To prepare for my trip to Clare and Limerick, parts of Ireland in which I haven’t previously spent time and which I want to see primarily because I know I have a familial connection to them going back quite a way in time, I’ve compiled some research notes to guide me as I dig for information. These notes point to solid documented information about Dennis Linchy’s Irish connection, and then to some clues that may, I hope, help those of us trying to find out more about Dennis’ Irish roots to discover some new information.

Though the chances that I’ll find some new documents are slim when few documents are extant to provide information about people emigrating from Ireland in the early 1700s and we don’t even know where Dennis was born, lived, and indentured himself in Ireland as he left for Virginia, I keep hope alive that something unexpected may turn up if I place myself in the right spot. I’m, after all, yet another Dennis Lindsey in a very long line of men in my family who have inherited that given name from our immigrant forebear Dennis Linchy (his surname shifted to Lindsey after he finished his indenture in Virginia and then went to North Carolina), and perhaps that fact alone will bring me a bit of luck.

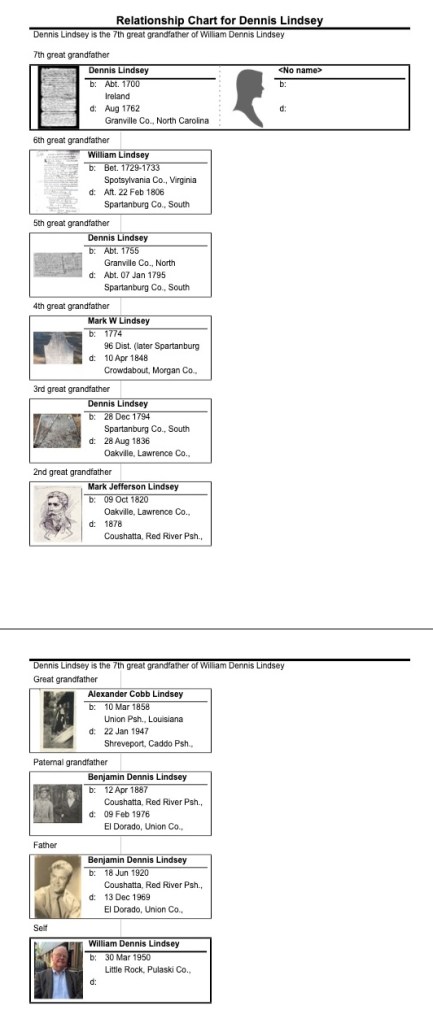

As a first-born son, I was given the names William and Dennis after my grandfathers William Z. Simpson and Benjamin Dennis Lindsey. My father was a Benjamin Dennis Jr. My grandfather was named for an uncle Benjamin Dennis Lindsey, who was, in turn named for his grandfathers Benjamin Harrison (1794-1835) and Dennis Lindsey (1794-1836). That Dennis was named for his grandfather Dennis Lindsey (abt. 1755-1795), who was named for his grandfather Dennis Linchy the Irish immigrant.

What follows are the research notes I’ve compiled as I prepare for my trip to Ireland and my time in Limerick and Clare — and at the National Library in Dublin:

Here are solid, documented facts about Dennis Linchy and his Irish connection:

1. Dennis came to Virginia from Ireland and was, we can fairly confidently conclude, born in Ireland.

- On 4 June 1718, court minutes in Richmond County, Virginia, state that Francis Collett, master of a ship that had brought four indentured servant boys to Virginia, had been summoned to court to declare his knowledge of their indentures.[1]

- On 6 August 1718, Richmond court minutes state that William Welch, Michael Whaley, Thomas Grady, and Dennis Linchey had been brought to Virginia aboard a ship piloted by Francis Collett and had indentured themselves at an unspecified indenture office in Ireland.[2]

2. Dennis was likely born around or not long after 1700.

- Richmond County, Virginia, court minutes on 4 June 1718 (see 1a) refer to the four indentured servants Francis Collett brought from Ireland to Virginia as “servant boys.”

