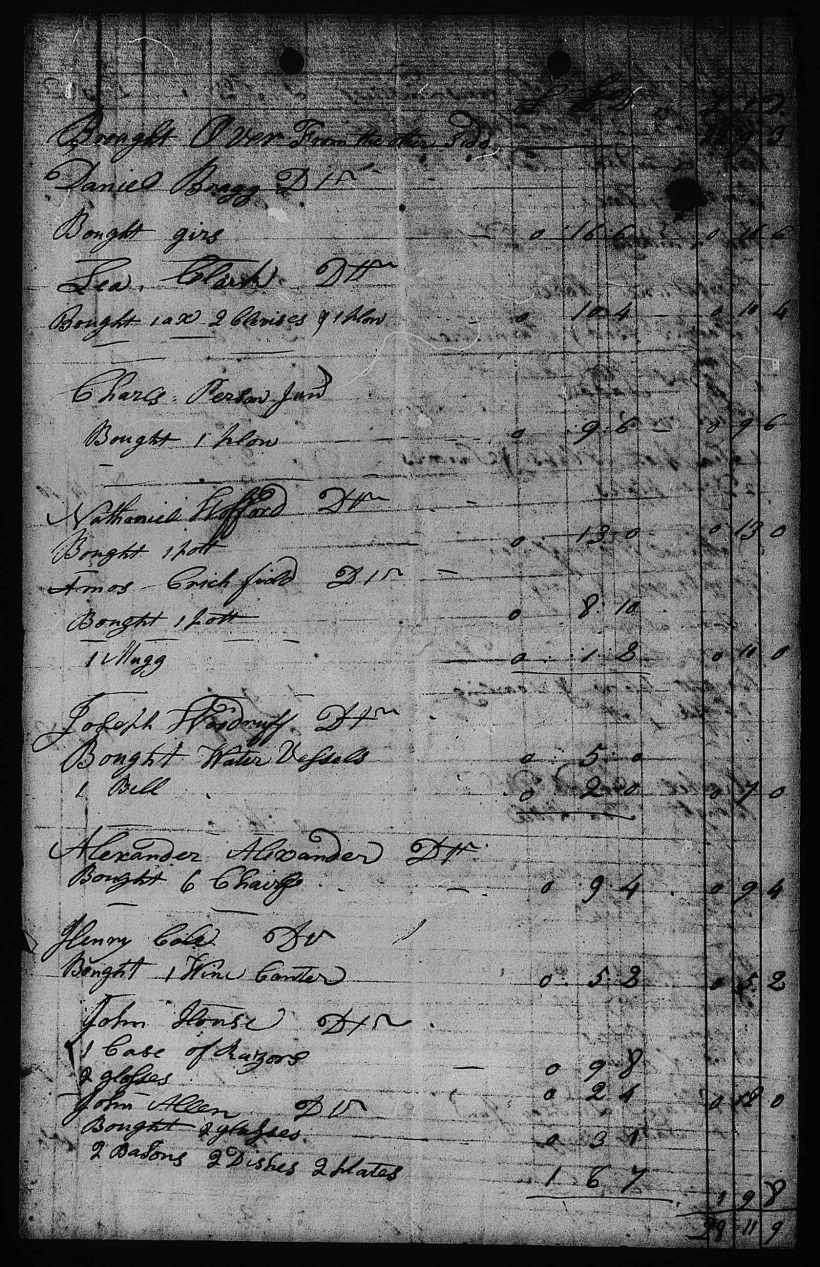

- The next document in the file is an account of a sale of the appraised property held 12 February 1795, and returned to court on 19 February.

Mark Lindsey (1 mare); Mary Lindsey (1 mare, 1 featherbed and furniture, 1 wheel, 1 women’s saddle, 1 dutch oven, a teapot, 3 cups, saucers, ½ dozen plates); Nathaniel Woodruff Sr. (1 cow and calf); George Bruton (1 cow and yearling, 1 coffee pot); Rachel Arnold (1 tea kettle); John Peice (1 reel); James Bruton (1 saddle, ½ dozen plates, a lot of pewter); Wm. Lindsey Jr. (a pair of saddle bags); James Allen (2 wheels); Daniel Bragg (gears); Lea Clark (1 ax, 2 clevises, 1 plow); Charles Person (1 plow); Nathaniel Wofford (1 pot); Amos Crichfield (1 pot, 1 mug); Joseph Woodruff (water vessels, 1 bell); Alexander Alexander (6 chairs); Henry Cole (1 wine canter); John Hanse (i.e., Hance) (1 case of razors, 2 glasses); John Allen (2 glasses, 2 basins, 2 dishes, 2 plates), William Lindsey Sr. (teapot, 6 cups and saucers); Holloway (Joyner?), (a set of knives and forks, 2 locks); Samuel Woodruff Jr. (5 old knives, 3 old forks, corkscrew); Nathaniel Woodruff Jr. (1 table, wearing clothes); Samuel Woodruff Sr. (2 books); John Sims (1 trunk); Thomas Holden (2 old blankets and bed cover); William Wofford (3 rawhides); Moses Snow (1 cutting knife and curry comb); Isaac Crow (plank); Adam Young (7 barrels of corn), for a total of £34 pounds 3s 9d.

