James Settles His Family in Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, 1840

The 1840 federal census confirms this information: it enumerates the family of James Birdwell (the spelling here is Burdwell) in Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana.[1] The census shows James with a household consisting of two males 5-9, one male 10-14, and one male 40-49, as well as one female under 5, one female 5-9, two females 15-19, and one female 30-39. Also in the household are fifteen enslaved persons, one male under 10, two males 10-24, one male 24-36, two males 36-55, three females under 10, two females 10-24, two females 24-36, one female 36-55, and one female 55-100.

I’m not quite sure what to make of the listing of these enslaved people in James Birdwell’s household in 1840, since as we’ll see in a moment, James’ succession records after he died in December 1849 show only one enslaved person, a boy named Benton/Ben, whom he bought in January 1848.

The male children enumerated in James’ household in 1840 were John B. (born 1 July 1828), Dewitt Clinton (born about 1831), and Thomas (born 18 June 1832). The female children were Elvira (born about 1822), Hannah (born 25 April 1825), Camilla (born about 1834), and Frances C. (born about 1837). After 1840, Aletha Leonard Birdwell would have daughters Sophronia (born September 1841) and Mary Ann (born about 1845). Elvira was, it appears to me, a young widow living with her parents in 1840, since her husband James Madison Grammer had evidently died not long after the couple married in Marshall County, Alabama, on 17 January 1838.

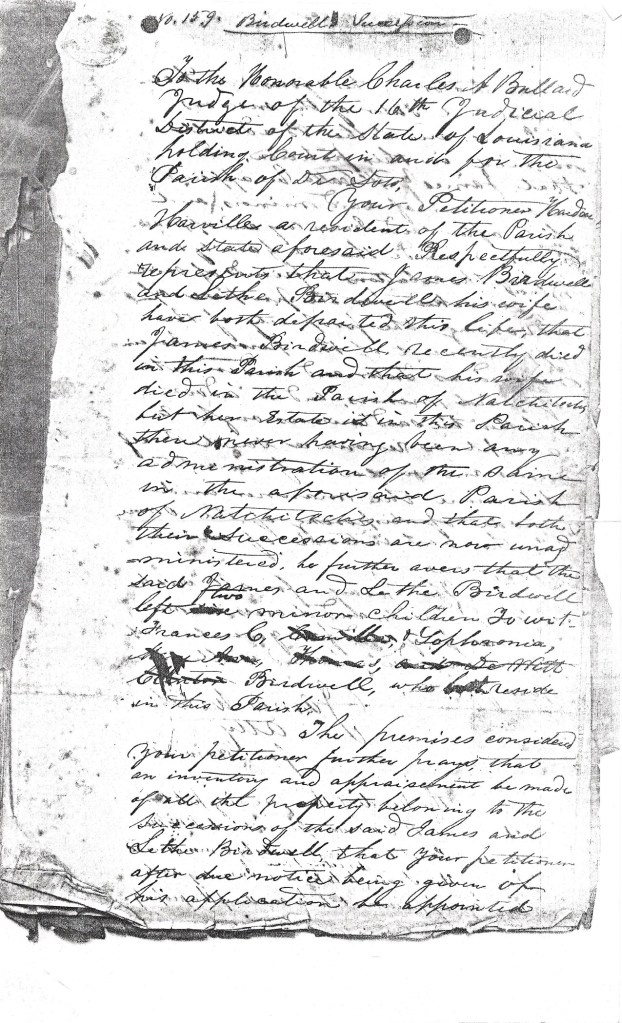

Thomas Dunlap Leonard notes that both James and wife Aletha died a few years after their move to Louisiana, having three married daughters and four younger sons who were not yet grown. I have found records of only three sons of James and Aletha Birdwell. The couple’s oldest daughter Elvira had married on 17 January 1838 in Marshall County, Alabama, before the family left Alabama.[2] Elvira married James Madison Grammer, son of John Grammer and Elizabeth Abernathy. The succession file of James Birdwell in DeSoto Parish shows James’ son-in-law Hardin Harville, who married Hannah Birdwell in Natchitoches Parish on 25 November 1845, petitioning for administration of the succession on 2 April 1850 and stating that James had recently died in DeSoto Parish and his wife Aletha had predeceased him in Natchitoches Parish.[3]

The Lure of Louisiana’s Red River Valley

As the map of Louisiana published in 1856 by J. H. Colton & Co. in New York shows, before Red River Parish was formed from the northern portion of Natchitoches Parish in 1870, most of DeSoto Parish was bordered on its east side in 1840 by Natchitoches Parish, with the Red River forming the boundary between the two parishes.[4] The section of Natchitoches Parish in which James Birdwell settled his family in 1840 was, by all indicators, in the part of Natchitoches Parish that is now Red River Parish. Red River Parish now forms almost the entire eastern boundary of DeSoto Parish (see the map at the head of the posting). A number of families intermarried with James’ family including the Harvilles and Turners owned land on the Red River in both Natchitoches (later Red River) and DeSoto Parishes.

