Here’s an experience I’ve had, oh, once or twice (including in my several decades of doing family history): I’m motoring along, absolutely certain I know where I’m headed, and all of a sudden, a signpost appears by the roadside telling me I’ve been on the wrong road all the time. When I was certain I knew where I was going — certain that I knew what I knew. . . .

Perhaps something similar has happened to you? If so, this may be a story for you. It’s a story that contains everything but the kitchen sink — a murder, a father trying to bastardize a son, an out-of-wedlock birth, the sordid history of slavery in the U.S. and how that institution ate away at the souls of slaveholders even as it treated human beings as chattel property to be bought, sold, and used at will. It’s a story of a father and son who, between them, married three sisters. And it’s a story of wheeling and dealing — lots of wheeling and lots of dealing.

It’s a small piece of a much larger and complex story that I plan to tell fully in a subsequent series of postings under this title. For now, I want to tell you about that surprising volte-face I’ve just experienced, when an unexpected new tidbit of information about one of my ancestors suddenly deconstructed key “facts” I thought I knew about him and his first wife. That ancestor is Ezekiel Samuel Green (1824 – 1900/1910) and his first wife is Camilla Birdwell (1834 – aft. 4 December 1865).

What I thought I knew: Camilla died in childbirth 11 October 1862 in Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, giving birth to her and Ezekiel’s daughter Mary Ann Green (1862-1942), my great-grandmother. A cousin whose grandmother Camilla Green Lindsey was a daughter of Mary Ann Green and her husband Alexander Cobb Lindsey (1858-1947) told me she thought she had heard her grandmother state this.

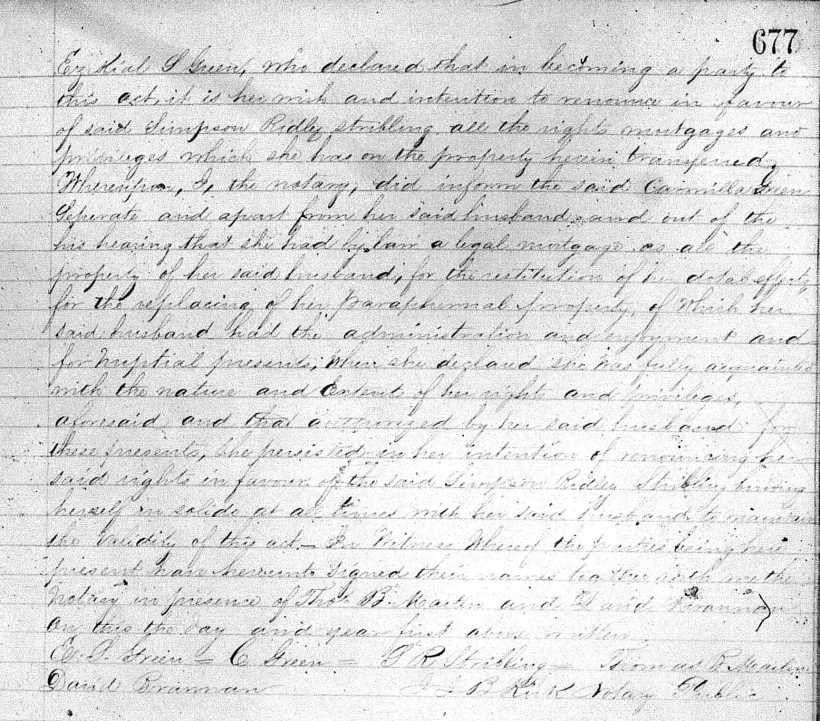

When I learned this piece of information, it seemed to fit: the last record I had been able to find of Camilla, before she gave birth to daughter Mary Ann on 11 October 1862, was a conveyance record dated 30 January 1862 in Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana, when she and her husband Ezekiel sold 199.48 acres in that parish to Simpson Ridley Stribling, the record stating that all parties lived in the parish, and Camilla renouncing her dower rights on that same date (Avoyelles Conveyances Bk. FF, pp. 676-7).