There’s much to note here. First, note that Mark and Mary Lindsey lead the list of buyers, as if they were buying in concert with each other. It was not uncommon at estate sales in this period for other buyers to allow the closest family members to have first choice of property. If Mark is, as I suspect he is, a son of Dennis by a wife prior to Mary (and is close in Mary to age), then it would make sense that one of Dennis’s sons, perhaps the oldest of his sons, and his widow would be the first purchasers of his estate.

Note, too, that the only people with the Lindsey surname buying at the sale are Mark and the widow Mary, and William Lindsey Sr. and Jr. This tends to confirm my conclusion that William Sr. may have had sons Dennis and William Jr.

The two books that Samuel Woodruff bought would seem to be the testament/bible and hymn book listed in the estate inventory. This Samuel could either be Samuel (1763-1836), the son of Nathaniel Woodruff, or that Samuel’s nephew Samuel Woodruff (1766 – abt. 1840), son of Nathaniel Woodruff Jr. This younger Samuel Woodruff married Mary Dinsmore, sister of Mary Jane Dinsmore who married Mark Lindsey. If the bible Samuel Woodruff bought at this estate sale was a family bible — and in this period, bibles were normally used to record dates of birth, marriage, and death of family members — it’s interesting that a family bible may have been sold outside the family of Dennis Lindsey.

Who is Rachel Arnold, who buys a tea kettle at the sale? As I’ve previously noted, an Arnold family had dealings with the Tate family in Spartanburg County who lived near the Lindseys, into which the Isaac Lindsey who may have been a son of Dennis married. Since we know that the wife of William Lindsey Sr. was named Rachel, it occurs to me, of course, that there may be daughters of William Sr. or of his sons whom we have not yet discovered, who may have had the given name Rachel — though I have absolutely no evidence to allow me to conclude that Rachel Arnold was née Lindsey.

Other names: we’ve met these Woodruff men in numerous other documents involving the Lindsey family. Their appearance at the estate sale reminds us that they were close neighbors of William and Dennis Lindsey, and that the Woodruffs and Lindseys connected in various other ways (e.g., Dennis Lindsey’s son Dennis would marry Anna, daughter of Joseph Woodruff and Anna Lindsey). We know George Bruton, too, another neighbor and substantial landowner, to whom half of Dennis’s 248-acre grant would go, and whom Mark Lindsey would follow to Wayne County, Kentucky. The James Bruton in the sale account is George’s brother. The Woffords are also familiar to us, having appeared in records of this family from the time it first arrived in South Carolina by 1768.

I think that the John and James Allen of the sale document are father and son. The father John Allen married Elizabeth Lindsey, sister to Anna Lindsey who married Joseph Woodruff. John and Elizabeth Allen’s son James married Mary, daughter of Joseph and Anna Woodruff. James’s brother William Lindsey Allen would marry Dennis Lindsey’s widow Mary by April 1796.

Alexander Alexander is buried in the old Bethel cemetery at Woodruff with his tombstone stating that he was born in Belfast in 1753 and came to South Carolina in 1778.[6] He was a Revolutionary soldier, as a monument to Revolutionary soldiers buried in this cemetery indicates.[7] Alexander married Anna, daughter of John McCrory of Jamey’s Creek.[8] Anna McCrory was a sister of Margaret McCrory who married Henry Earnest. They were the parents of Rachel Earnest who married William Lindsey (1760/1770 – 1840), son of William Lindsey Sr. Henry appears as a Loyalist of Ninety-Six district in a 1776 statement of John Rutledge, who represented South Carolina in the First Continental Congress.[9] It’s also worth noting that Alexander Alexander received George Bruton’s pay indent for service in Roebuck’s Spartan Militia, according to a July 1786 receipt in the South Carolina Revolutionary audited account file of Bruton.[10] Finally, note that Alexander Alexander had a son John Alexander who served as a U.S. representative from Ohio from 1813-1817.[11]

The Henry Cole who bought Dennis Lindsey’s wine “canter” is yet another Revolutionary soldier buried in the old Bethel cemetery at Woodruff. His Revolutionary pension application, filed in Spartanburg District 15 February 1819, has an affidavit dated the same day by George Roebuck affirming Cole’s Revolutionary service.