A previous posting about Mark Jefferson Lindsey, whose son Alexander married Mary Ann Green, a daughter of James Birdwell’s daughter Camilla, explains in detail what was motivating settlers who were pouring into the Red River valley area of northwest Louisiana at the time this Birdwell family came there. The linked posting cites historian James David Miller, who notes that as early as the 1830s, cotton planters in the older states of the Southeast were eyeing the fertile Red River valley as the land they had been farming was depleted by exploitative agricultural practices.[5] As the linked posting also indicates, in their book Plain Folk, Planters, and the Complexities of Southern Society, historians Ricky and Annette Pierce Sherrod look at a network of families who moved from the old Southeast to northwest Louisiana in the first half of the 1800s, settling in the Red River valley parishes — especially Natchitoches and its daughter parish Red River. Their study shows that the Red River valley appealed in particular to planters and those aspiring to be planters who hoped to make money growing cotton, since the valley was one of the most prolific cotton-producing regions in the U.S. in the antebellum period.[6] Cotton was fetching a higher price in the Louisiana market than in eastern markets after the economic downturn of the late 1830s, and the Red River region of Louisiana was particularly appealing because it allowed for easy marketing of cotton downriver to New Orleans, with visits to the city by planters for both business and recreation, and for face-to-face meetings with cotton factors.[7]

The promising economic prospects of the Red River valley of Louisiana in this period provided hope to new settlers that if they had arrived in Louisiana as farmers, they might in a few years’ time rise to the status of planters, or if they were already of the planter class, they could further expand their holdings by growing cotton when cotton growing was so lucrative. These promising prospects lured, in particular, farmers from the Tennessee River valley area of north Alabama whose hopes to become rich had been dashed by the economic downturn of the late 1830s – farmers like James Birdwell and members of the Brown and Sherrod families, who are studied in the Sherrods’ book and who also came to the Red River valley in this period from Madison County, Alabama.

James’ Move Across the Red River to DeSoto Parish, 1845-8

Though James Birdwell initially lived in Natchitoches Parish when he settled his family in Louisiana, when he died in December 1849, he was living across the river in DeSoto Parish, as the previous posting shows us, citing the 1850 federal mortality schedule of DeSoto Parish.[8] I think it’s likely that James moved from Natchitoches to DeSoto Parish following his wife Aletha’s death in the former parish, and that Aletha died around the time of the birth of their last child, Mary Ann Birdwell, in 1845. Though the 1870 and 1880 federal censuses show Mary Ann born about 1848, the first census on which she was enumerated, the 1860 census – she was in the Natchitoches Parish household of her sister Sophronia and Sophronia’s husband Lewis Livingston Turner – has her born in 1845, and that date appears to me to be correct.[9] I think it’s possible that Aletha died giving birth to Mary Ann, though I have no information to prove (or disprove) that deduction.

James Birdwell was still in Natchitoches Parish on 25 November 1845, since the contract for the marriage of his daughter Hannah to Hardin Harville on that date states that the couple married at the home of the bride’s father James Birdwell in Natchitoches Parish.[10] But by 25 January 1848, James had moved to DeSoto Parish. On that date in DeSoto Parish, Josiah Miles sold James Birdwell an enslaved boy named Ben, aged about ten, for $400.[11] The conveyance record, which was witnessed by James’ son-in-law Hardin Harville and his son John Birdwell, states that both Miles and Birdwell lived in DeSoto Parish. Hardin Harville affirmed the conveyance on 4 April 1848.