On 11 December 1867, Ezekiel married Camilla’s sister Hannah, who was the widow of Hardin Harville, in Natchitoches Parish with (inter alia) Edwin Thomas Friend (1813-1897) witnessing the marriage (Natchitoches Psh. Marriage Bk. 5, p. 76). Edwin’s son George Adolphus Friend (1839-1913) married Camilla and Hannah’s sister Mary Ann Birdwell (abt. 1845 – abt. 1885). George’s sister Sarah Matilda Friend (1850-1927) married Joseph Clark Harville (1851-1919), a son of Hannah Birdwell by her first husband Hardin Harville.

The January 1862 conveyance record in Avoyelles Parish, followed, of course, by the birth of her daughter Mary Ann in October 1862, and the December 1867 marriage record in Natchitoches Parish told me that Camilla Birdwell Green died between the October 1862 date and the December 1867 one — in Avoyelles Parish, I had surmised, though the death certificate of my great-grandmother Mary Ann Green Lindsey, for which my great-grandfather Alec C. Lindsey supplied the information, states that Mary Ann was born 11 October 1862 in Pointe Coupee Parish (Louisiana State File 1620, Red River Parish).

This is what I thought I knew, then — until two days ago. Between that January 1862 sale of land in Avoyelles Parish and the December 1867 marriage in Natchitoches Parish, Ezekiel also disappears from Avoyelles records and I find no trace of him in Natchitoches. I had conveniently bracketed these lost years (lost to my tracking, that is) as, “Oh, undoubtedly off doing military service in the Civil War” — though I had not found a Civil War service record for Ezekiel.

Then this happened: I was searching tax lists in Texas, using the handy search engine for that task provided at the FamilySearch website, and I thought I’d see if anything turned up when I entered “E.S. Green” or “Ezekiel S. Green” into that search engine. I knew that Ezekiel had inherited 640 acres in Llano County, Texas, from his father Samuel Kerr Green (1790-1860), and that he had sold that piece of land on 16 February 1891, with the deed noting that Ezekiel was living in St. Landry Parish, Louisiana, when he sold the tract of land (Llano DB T, pp. 53-4).

I also knew that of Ezekiel’s six children by his third wife Mary Ann Wester (1857-1909), whom Ezekiel married in Red River Parish, Louisiana, on 13 January 1876, four had gone to Texas. I have never found a definite date of death for Ezekiel, and as I comb records in Louisiana for that information, I always keep in mind that he might well have spent the final years of his life in Texas, given his many family ties to that state.