- Also found in Dennis Lindsey’s estate file is a 9 April 1796 list of accounts against the estate, showing the estate owing George Gordon, Joseph Woodruff, Andrew Thompson, Alexander Morrison, William Gist, Thomas Price, John Young, Jacob Pennington (for 1 good coat of cloth); and Nathaniel Woodruff (for 1200 weight of good tobacco).

Andrew Thompson is, I think, the Andrew Thomson who surveyed Dennis Lindsey’s 248-acre tract in 1792. Jacob Pennington is perhaps the son of the Jacob Pennington (1716-1774) to whom William and Rachel Lindsey sold William’s original 1768 land grant on the Enoree in 1772. John Young may well be the John Young who served with Nicholas Holley (whose name also appears in these estate records owing a debt to the estate) in Captain Zachariah Gibbs’ Loyalist Spartan militia during the Revolution.[12] The Adam Young who was a buyer at the estate sale is, I think, a relative of John and also connected to Nicholas Holley.

- Dennis Lindsey’s estate file also has an 11 April 1796 account of money received by the estate, listing those who had paid the estate as Nathaniel Woodruff, Sr., George Bruton, Rachel Arnold, James Bruton, William Lindsey Jr., James Allen, Daniel Bragg, Lea Clark, Charles Person, Nathaniel Wofford, Amos Crichfield, Joseph Woodruff, Alexander Alexander, Henry Cole, John Hanse, Samuel Woodruff III, John Sims, William Wofford, and Adam Young, for a total of £20 18s 5d. Appended to this list is a statement that the estate had received from book accounts payments by Carlton Lindsey, Lenoah Westmoreland, William Westmoreland, and Mark Lindsey for a total amount of £21 pounds 6s 4d.

Those paying the estate were, it can be seen at a glance, buyers at the estate sale, so these are people who had evidently paid the estate by April 1796 for what they purchased at the sale. Several names in the book accounts are of interest. The Carlton Lindsey listed in this set of accounts is, in my view, a brother of Anna Lindsey who married Joseph Woodruff and Elizabeth Lindsey who married John Allen. As I have stated previously, these Lindseys are not related to the Lindsey family from which William and Dennis Lindsey come; their family came down to Spartanburg County from Rutherford County, North Carolina, and is closely connected to the Woodruffs and Allens for generations.

We met William Westmoreland in a previous posting when we noted that William Lindsey Jr. sold Spencer Bobo 200 acres in March 1817, which seems to have been the land on which his father William Lindsey lived after William sold his 300-acre grant on the Enoree. Then in July 1818, Bobo’s widow Jane Farrow Bobo sold 600 acres on Ferguson’s Creek with the deed stating that land joined, among others, David, John, and James Bruton, William Westmoreland, and Josiah and Nathaniel Woodruff.

The Lenoah Westmoreland named in the estate’s book accounts, who is a brother of William, married Elizabeth, daughter of John Tate.[13] Elizabeth’s sister Mary married the Isaac Lindsey who is, I believe, the Isaac Lindsey who witnessed Dennis Lindsey’s 1792 bond to George Bruton, and who may well have been a son of Dennis Lindsey.

- Finally, Dennis Lindsey’s estate file has a 14 September 1796 list of payments made by the estate to the following persons: William Wells for being with Dennis Lindsey as he died; the county “clark”; Alexander Alexander; William Flippen; Joseph Woodruff; Alexander Cameron; Nathaniel Woodruff; Samuel Farrow; and Nicholas Holley, for a total of £40 1s 8d. With this is also a list of debts due to the estate, with the following names: John Dentana; John Poore; Nicholas Holley; John Mullen; George Humphreys; Charles Duet; Charles McHaffe. The list notes that there are a number of small notes and accounts due from persons who had moved to parts unknown or who had been declared insolvent, and that the widow Mary, now Mary Allen, expects that these will not be recovered, except the note on Dentana, which was in suit. This is signed by Mary Allen, who is now signing without using a mark, and was returned to court on 17 January 1797.

William Wells represented Spartanburg District in the state legislature from 1796-1800.[14] Nicholas Holley is the man discussed above, linked to the Young family. Nicholas Holley served in Zachariah Gibbs’ Loyalist Spartan militia along with John Young. We met Nicholas Holley in a previous posting noting that William Lindsey gave security in a March 1787 suit of Ephraim Reece against Nicholas Holley. On 20 October 1791, Nicholas Holley sold George Roebuck 200 acres on Jamey’s Creek that Roebuck then sold in November of the same year to Sampson Bobo, father of Spencer Bobo mentioned above.[15]

Well, that’s Dennis Lindsey’s estate file and what I glean from it. Perhaps those of you reading this posting will spot things I am missing. We learn from Spartanburg county court minutes for 18 January 1797 that Alexander Alexander sued Mary, Dennis’s widow, as the assignee of Joseph Jordan, Esquire, in a case of debt.[16] I don’t have information about the outcome of that lawsuit.