Mexican War Service

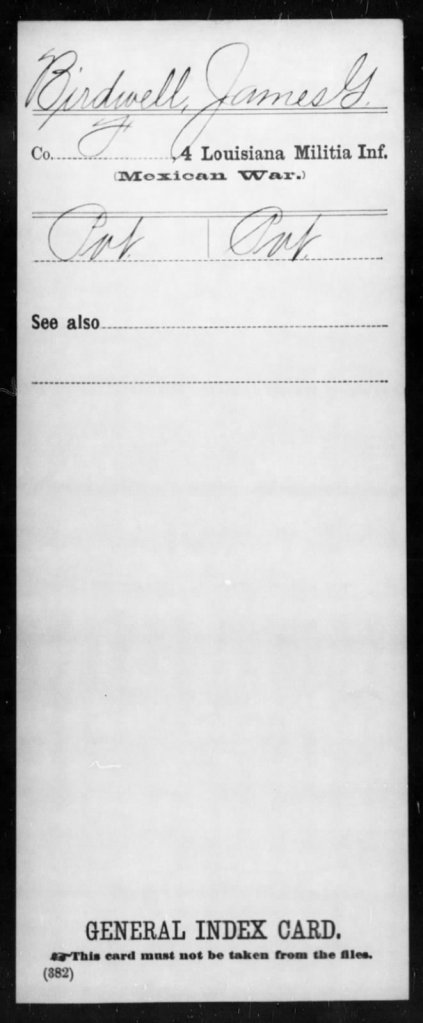

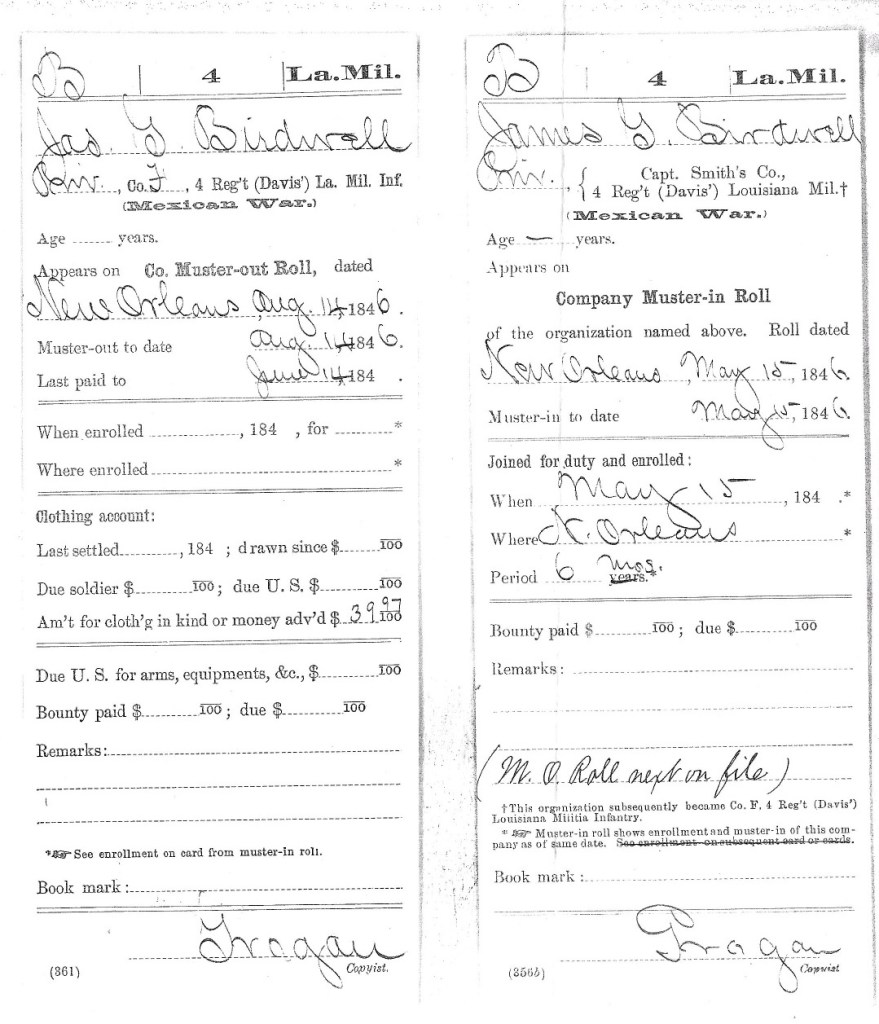

As a previous posting states, on 15 May 1846 in New Orleans, James G. Birdwell enlisted in Co. F of the 4th Louisiana Militia Infantry for six months’ service in the Mexican War.[12] I know of no other James Birdwell living in Louisiana at this point than the son of Moses Birdwell, who arrived in Natchitoches Parish in 1840, so I’ve concluded that this James G. is James Birdwell of Natchitoches Parish.

The two cards in James G. Birdwell’s service file show that after he enlisted in New Orleans on 15 May 1846 for six months’ service, he was mustered out in New Orleans on 14 August 1846 and was paid on 14 June – the year is not specified – $39.97. He was in Colonel Horatio Davis’ regiment of General Persifor Frazer Smith’s company of Louisiana Infantry Volunteers. On the day of James G. Birdwell’s enlistment, the New Orleans paper The Bee reported (p. 1, col. 3) that 2,392 men had been mustered in for service in New Orleans the preceding day. On 16 May, The Bee stated that New Orleans had supplied 3,000 men for the war effort, and that this did not include men who had arrived or might yet arrive to enlist from other parts of Louisiana.

Though James Birdwell enlisted in the 4th Louisiana Militia Infantry in New Orleans, that military unit had strong ties to the area of Louisiana in which he lived. The 4th Infantry was part of Zachary Taylor’s “Army of Observation” at Fort Jesup as tensions between the U.S. and Mexico heated up in the 1840s.