- Most indentured servants brought to Virginia in the colonial period were at least 18 years old, and many were younger.[3]

- Court minutes on 6 August 1718 (1b above) state that the court wanted to determine the age of the four servants. Length of servitude for indentured servants depended on age.

- In March 1654/5, Virginia’s General Assembly legislated that all Irish servants who had been serving in Virginia from September 1653 who had been brought to the colony without indenture papers were to serve six years, if they were above 16 years at time of import, and were not to serve an indenture beyond their 24th year.[4]

- Immediately following the summons of Francis Collett to court on 4 June 1718 in Richmond court minutes (see 1a above), court minutes say that John Peattersby, servant to Patrick Dunn, had been presented in court and his age was proven to be 13. At the next court session on 2 July,[5] court minutes state that Daniel Tommins, servant to William Hanks, had been brought to court for inspection and his age was judged to be 13 years, and Cornelius Shearton, servant to Aaron Brannon, was brought to court for inspection and judged to be 14 years old.

3. It can be documented from a number of sources that the ship piloted by Francis Collett on which Dennis Linchy arrived in Virginia in 1718 was The Expectation, and that it sailed from Bristol in January 1718 with servants from the English West Country and Wales and then stopped in Ireland to pick up servants there.[6]

- Richmond County court minutes for 6 August 1718 (see 1b above) state that Samuel Skinker handled the sale of the Irish servant boys to masters in Virginia.

- Samuel Skinker was a merchant of Bristol, England, living in 1718 in the part of Richmond County that would soon King George County, Virginia.[7] He was preceded by another Bristol merchant living in Virginia, Benjamin Deverell, who died in 1717. The Bristol firm these men represented, Bristol Company of Merchants, sold items like paper, pipes, textiles, salt, nails, rum, and spices, in addition to servants, to Virginia residents, and brought Virginia commodities like tobacco back for sale in Britain.[8]

- Connected to Skinker and the Bristol firm of merchants was John Becher, a wealthy merchant born in County Cork, Ireland, who was sheriff of Bristol in 1713 and mayor in 1721, and who founded a slave-trading firm selling enslaved persons to the colonies.

4. Though we know from Richmond County, Virginia, court minutes that the four servant boys Collett brought to Virginia indentured themselves at an indenture office in Ireland — evidently together — court minutes do not specify the place at which they indentured themselves or where Collett picked them up to bring them to Virginia.

- Servants were frequently indentured before the mayor of the port of embarkation, with the indenture made to a merchant or the ship’s captain.[9]

- When they arrived in the colonies, their indenture would be sold in an American port and registered officially there.[10]

- Most indentured servants arrived in the colonies in spring and early summer.[11]

- The market for Irish servants was brisk in the colonies due to a limited labor pool, with Dublin, Waterford, Cork, Youghall, and Limerick contributing significantly to this market in the early part of the 1700s.[12]

- “Large numbers [of indentured servants] departed Ireland through Cork and Limerick in peak emigration years, many of them bound for the southern colonies of the American mainland and the West Indies.”[13]

The preceding list summarizes what we know from sound documentation about the Irish connection of Dennis Linchy, who came from Ireland to Virginia as a young Irish indentured servant in 1718:

- He came to Virginia from Ireland.

- He was young (a “servant boy”) in 1718.

- Putting a and b together: It’s almost certain he was born in Ireland, probably around or not long after 1700.

- He arrived with three other Irish servant boys, all of whom indentured themselves at an unnamed office in Ireland.

- The first American record we have stating his name calls him Dennis Linchey. A 5 January 1721 record in King George County, Virginia, formed in 1720 from Richmond County, calls him Denis Linchy. It’s likely the four Irish servant boys arriving in Virginia in 1718 spoke Irish as their first language; when Francis Collett failed to appear in court, the court summoned three Irish men to meet with the four boys and get information about their indentures. This record suggests to me that the four boys likely spoke Irish as their first language.