As I’ve stated a number of times, we know from Spartanburg County court records that Dennis and his wife Mary had a son Dennis, who was, as we’ll see in a subsequent posting, placed under the guardianship of his step-father William Lindsey Allen in 1802. This is the only definitively proven child of Dennis Lindsey. I’ve noted that I’m fairly confident that the Mark Lindsey who was a buyer at Dennis’s estate sale was also a son of Dennis, though not by wife Mary (and I’ll say more about Mary when I discuss the son she had by Dennis, Dennis Jr.). I also think, but have less certainty about this, that an Isaac Lindsey who moved to St. Helena Parish, Louisiana, prior to 1812 is probably another son of Dennis, and am inclined to think that a John Lindsey who ended up in Lawrence County, Alabama, where Mark settled, may be another son.

In my next set of postings, I’ll discuss each of these men and their families, and explain why I think the last three may be sons of Dennis.

[1] Loose-papers estate file of Dennis Lindsey, Spartanburg County, South Carolina, Probate Court, estate file 1111.

[2] Robert Stansbury Lambert, South Carolina Loyalists in the American Revolution (Columbia: Univ. of South Carolina Press, 1987), pp. 183, 300.

[3] C.L. Bragg, “Pragmatism and Principle: Capt. Alexander Chesney and the Revolutionary War in South Carolina,” in The Consequences of Loyalism: Essays in Honor of Robert M. Calhoon, ed. Rebecca Brannon and Joseph S. Moore (Columbia: Univ. of SC Press, 2019), p. 91.

[4] Brent H. Holcomb’s transcription of the county court minutes for 12 January 1795 show Mary being made administratrix, and George Bruton, William Moore, and John Woodruff being appointed to appraise the estate, on that date: see Spartanburg County, South Carolina, Minutes of County Court 1785-1799 (Easley: Southern Hist. Press, 1980). The LDS Family History Library does not have microfilm copies of Spartanburg County court minutes for this period.

[5] On 24 October 1847, Samuel Asbury Lindsey, a son of Dennis Lindsey (1794-1836) and Jane Brooks of Lawrence County, Alabama, would write his sister Martha from National Bridge in Mexico during the Mexican War, and would say, after he had used the phrase “dam’ fool” to describe himself, “Excuse me for using vain language, though I read the Testament as much as any of you do.” Dennis (1794-1836) was a son of Mark Lindsey and Mary Jane Dinsmore, and therefore a grandson of Dennis (abt. 1755-1795), if I am correct about Mark’s parentage. Samuel Asbury Lindsey’s letter is transcribed in Henry Carlton Lindsey, Mark Lindsey Heritage, 1740-1982 (priv. publ., Brownwood, TX, 1982), pp. 117-8. I am not sure of the present whereabouts and owner of the letter.

[6] See a photo of the tombstone at his Find a Grave memorial page maintained by Mary Alexander Heaven, who took the tombstone photo.

[7] See a photo of the monument by The Dash at ibid.

[8] See loose-papers estate file of John McCrory, Spartanburg County, South Carolina, Probate Court, file 1434. John’s will, dated 12 April 1787, proved April 1791, names Anna Alexander as his daughter.

[9] See Lori Olson White, “The Loyalist Hamby Boys,” at The Buttermaker and the Midwife, 6 July 2015, transcribing a list compiled by John Rutledge of men convicted of sedition by Ninety-Six District court on 15 November 1776, including Henry Ernest [sic]. Also in the list is Isaac Hamby, whom we’ve met in a previous posting, and Robert Alexander, who gave an affidavit on behalf of David Dinsmore’s Loyalist land claim in Nova Scotia in 1786, and who may well have been, I think, a relative of Alexander Alexander. White states that the original documents in the South Carolina Archives.

[10] Will Graves’ transcription of George Bruton’s Revolutionary pension application (S30891) at Southern Campaign Revolutionary Pension Statements & Rosters includes a transcription of the receipt, noting that it’s from Bruton’s South Carolina Revolutionary audited account file.

[11] See John Alexander’s Wikipedia biography and his biography in Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

[12] See J.D. Lewis, “The Known Provincials & Loyalists at the Battle of Kings Mountain October 7, 1780,” at the Carolana website.

[13] See John Hawkins Napier, The Tates of Pearl River (1999).

[14] See J.B.O. Landrum, History of Spartanburg County (Atlanta: Franklin, 1900), p. 648.

[15] Spartanburg County, South Carolina, Deed Bk. G, pp. 94-98.

[16] Holcomb, Spartanburg County, South Carolina, Minutes of County Court, pp. 236-7.

2 thoughts on “The Children of William Lindsey (abt. 1733-abt. 1806): Dennis Lindsey (abt. 1755-1795) (4)”