[13] Fort Jesup is little more than ten miles west from where James Birdwell settled in Natchitoches Parish. Zachary Taylor was stationed there as the fort commander in the 1820s. In 1844, as the situation with Mexico heated up, the 4th Infantry was ordered to the western border of Louisiana to defend that part of Louisiana from Mexican incursion. In the summer of 1845, Taylor was back at Fort Jesup after having been stationed elsewhere and then began moving troops into Texas, apparently with the intent of attacking Mexico when the time seemed ripe. After Colonel Truman Cross was murdered by Mexican banditti on 10 April 1846, Taylor, who had been amassing troops in Texas, invaded Mexico, with the 4th Infantry taking part in this invasion.

In joining the 4th Louisiana Militia Infantry on 15 May 1846 a little more than a month after Truman Cross’ murder, James Birdwell was enlisting in a military unit that had strong historic ties to the area of Louisiana in which he lived. I suspect that by the time James enlisted in the 4th Louisiana in May 1846, his wife Aletha had died, and that while he did military service, he left the operation of his farm to his oldest son John, who was just turning eighteen, and to his son-in-law Hardin Harville.

James Dies in DeSoto Parish, December 1849 – Succession Records

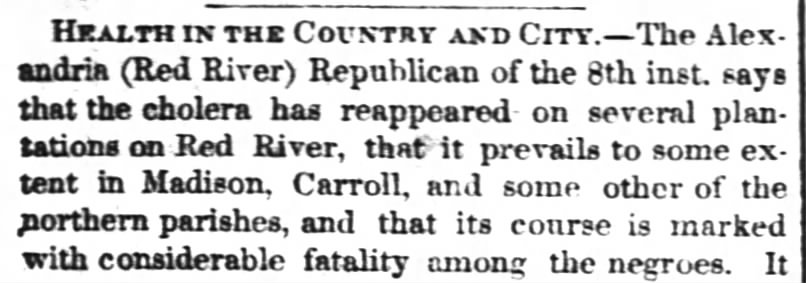

As we’ve seen, by the time he purchased Benton/Ben in January 1848, James Birdwell was living in DeSoto Parish. In December 1849, he died in DeSoto Parish. As the previous posting notes, his listing on the DeSoto Parish mortality schedule in 1850 states that he was a planter aged 54, born in Georgia, and that he died of cholera.[14] Listed beside James on this mortality schedule is a girl Mary, whose race is denoted as Black, who died aged one month in January (1849?) of unknown causes. Mary’s mother would, I think, have been an enslaved person belonging to James Birdwell.