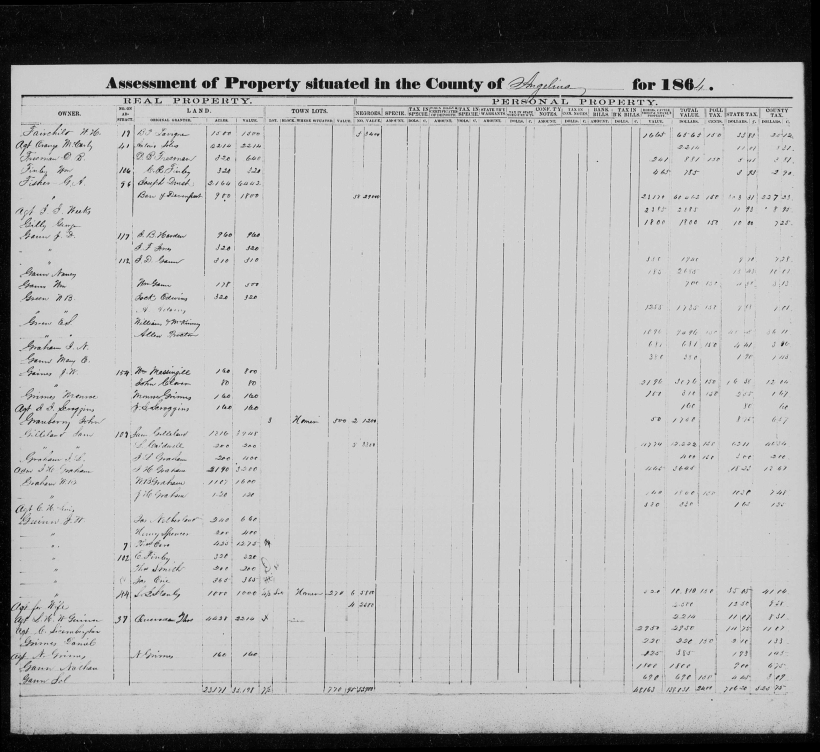

When I did my search for E.S. or Ezekiel S. Green in Texas county tax lists, an interesting record popped up: I found that an E.S. Green was on the Angelina County, Texas, tax lists in 1864 and 1865, taxed for 480 acres. Could that possibly be my E.S. Green, I wondered?

To answer that question, I needed to search the deed records of Angelina County to see if I could find a record of this land, when and by whom it was bought, when and by whom it was sold. When I did that, here’s what I discovered. . . .

But first you need to know the backstory to this story — you need to know at least the broad outlines of this backstory — to appreciate what I’m about to report to you. Here are the bare bones of this backstory:

Ezekiel married Camilla Birdwell, daughter of James Birdwell and Aletha Leonard, in Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, on 2 January 1853. The marriage file containing the bond that Ezekiel gave on the day of his marriage with Reason Cripps contains an interesting document, a note dated 1 January from Camilla’s brother John B. Birdwell (1828-1918) giving the family’s permission for her to marry. Camilla was 19 at the time. Her father James had died in December 1849 in De Soto Parish, and her mother Aletha had died about 1845 in Natchitoches Parish. John was the oldest son in the family and now acting as the head of the family.

The reason Ezekiel was in Pointe Coupee Parish in 1853 was that his father Samuel Kerr Green had married a well-to-do widow, Elvira Birdwell (abt. 1822-1855), the widow of James Madison Grammer (1812-1844) in Natchitoches Parish on 13 June 1844, and had settled with Elvira in Pointe Coupee Parish, where her deceased husband had left her a nice tract of land. Elvira was Camilla’s sister. Between them, the father Samuel and his son Ezekiel married three Birdwell sisters, daughters of James and Aletha Leonard Birdwell.

At some point around 1823, while he was working as an overseer on sugarcane plantations in Plaquemines Parish south of New Orleans, Samuel had entered a marital arrangement with a previous spouse, a woman named Eliza Jane Smith, whom he would later claim he had not ever married. I’ll tell you in a moment how I know this fact. Samuel and Eliza had separated around 1829, after the birth of their son Ezekiel Samuel Green about 1824, and in 1830-1, Eliza then remarried to Capt. Samuel Ives, a Connecticut-born fellow who had, among other property, a sawmill business in Iberville Parish at Bayou Sorel — pay attention to that mention of a sawmill; this theme will recur in the story I’m telling you about Ezekiel S. Green. Eliza lived with Samuel Ives in New Orleans, St. Martinville, and Iberville Parish, and then between 1835-7, that marriage ended and Eliza began living on her own, resuming her maiden name, in Iberville Parish. (Samuel Ives also continued in that parish until his business partner Alden Piper murdered him there on 2 June 1850).[1]

Not long before she married Ives, Eliza Jane Smith had acquired — again, using her maiden name — a family of slaves from Samuel Woolfolk of New Orleans on 10 May 1829. The conveyance record noting this sale states that Eliza lived in Plaquemines Parish, and names the slaves she bought: Amy, 29, and her 3 children, Hetty, 7, John, 4, and Batt/Baptiste, 10 (Plaquemines Parish Notarial Bk. 4, #714, p. 276 [Register 17, #4, p. 714]). I’m drawing your attention to these enslaved people and Eliza’s purchase of them because they figure largely in the story of Ezekiel S. Green and his father Samuel K. Green, and what became of their father-son relationship. Woolfolk was a slave trader from a Maryland family who had a business on Chartres Street in New Orleans.[2]