- Dennis Linchy’s surname in Irish would have been Ó Loingsigh. Linchy is more or less a phonetic rendering of how this Irish name is pronounced. Ó Loingsigh is the Irish name of Lynch families, who also have sometimes used the forms Linchy or Linchey for their surname. Dennis Linchy’s surname morphed to Lindsey in Virginia and North Carolina records following his release from his indenture. Colonial Virginia records show a number of people who had the surname Lynch or Linchy when they arrived in Virginia, whose name then shifted to Lindsay or Lindsey.

Note that none of the records I’ve cited tell us where Dennis Linchy was born in Ireland, where he was living when he left Ireland as an indentured servant, or where he indentured himself and then shipped to Virginia aboard The Expectation.

The most likely way to find this information is to find the indenture office (or mayoral office) at which the four servant boys indentured themselves before leaving Ireland in January 1718 (again: I am assuming these boys indentured themselves as a group, together, and that they likely lived close to each other). Very few records of this sort, records from indenture or mayoral offices, appear to be extant in Ireland. In one colonial court record in Richmond County, Virginia, I find an Irish indentured servant, Patrick Jorn of the Rower, stating on 19 October 1705 that he indentured himself at an office in New Ross in County Wexford with Samuel Pitt acting as recorder of the indenture.[14]

Another possibility I’ve explored is to see if more records of the shipping of The Expectation to Virginia in January 1718 from Bristol exist in the British Public Records Office or the Bristol archives. I have not been able to track any such records.

In the absence of concrete information about where Dennis Linchy was born, grew up, and indentured himself in Ireland, the search for a specific place that might hold his indenture record is a stab in the dark. There are some clues, however, that may assist us in figuring out where to search. One of these involves very sound documentation. This is the Irish Type III DNA profile of known male descendants of Dennis Linchy.

Some Irish Clues about Dennis Linchy’s Irish Connection

The DNA evidence:

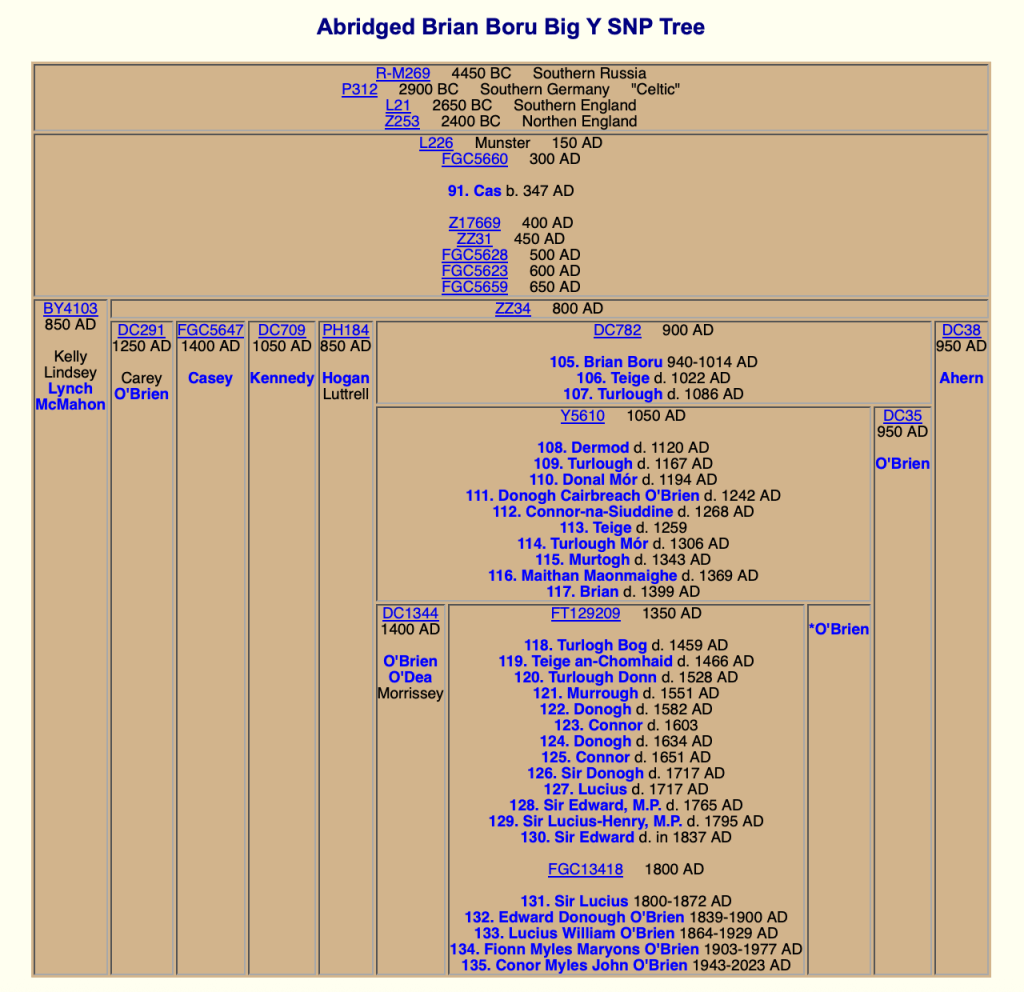

Known male descendants of Dennis Linchy (I’m one of these) have the Irish Type III DNA profile.[15] A number of us (again, I’m included) have done the Big Y DNA test with Family Tree DNA (FTDNA). FTDNA reports to us that our haplogroup is R-DC908, a haplogroup that branched from the R-FT77683 haplogroup about 1200 CE.[16] FTDNA estimates that the ancestor shared by the group of us claiming Dennis Linchy as our immigrant ancestor was born about 1700 CE. Note that this is just what I myself have deduced from the records I cite above suggesting his probable age when he arrived in Virginia.

FTDNA also reports that the country in which the R-DC908 is most frequently found today is Ireland, with less than 1% of the Irish population exhibiting this genetic haplogroup.[17] The R-DC908 haplogroup is, that is to say, rare and is found among a specific subset of the Irish population, families who claim historic roots of kinship to the Irish High King Brian Boru, the so-called Dalcassian families.[18]

This haplogroup is concentrated in the area in western Ireland in which Brian Boru and these families lived, in County Clare and the nearby counties of Limerick and Tipperary. According to FTDNA, Brian Boru and I share an ancestor about 650 CE.[19] FTDNA’s report about this states that this is a rare connection: “1 in 2,500. Only 283 customers are this closely related to Brian Boru.”[20] As the International Society of Genetic Genealogy Wiki page for Irish Type III states,

In February 2006, In response to a question on the GENEALOGY-DNA@rootsweb.com email list, Dr Ken Nordtvedt identified a small R1b cluster that he had found was centred on the counties of Clare, Limerick and Tipperary in Ireland.”[21]