On 15 December 1849, the New Orleans Times-Picayune reported that the Alexandria Republican had stated on the 8th that cholera had appeared on several plantations along the Red River.[15] Cholera tended to travel along riverways and had broken out in New Orleans by November 1849, and was then brought to St. Louis when the steamboat The Constitution arrived in that city from New Orleans on 15 November, with thirty-five people aboard the steamboat sick with cholera and seventeen having died from it en route to St. Louis.[16] New Orleans had been relatively free of cholera outbreaks up to 1848, when the disease returned, evidently brought aboard ships from Europe and the British Isles, and the city then experienced devastating waves of cholera for a number of years, with many deaths. After showing up in New Orleans and New York in December 1848, the disease had spread to Nashville by January 1849, with illness increasing there through the summer and perhaps causing the death of former president James K. Polk.

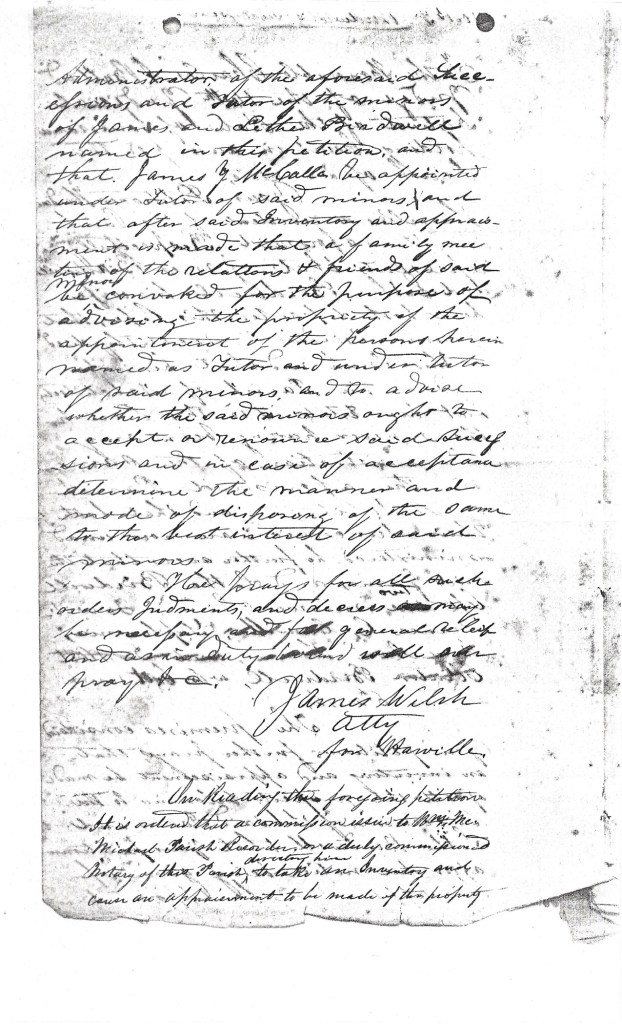

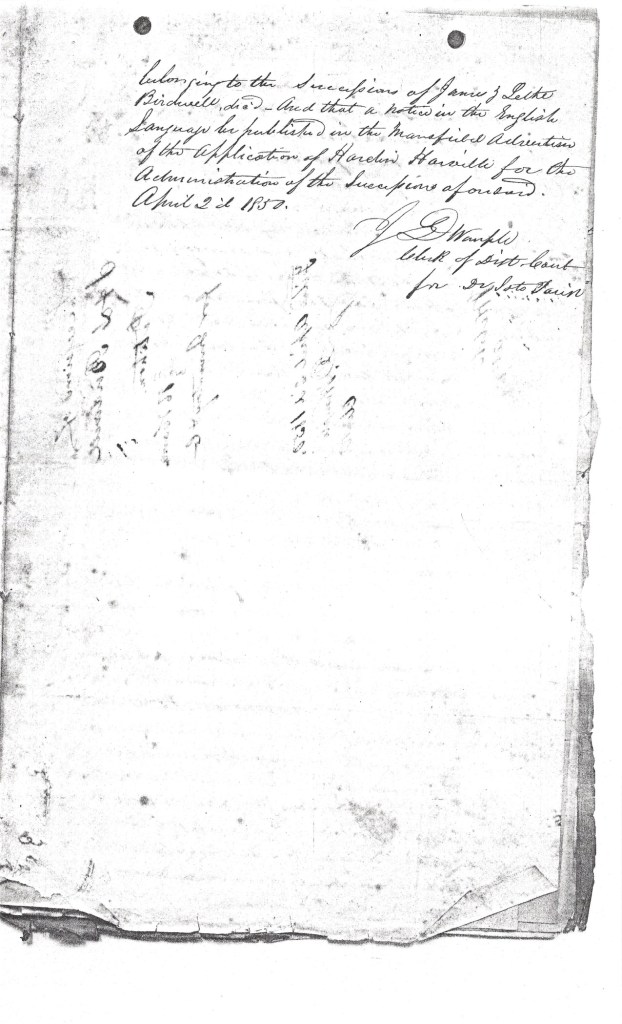

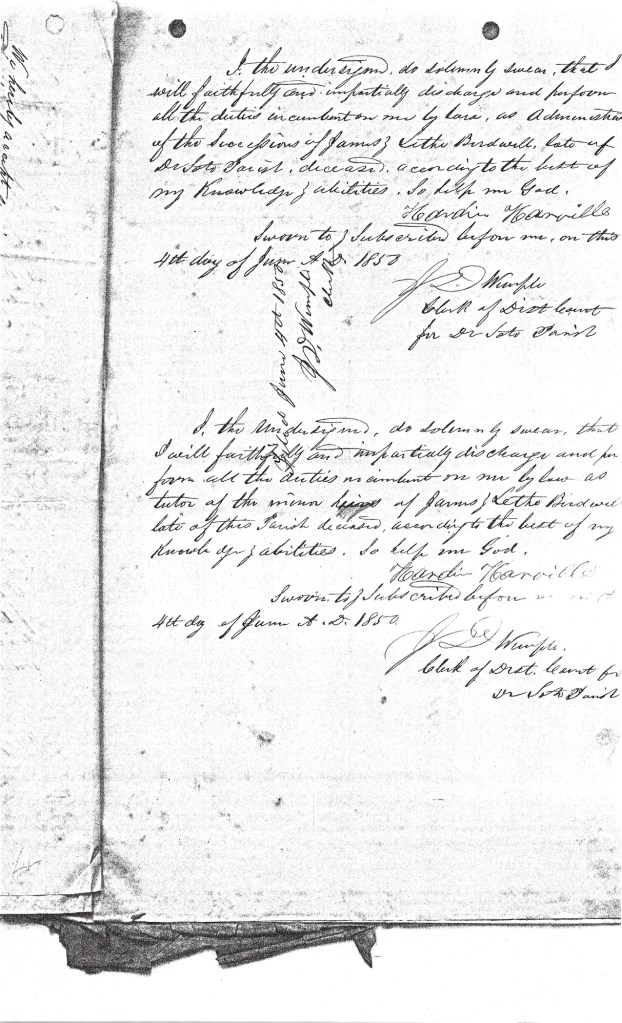

As noted above, on 2 April 1850, Hardin Harville petitioned in DeSoto Parish for administration of the succession of his father-in-law James Birdwell, with James Welsh acting as attorney for Harville.[17] The petition states that James Birdwell had recently died in DeSoto Parish and had been predeceased by his wife Lethe, who died in Natchitoches Parish. The petition also states that James and Lethe left six minor children, Frances C., Camilla, Sophronia, Mary Ann, Thomas, and DeWitt Clinton Birdwell. The names of all children except Frances C. and Sophronia are crossed out, and the word “two” written over “six.” This petition notes that the two minors (Frances and Sophronia) were living in DeSoto Parish. The petition also requests that James Y. McCalla be appointed tutor of the minors. As it received the petition for administration, the court ordered that the succession be published in the Mansfield Advertiser. Mansfield is the parish seat of DeSoto Parish.

James Welsh was an attorney living in DeSoto Parish, and when the first parish court convened in June 1843, he was judge of the court.[18] The 1850 federal census, which gives his surname as Welch, shows him in the western district of DeSoto Parish, and states that he was a lawyer, aged 43, and born in Louisiana.[19]