On 23 November 1841, Eliza Jane Smith sold her property at Bayou Sorel in Iberville Parish (except, the conveyance record notes, for a large armoire, her riding horse, a bedstead and bedding, a large copper kettle, and her table silver spoons — and, of course, the slaves she had bought in New Orleans) (Iberville Parish Conveyance Bk. U, p. 332). By this time, her first spouse Samuel K. Green had set himself up on a nice plantation of 640 acres in Natchitoches Parish, which he purchased 1 October 1835 from Dr. John Sibley. The land was 15 miles west of the town of Natchitoches at the old Spanish fort and settlement, Los Adaes (Natchitoches Parish Conveyance Bk. 22, p. 110, #578).[3]

As he bought his plantation in Natchitoches Parish, Samuel contracted with John Hartman, a carpenter, to build him a nice house on the land. Hartman’s widow Mary filed suit against Samuel on 15 August 1838 for not having paid her husband; the court file for the case includes a detailed description of the house Hartman built: it was a two-story house with two rooms eighteen feet square on each floor, a central hall fourteen feet wide, a gallery across its front on both stories, and chimneys at either end of the house (Natchitoches Parish District Court file 1986, Parish Court file 283). This description shows that Samuel was replicating a house, somewhat larger, that his parents John Green and Jane Kerr had built in Bibb County, Alabama, a few years prior to this in the early 1830s, after they moved there from Anderson County, South Carolina, in 1819. I have visited that house and taken photos of it.

As the debt case filed by Mary Hartman suggests, all was not well with Samuel by the late 1830s — not well financially. He was wheeling. He was dealing. And he was short of funds. In his dispute with Mary Hartman, he stated that her husband’s workmanship had been so shoddy, he had to have much of the house pulled down and had to hire another carpenter to redo the work. The wheeling and dealing: this is a pattern I find replicated in his son Ezekiel’s life, so that even though father and son came to legal blows (as I’ll explain later), this appears to be a case of, Like father, like son.

Another Natchitoches Parish case in 1837 shows Samuel suing Elijah Clark for claiming ownership of the 640 acres Samuel had bought from John Sibley in 1835. Samuel filed this suit 21 November 1837, claiming that Clark was cutting timber on his land. The case file has a receipt dated 21 March 1840 confirming Samuel’s plat to the land (Natchitoches District Court file 1635; see also Natchitoches District Court Bk. C, pp. 428-9).

On 10 January 1837, Samuel purchased the 640 acres in Llano County, Texas, I mentioned to you above. He bought the property in New Orleans from Hansford Cophendolpher.[4] A few months after this, Samuel went up to Smithfield, Kentucky, to visit his brother Ezekiel Calhoun Green and to borrow $150 from that Ezekiel, something we know because, when his brother’s estate was settled in 1851 in Livingston County, Kentucky, the administrator, James K. Huey, called in the debt and filed suit against Samuel in Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana. The case file for the lawsuit has Samuel’s promissory note with his signature (Pointe Coupee 9th District Court case file 932).

As I tell you about Samuel’s financial woes (and his wheeling and dealing) after he had set himself up on a plantation in Natchitoches Parish, I’m setting the stage for you to appreciate the importance of what then happened in his life — and how this affected his relationship with his son. Remember that I’ve told you his first partner Eliza Jane Smith, whom he would later claim he had never married, sold out her property in Iberville Parish in November 1841?