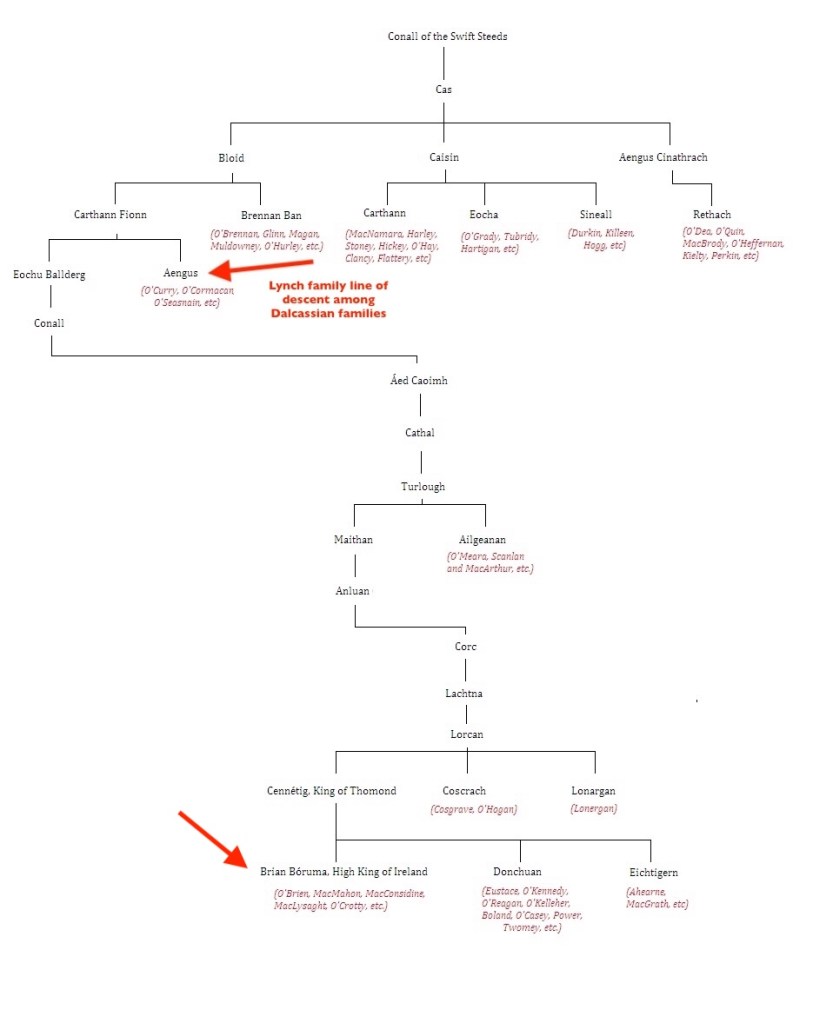

Lynch is not an uncommon Irish surname. But not all Lynch families track back to the same roots. The DNA profile of men who can prove descent from Dennis Linchy provides solid evidence that the Lynch (Linchy) family from which we descend is the Dalcassian Lynch family discussed by John O’Hart in his Irish Pedigrees; or the Origin and Stem of the Irish Nation. O’Hart states,[22]

The O’Lynch family derives its origin from Aongus, the second son of Carthan Fionn Oge Mór, who is No. 93 on the “O’Brien Kings of Thomond” pedigree.

And:[23]

AONGUS, a brother of Eochaidh Balldearg who is No. 94 on the “O’Brien” (Princes of Thomond) pedigree, was the ancestor of this branch of that family. The family derives its name from Longseach (“longseach:” Irish, a mariner), a descendant of that Aongus; and were after him called O’Loingsigh, or, anglicé, O’Lynch, and Lynch. It would appear that the “O’Lynches’ Country” was that portion of territory lying around Castleconnell, in the barony of Owny and Ara, with portion of the lands comprised in the county of the City of Limerick.

As Peter Biggins notes, the Thomond O’Lynch family is closely related to other families of the kingdom of Thomond long ruled by Brian Boru’s descendants, the O’Briens.[24] These families include the O’Briens themselves, the Kennedys, and the McMahons, all surnames found to be the first matches to the Y-DNA of men descending from Dennis Linchy after our matches to each other have been noted as our strongest matches. Peter Biggins notes that a family with the surname spelling Lindsey (i.e., the family descending from Dennis Linchy) is among the Dalcassian families with historic kinship connections to Brian Boru.[25] Brian’s father was Cennétig mac Lorcáin, the source of the Dalcassian Kennedy surname,[26] and Brian’s brother was Mathgamain mac Cennétig, the source of the Dalcassian Mahon surname.[27]

The Wikipedia entries for both the Dalcassians and Cennétig mac Lorcáin provide a helpful chart entitled “Tree graph showing relationships between the Dalcassian septs.” This flow chart is based on O’Hart’s Irish Pedigrees charting the lines of descent of the various Dalcassian families and their bloodline connections to each other.[28]

Some other (inconclusive) clues:

The Y-DNA profile of men descended from Dennis Linchy does not, of course, tell us where Dennis himself was born, grew up, indentured himself, and then left Ireland. It only tells us that quite a way back in time to the medieval period, at least, Dennis’ family roots lay in the Dalcassian families of western Ireland, where Brian Boru was born (in Clare) around 940 CE.

To say that this DNA evidence yields further evidence about where Dennis Linchy was born and lived is to take a big leap. Over hundreds of years — e.g., from 1000 to 1700 — families can be peripatetic. A family with roots in Clare might well have had branches that had migrated to, say, Cork during such a long time frame.