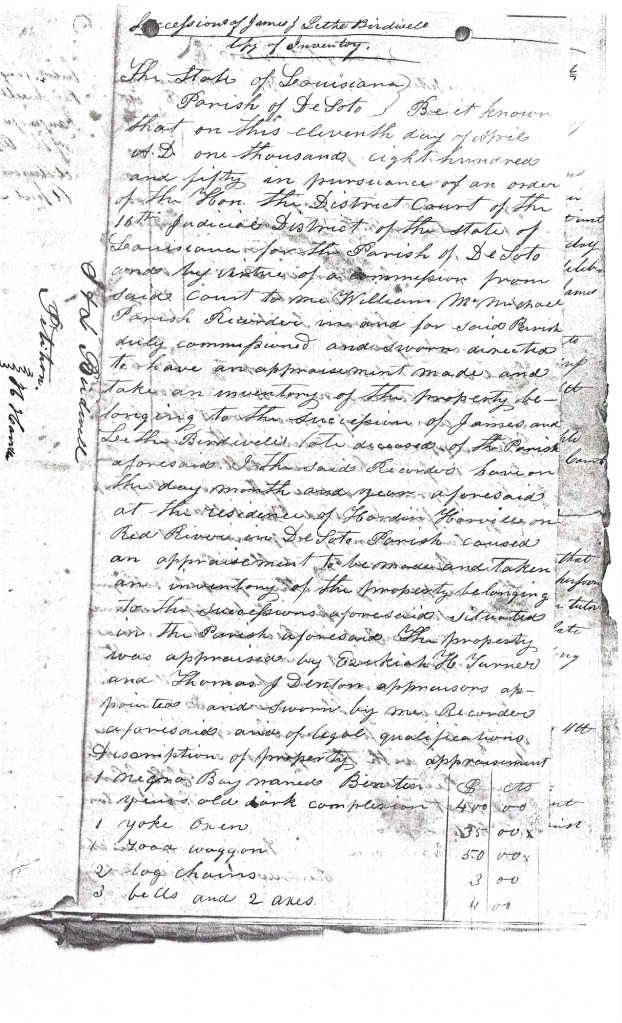

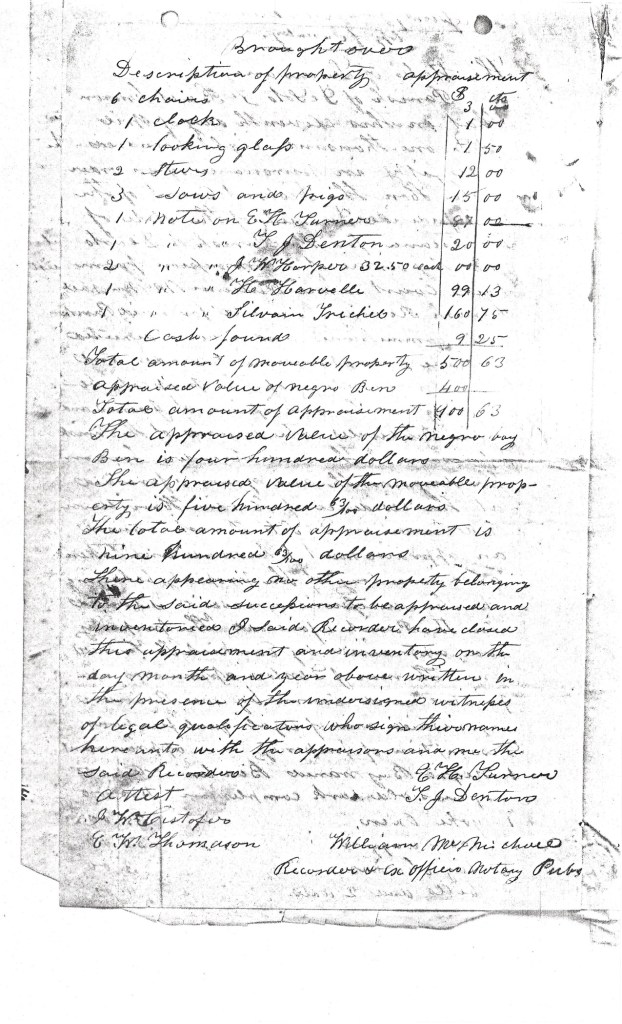

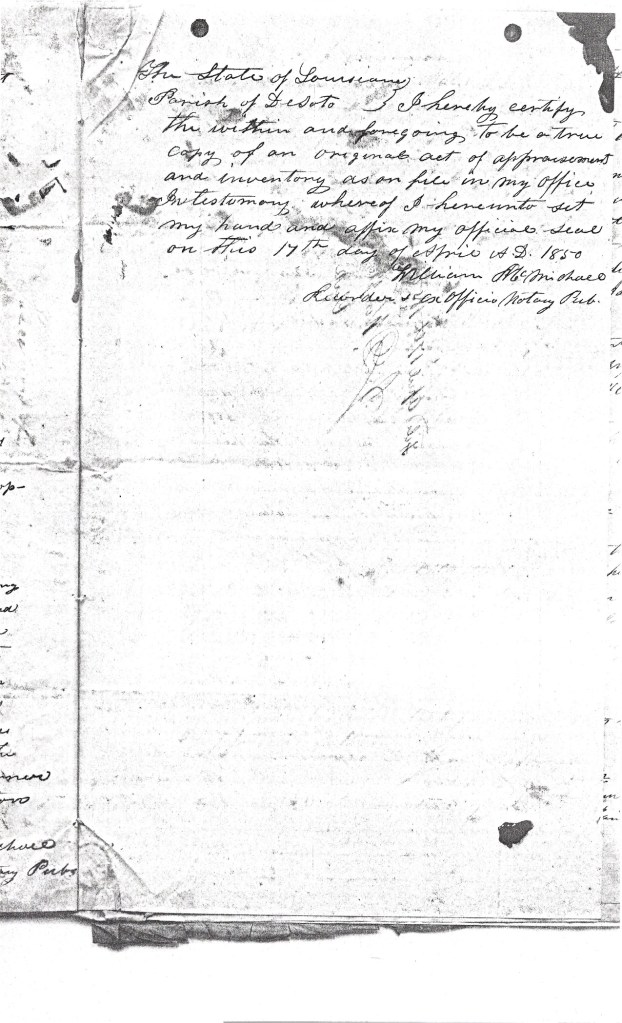

The succession was appraised and inventoried on 11 April 1850 by Ezekiah H. Turner and Thomas J. Denton. The succession included the enslaved boy Ben whom James Birdwell had bought from Josiah Miles in January 1848, and whose name is given here as Benton. Benton was valued at $400; various items of farm equipment and household furniture are also enumerated, along with promissory notes that James Birdwell held on Turner and Denton, J.W. Harper, Hardin Harville, and Silvain Trechel. The succession’s movable property was appraised at $900.63. The appraisal and inventory were recorded on 17 April 1850.

Ezekiah H. Turner appears in other records as Elias Hampton Turner. Two of his children, Lewis Livingston Turner and Virginia Turner, married children of James Birdwell – Sophronia and Thomas Birdwell. He was in Natchitoches Parish by 1840, having come there from Mississippi, and then settled on the Red River in DeSoto Parish, where he died in January 1862, with his children and heirs selling his 640-acre plantation on the Red River on 23 March 1870.[20] A biography of Ezekiah’s son Robert Hampton Turner in Memorial and Biographical History of McLennan, Falls, Bell, and Coryell Counties, Texas describes Ezekiah as “a wealthy planter… [who] had a fine estate on Red River.”[21]

I wonder if the J.W. Harper for whom James Birdwell held a note may have been James Washington Harper of Shelby County, Alabama. James died in that county on 9 August 1840. His widow Rebecca (née Morgan) moved from Alabama to Claiborne Parish, Louisiana, with their children in 1849 and subsequently received a grant for land in Natchitoches Parish for James W. Harper’s War of 1812 service in Georgia. Because promissory notes functioned as a kind of currency, they could pass from hand to hand even after the death of the person who originally signed the note.