The reason she did this is that she was returning to Samuel K. Green in Natchitoches Parish. Eliza Jane died at Samuel’s house about 13 March 1843 (and, again, I’ll tell you later how I know these facts), having made a will on the 1st of March (it was filed on the 18th) leaving her property to Samuel K. Green, and, in the event of his demise, to a Jackson and Minerva Smith of Kentucky. The will specifies that her property included slaves named Amey, John, Hetty, Batt, Maria, Charles, and Lady (Natchitoches Conveyance Bk. 34, p. 130, #3422).

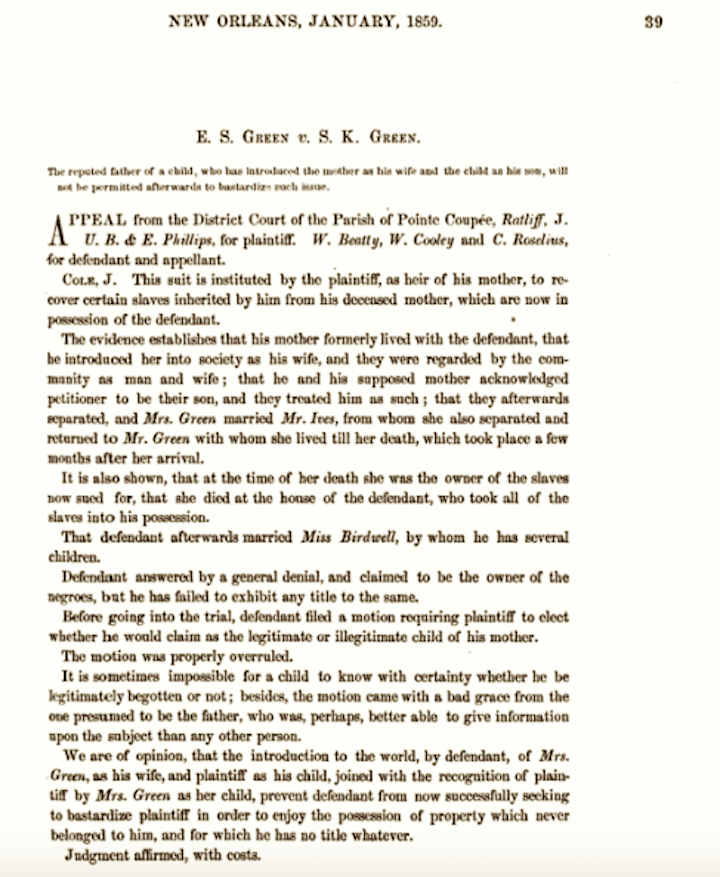

Samuel needed those slaves and their labor. Or, perhaps more accurately, he wanted those slaves. He wanted them enough, in fact, that he chose to deny his and Eliza Jane’s son Ezekiel any share of their ownership: he chose, in fact, to bastardize Ezekiel, to claim that he and Eliza Jane had never married and he was not Ezekiel’s father, to claim sole ownership of those slaves.

The reason Samuel coveted the slaves Eliza Jane left when she died — the reason he wanted sole ownership of them — becomes even more apparent in a number of documents in the years 1844-6. On 3 January 1844, Samuel mortgaged his plantation to St. Francis Church in Natchitoches for $1,500; his October 1835 note to Dr. John Sibley purchasing his land in Natchitoches Parish had fallen into the hands of the church (Natchitoches Parish Mortgage Bk. A, pp. 126-7). On 13 October 1845, St. Francis church filed suit against Samuel for $500 due on the mortgage (Natchitoches Parish District Court file 3734). On 20 November, the parish court found in favor of St. Francis church and ordered that Samuel’s land be seized and sold for debt (Natchitoches Parish Judicial Mortgage Record C, pp. 154-5).

On 7 February 1846, the land was sold to St. Francis church for $1,334 (Natchitoches Psh. Sheriff’s Sales Bk. 5, pp. 26-7; recorded 7 Feb., filed 10 March 1846). On 7 January 1848, Samuel ratified the sale of the 640-acre plantation to Ambrose Lecompte, warden of St. Francis church (Natchitoches Parish Conveyance Bk. 39, p. 417, #4749).