Still, in the absence of any information at all about where Dennis Linchy was born and lived, and given the solid evidence that DNA provides us that he had familial roots in the kingdom of Thomond (Clare, Limerick, Tipperary) running back in time, it’s worth entertaining the possibility that Dennis’ Linchy family had remained close to its geographic roots up to 1700 or so, and that Dennis was born in the old kingdom of Thomond where his Dalcassian Lynch family once had a strong foothold. Many Irish families have lived for long centuries in the very same place in which they have been rooted from time immemorial.

I mentioned early on (see 1b above) that Richmond County, Virginia, court minutes tell us the names of the other three servant boys who arrived in Ireland with Dennis: they were William Welch, Michael Whaley, and Thomas Grady. If these four servant boys indentured themselves in Ireland as a group, it’s possible they lived near each other. Do these surnames provide any possible clues?

The first thing to note about the four names is that Grady/O’Grady is yet another Dalcassian surname. Historically, the Gradys or O’Gradys have been particularly concentrated in County Clare. It’s worth asking whether Dennis Linchy and Thomas Grady, both with surnames found among the Dalcassian families, and in Dennis’ case given DNA evidence from his descendants, with Dalcassian ancestry, shared some Dalcassian kinship and may both have had roots in County Clare.

When I look for these surnames in Clare on the Tithe Applotment survey taken about a hundred years after the servant boys arrived in Virginia, I find, interestingly enough, that both a Grady and a Linchy family were living in Clondagad civil parish in Clare, some 25 miles west of Limerick across the Shannon. Living in Bunratty parish on the Limerick side of the Shannon and not far from Limerick when the Tithe Applotment survey was taken are Welch families, another of the surnames of the four servant boys who came to Virginia from Ireland in 1718. The only non-Clare surname in the group is Whaley, a name found just to the north of the places I’ve mentioned, in County Galway.

A possibility to think about, then? — four Irish servant boys with Clare roots went to Limerick in late 1717 or early 1718 and indentured themselves as a group to sail to Virginia. I have no proof of this, but it’s a hypothesis worth entertaining, in light of the DNA evidence we have about Dennis Linchy’s roots.

If this is what happened in the case of the four Irish servants indentured in Virginia in 1718, then, unfortunately, as far as I’ve been able to determine, no records exist for either an indenture office or for the mayoral office in Limerick in 1717-8. Or if records do exist for the latter, they do not include indenture documents. William Medcalf was Limerick’s mayor in 1717, and in 1718, the mayor was George Bridgeman. I’ve contacted the Limerick archives and they have no records of the sort I’m seeking. I’ve searched for possible archival records at the National Library of Ireland using NLI’s online catalogue and Richard Hayes’ History of Irish Civilization, and I’ve drawn a blank.

An even more tenuous clue: among the holdings of the Clare County Library is a set of transcriptions of gravestones from the graveyard of Killone Abbey just south of Clare’s county seat, Ennis.[29] The transcription shows the following tombstone in the Killone Abbey graveyard:

Here lies the Body of | Denis Linchy who Depard | this life the ?? the ??th | 1773 Aged ?? years Erect | ed by his son Denis Linchy | Amen.

And next to this tombstone for Denis Linchy is a stone stating,

Here lies the body of | Denis Lynch | Who departed this life | Feb 23rd 1789 | Aged 16 years | Erected by his Father | Denis | Requiescant in pace

The ruined Killone Abbey is about 23 miles west of Limerick and 2.5 miles south of Ennis, the county seat of Clare.[30] Killone Abbey is on the grounds of Newhall Estate, which originally belonged to the O’Brien family, to Murrough O’Brien, 1st Earl of Thomond.[31] The O’Briens founded Killone Abbey, a monastery for Augustinian nuns, in the 12th century.