On 4 June 1850, the court ordered George R. Draughon, Charles Holden, Rezin E. Mabry, John J. Clow, and John Wemple to convene a family meeting on the 8th. These men made oath on the 4th. The same day, James Y. McCalla gave oath to be tutor of James Birdwell’s minors, and Hardin Harville gave oath to administer the succession. On 4 June, Harville and John A. Quarles gave bond in the amount of $1,352 for the administration.

The record of the family meeting notes that it was agreed at the meeting to make James Y. McCalla under-tutor of the minors, and Hardin Harville their tutor. It was also agreed that the movable property, including the enslaved boy Ben, was to be sold. On 5 June 1850, Hardin Harville prayed for homologation, with the order for homologation given on 2 December 1850.

The act of sale is dated 14 January 1851, with the farm and household items going to M.H. Stattings for a sum of $101.80, and the enslaved boy Ben going to Samuel Clark for $560. The sale was filed by Hardin Harville on 18 February 1852.

I don’t know of a family connection between James Y. McCalla, who was appointed under-tutor of James Birdwell’s minor children, and James Birdwell. The 1850 federal census shows him living in the western district of DeSoto Parish, where Hardin Harville and wife Hannah Birdwell also lived in 1850, and listed as a blacksmith aged 43, born in South Carolina.[22] James Y. McCalla is buried in State Line cemetery at Texarkana, Miller County, Arkansas, with a tombstone stating that he was born 5 April 1807 in Chester County, South Carolina, and died 23 February 1888.[23] James McCalla’s wife is said to have been Elizabeth Lynch.

Notes on Children of James Birdwell and Aletha Leonard

As I noted above, James Birdwell’s succession documents name six children, the six youngest of his children, of whom two were minors when James died: Dewitt Clinton, Thomas, Camilla, Frances C., Sophronia, and Mary Ann. Since Mary Ann appears to have been James and Aletha Leonard Birdwell’s last child, it’s not clear to me why Frances and Sophronia are listed as the two minors, but not Mary Ann. As I’ve noted previously, we know from the marriage contract of James’ daughter Hannah when she married Hardin Harville in Natchitoches Parish on 25 November 1845 that Hannah was another daughter of James and Aletha.

As a previous posting has noted, a lawsuit filed on 3 December 1850 by Samuel Kerr Green, who married Elvira Birdwell on 13 June 1844 after the death of her husband James Madison Grammer, states that on 20 January 1848 Samuel had come into possession of a note made by A.H.F. Duke to Samuel’s father-in-law on 3 November 1847. Henry Andrew Duke died in Natchitoches Parish in 1848 not long after he moved there from Perry County, Alabama, and his succession was being administered by M.F. Carter. Samuel K. Green was suing Carter as administrator of Duke in Natchitoches Parish to recover the debt.[24] Duke’s note to James Birdwell was co-signed by Henry Paulin Welch/Welsh, whose wife Julia Ann Yocum Welch/Welsh testified in the lawsuit filed by Samuel’s son Ezekiel Samuel Green in Pointe Coupee Parish when Samuel refused to give Ezekiel property left to him by his mother Eliza Jane Smith. Henry Paulin Welch/Welsh and wife Julia are discussed in a previous posting.

The Natchitoches Parish lawsuit Samuel K. Green vs. M.F. Carter proves that Elvira Birdwell, who, as we’ve seen, married James M. Grammer in January 1838 before James and Aletha Leonard Birdwell left there to move to Louisiana, was another child of James and Aletha. The lawsuit shows Samuel K. Green, as James’ son-in-law, holding a promissory note that had come to him from his father-in-law following Samuel’s married to James’ daughter Elvira.