Killone civil parish, in which Killone Abbey is found, borders Clondagad parish, where I find Linchys and Welches living in the early 1800s when the Tithe Applotment records were made. Killone joins Clondagad on the north. The Tithe Applotment records show one Lynch, the Widow Lynch, living in Killone parish, Lackanascagh townland, in April 1828 when this record was made. This townland is just a tiny bit east of Newhall, where Killone Abbey is located.

Note this portion of a map (below) of historic Irish family names found in a set of notes entitled “Learned Families of Thomond” at the website of County Clare Library.[32] The website credits Edward MacLysaght’s Irish Families for this map.[33] Note the O’Lynch family name on the right-hand side of the map just northeast of Limerick. This is the original stronghold of the Lynches of Thomond, the Dalcassian Lynches. The map also shows just across the Shannon a territory marked by MacLysaght as inhabited by a branch of this family that he calls the O’Linchys or Lynches. This is in the vicinity of the parish of Clondagad in which Linchys and Gradys are found in the Tithe Applotment books.

In conclusion, what might a visit to archives and libraries in Limerick, Ennis, the county seat of Clare, and Dublin yield for those of us seeking information about the roots of our immigrant ancestor Dennis Linchy? Realistically, given that we have no positive information about where in Ireland he was born, grew up, and indentured himself, it’s unlikely that records about him will turn up. We don’t know for certain that he grew up in Clare or Limerick, or that he indentured himself in Limerick. The hypothesis that he did so is a stab in the dark based primarily on sound information that his roots lie among the Dalcassian families, and on other pieces of information discussed above that, placed together, suggest this scenario as a certain possibility.

Since no records of an indenture office in Limerick or mayoral records from the requisite time frame appear to exist, it’s unlikely a researcher visiting libraries and archives there will find indenture information about Dennis Linchy in Limerick. The likeliest place to find such records might well be the National Library of Ireland, but thus far, my attempts to locate material at NLI via its catalogue and Hayes’ History of Irish Civilization have drawn a blank.

On the other hand, one never knows…. A visit to Limerick and Clare certainly places one right in the territory in which Dennis Linchy’s long ancestral roots lie, so a visit to that part of Ireland is enticing for anyone interested in Dennis’ ancestry. And when one takes the leap and travels to an unknown place with hope to find some long-sought piece of information, sometimes luck happens — sometimes you meet someone who has an unexpected piece of information, an unexpectedly helpful archivist or librarian, and pieces begin to fall into place…. One lives in hope!

[1] Richmond County, Virginia, Court Order Bk. 8, p. 20.

[2] Ibid., p. 27.

[3] Carol McGinnis, Virginia Genealogy: Sources & Resources (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1993), p. 12.

[4] William Waller Hening, The Statutes at Large: Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia, from the First Session of the Legislature, in the Year 1619, etc., vol. 1 (New York: Bartow, 1819), p. 411, act 6.

[5] Richmond County, Virginia, Court Order Bk. 8, p. 21.

[6] Peter Wilson Coldham, The Complete Book of Emigrants 1700-1750 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1992), p. 209, abstracting Bristol port books, E/190/1454/8 in the Public Records Office. Coldham’s abstract of the Bristol port book record in the PRO showing The Expectation sailing from Bristol to Virginia in January 1718 states that the voyage was financed by Richyate Coole & Co. of Bristol. Coldham shows Coole’s company (his name also appears as Richyeat Coole) financing voyages from Bristol to Virginia from October 1707 to December 1720. On Richyate Coole as a Bristol merchant engaged in mercantile enterprises in Virginia, see Westmoreland County, Virginia, Court Order Book 1731-1739, p. 20f. See also Virginia Colonial Records Project, survey report 11138, listing PRO records with information about tobacco shipped from Virginia to Britain and Europe in 1719/20, including one shipment brought by The Expectation as it left Virginia on 15 December 1720: Exchequer King’s Remembrancer, Port Books, Exeter, Customer Public Record Office Class E 190/993/7.

[7] On Bristol as the point from which a significant percentage of English servants — drawn largely from the West Country — shipped to Virginia, see David Hackett Fischer, Albion’s Seed (New York and Oxford: Oxford UP, 1989), pp. 236-240.