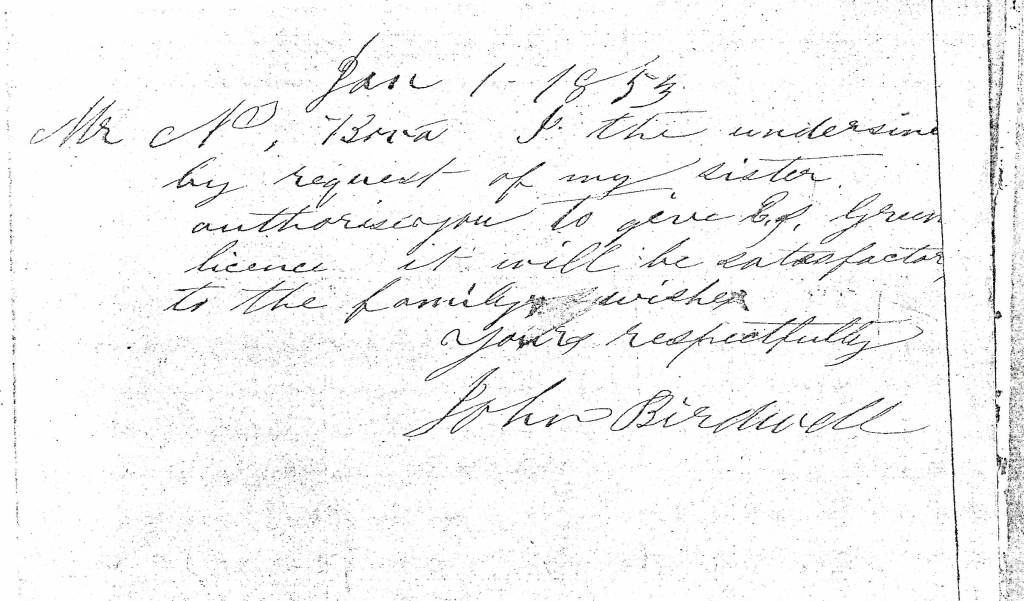

Another of James Birdwell and Aletha Leonard’s children, John B. Birdwell, can be proven by the permission note that John wrote on 1 January 1853 to give his permission as the male head of this Birdwell family when his sister Camilla married Ezekiel Samuel Green in Pointe Coupee Parish on 2 January 1853. That permission note is discussed in a previous posting. The note states that Camilla was John’s sister, and, as we’ve seen above, Hardin Harville’s petition to administer the succession of James Birdwell states that Camilla was James’ daughter.

I have no information about where James Birdwell and his wife Aletha are buried. It has been suggested that James may be buried at Robeline in Natchitoches Parish, where members of a Birdwell family that is not related to the family of James Birdwell have been buried for a number of generations. This family descends from an Ezekiel Bardwell (1791-1870) whose surname shifted to Birdwell after this family moved to Louisiana.

In my next posting, I’ll provide more information about the children of James Birdwell and Aletha Leonard.

[1] 1840 federal census, Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, p. 173.

[2] Marshall County, Alabama, Marriage Bk. 1838-1848, p. 32. The loose-papers marriage file in Marshall County shows James M. Grammer giving bond with Bazel R. Starnes on the 17th, and James and Elvira receiving license on the same day. George Lay, j.p., returned the marriage to court on the 18th. See also Pauline Jones Gandrud, Alabama Records, vol. 65: Marshall County, p. 63.

[3] DeSoto Parish, Louisiana, succession file no. 159; and DeSoto Parish, Louisiana, Succession Bk. D, pp. 643-650.

[4] See 1856 map of Louisiana, published by J. H. Colton & Co. of New York, available digitally at Wikimedia Commons. See also this previous posting.

[5] James David Miller, South by Southwest: Planter Emigration and Identity in the South and Southwest (Charlottesville: Univ. of Virginia, 2002), p. 103.

[6] Ricky L. Sherrod and Annette Pierce Sherrod, Plain Folk, Planters, and the Complexities of Southern Society: A Case Study of the Browns, Sherrods, Mannings, Sprowls, and Williamses of Nineteenth-Century Northwest Louisiana (Nacogdoches: Stephen F. Austin University Press, 2014), p. 85.

[7] Ibid., p. 57.

[8] 1850 federal mortality schedule, DeSoto Parish, Louisiana, p. 168, l. 11.

[9] 1860 federal census, Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, p. 153 (dwelling/family 1311; 1 October).

[10] Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, Conveyance Bk. 37, p. 114, no. 1998.

[11] DeSoto Parish, Louisiana, Conveyance Bk. A, p. 496.

[12] NARA, Indexes to the Carded Records of Soldiers Who Served in Volunteer Organizations During the Mexican War, compiled 1899 – 1927, documenting the period 1846-1848, RG 94, available digitally at Fold3.

[13] Patricia Heintzelman, “Fort Jesup,” National Register of Historic Places Inventory, online at National Park Services website; John G. Belisle, History of Sabine Parish, Louisiana (Many, Louisiana: Sabine Banner Press, 1913); “Army of Occupation (Mexico),” Wikipedia; and Chris Kolakowski, “’The Warriors’ Regiment: 4th US Infantry,” at American Battlefield Trust website.

[14] See supra, n. 8.

[15] “Health in the Country and City,” Times-Picayune [New Orleans] (15 December 1849), p. 2, col. 1.

[16] “The Cholera,” Times-Picayune [New Orleans] (17 November 1849), p. 2, col. 4.

[17] DeSoto Parish, Louisiana, succession file no. 159; and DeSoto Parish, Louisiana, Succession Bk. D, pp. 643-650.

[18] Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Northwest Louisiana, Comprising a Large Fund of Biography of Actual Residents, and an Interesting Historical Sketch of Thirteen Counties (Nashville and Chicago: Southern, 1890), p. 239.

[19] 1850 federal census, DeSoto Parish, Louisiana, western district, p. 167B (dwelling 82/family 79; 20 August).

[20] DeSoto Parish, Louisiana, Conveyance Bk. N, pp. 215, 221.

[21] Memorial and Biographical History of McLennan, Falls, Bell, and Coryell Counties, Texas (Chicago: Lewis, 1893), pp. 570-571.

[22] 1850 federal census, DeSoto Parish, Louisiana, western district, p. 166B (dwelling 62/family 58; 20 August).

[23] See Find a Grave memorial page of James Y. McCalla, State Line cemetery, Texarkana, Miller County, Arkansas, created by Becky Akin, with a tombstone photo by KindredWhispers.

[24] Samuel K. Green vs. M.F. Carter, administrator of A.H.F. Duke, Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, District Court case file no. 4326, bundle 190.

5 thoughts on “James G. Birdwell (1795-1849): Louisiana Years”