[8] Thomas K. Skinker, Samuel Skinker and His Descendants (St. Louis, 1923); Brian Townes, National Register of Historic Places Registration Form for Millbank, King George County, Virginia, online at website of Virginia Department of Historic Places; Essex County, Virginia, Will Bk 1714-1717, p. 351; Richmond County, Virginia, Miscellaneous Records 1699-1724, pp. 95B, 112A, p. 329; and King George County, Virginia, Deed Bk. 2, pp. 41-42.

[9] Richard K. MacMaster, Scotch-Irish Merchants in Colonial America (Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation, 2009), pp. 29-30.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid., p. 30.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Thomas M. Truxed, Irish-American Trade, 1660-1783 (Cambridge, Cambridge UP, 1988), p. 137.

[14] Richmond County, Virginia, Court Order Bk. 4, p. 38.

[15] On the Irish Type III genetic profile and its historic origins among the Dalcassian families of western Ireland, see Dennis Wright’s The Irish Type III Website. I had no idea that I had this genetic profile until Dennis Wright saw my Y-DNA results reported someplace online and contacted me to tell me that I and other men descended from Dennis Linchy who have had Y-DNA tests are Irish Type III.

[16] FTDNA, “Your Haplogroup Story: R-DC908.”

[17] FTDNA, “Country Frequency.”

[18] “Brian Boru,” “Dalcassians,” both at Wikipedia. See also “Brian Boru (c. 940-1014),” at the County Clare Library website.

[19] FTDNA, “Notable Connections.”

[20] Ibid.

[21] ISOGG Wiki, “Irish Type III.”

[22] John O’Hart, Irish Pedigrees; or the Origin and Stem of the Irish Nation, vol. 1 (Dublin, J. Duffy and Co.; New York, Benziger Brothers, 1892), pp. 101-2.

[23] Ibid., p. 233.

[24] Peter Biggins, “DC782 Brian Boru,” at PetersPioneers. On the kingdom of Thomond, its history and geographical extent, see “Thomond,” Wikipedia. On the O’Brien dynasty ruling Thomond for many years, see “O’Brien dynasty,” Wikipedia.

[25] See also “’Scandinavian’ in the autosomal DNA ethnicity reports! Should we be excited?,” and “Were Cormac Cas and Eógan Mór really brothers? Testing traditional Irish stories with Y DNA,” both at the Brythonica website maintained by a blogger who is identified only as a writer and historian.

[26] “Cennétig mac Lorcáin,” Wikipedia.

[27] “Mathgamain mac Cennétig,” Wikipedia.

[28] See n. 18 and 26, supra. The chart was created by a Wikimedia Commons user whose username was Claíomh Solais. See also Jack Kirrane’s “Phylogeny Alignment Chart” created for the L-226 Project at FTDNA, the Irish Type III project. This chart includes the Ó Loingsigh/Lynch family and notes that a family with the surname Lindsey has the DNA profile of the Dalcassian Ó Loingsigh/Lynch family. It shows the placement of this family in a flowchart charting the shared ancestry and blood connections of the Dalcassians.

[29] “Killone Abbey Graveyard, Ennis: Transcriptions arranged by Surname,” donated by the Clare Roots Society.

[30] See Samuel Lewis, A Topographical Dictionary of Ireland (London: S. Lewis, 1837), p. 151;“Killone Augustinian Abbey (Nunnery),” at the Monastic Ireland website of the Discovery Programme; “Killone Augustinian Abbey,” at the Heritage Ireland website; “Killone Abbey” at Wikipedia.

[31] See “Newhall House,” at Clarecastle Ballyea Heritage of Clare Community Heritage website; “Newhall, a Comane Family Seat,” a webpage maintained by Newhall’s present owners; and “Newhall House and Estate,” Wikipedia.

[32] “Learned Families of Thomond,” County Clare Library website.

[33] Edward MacLysaght, Irish Families, Their Names, Arms, and Origins (New York: Crown, 1972).

2 thoughts on “Dennis Linchy/Linchey/Lindsey (abt. 1700 – August 1762): The Irish Connection”