And now back up a minute and remember that I’ve told you the reason Ezekiel S. Green was in Pointe Coupee Parish in 1853 when he married Camilla Birdwell was that his father Samuel Kerr Green had married a well-to-do widow, Elvira Birdwell (abt. 1822-1855), the widow of James Madison Grammer (1812-1844) in Natchitoches Parish on 13 June 1844, and had settled with Elvira in Pointe Coupee Parish, where her deceased husband had left her a nice tract of land.

We get a glimpse of the property Elvira owned following the death of her first husband James M. Grammer from Elvira’s succession record in Pointe Coupee Parish (Pointe Coupee 9th District Court file 1476). Elvira died shortly before 13 December 1855, the date on which Samuel petitioned to settle her estate. The succession file has an inventory of Elvira’s property dated 19 December 1855, and a 10 March 1856 account of the estate sale. It shows Joseph Moore purchasing the 650-acre plantation on the Atchafalaya River that had come to Elvira from James M. Grammer, and it also shows her husband Samuel K. Green buying two slaves Lace, aged 18, and Amie, aged 50, who had been left to Elvira by James M. Grammer (see also Pointe Coupee Conveyance Bk. 1856-1858, #4387, for a record of the sale of Elvira’s land).

The 1850 federal census shows Samuel and Elvira living in Pointe Coupee with their real worth reported as $5,500.[5] In addition to a son Albert (who would drown on 12 June 1854 aged 9)[6] and a daughter Cornelia Jane, the household contains Elvira’s siblings Clinton, Camilla, and Mary Ann — the Camilla Birdwell whom Samuel’s son Ezekiel would marry in three years. The 1850 federal slave schedule for Pointe Coupee Parish shows Samuel and Elvira with 11 slaves.[7]

Now the stage is set for what happened between Ezekiel S. Green and his father Samuel K. Green in 1856: on 5 March 1856 in Pointe Coupee Parish, Ezekiel filed suit against his father, claiming that he was the legitimate owner of eight or nine slaves that his mother Eliza Jane Smith had left to him, and that his father had taken possession of the slaves and was refusing to give them to his son (Pointe Coupee Parish 9th District Court file 1525). The court file for this case, which is extensive, is how I know some of the facts about these folks I mention above, as I tell you that I will explain later in more detail how I happen to know this or that.

And now the stage is set for me to continue the story of what I found when I discovered that Ezekiel S. Green and his wife Camilla Birdwell went to Angelina County, Texas, from Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana, in 1863, and how that discovery significantly alters what I had thought I knew about Ezekiel and Camilla — information I’ll share in my next posting.

[1]The murder is reported in Southern Sentinel (Plaquemine, Louisiana), 8 June 1850 (p. 2, col. 2); in Planter’s Banner (Franklin, Louisiana), 13 June 1850, p. 1, col. 1; and Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 12 June 1840, p. 2, col. 2. The Sentinel reported that, on the preceding Sunday, Alden Piper (who was living with Ives at this time) had shot and killed him in his front yard, and had taken off in a skiff up Bayou Grosse Tête with Ives’ slaves. The Banner reported that a passenger aboard the steamboat Meteorhad told the newspaper the preceding Friday that Capt. Ives had been shot that week near his house by a man having some connection with him in business, and with whom he had had a difficulty. The Picayune reports the same set of facts, calling Ives “an old and respectable citizen.”

The Sentinel for 15 June announces that Piper had been apprehended, and has a petition by the parish sheriff Henry Sullivan to administer the estate of Samuel Ives (p. 2, col. 1; p. 3, col. 6). On 6 July 1850, the Sentinel reports with indignation that Piper had been released on $3000 bail (p. 2, col. 2).

On 11 July 1850, Sullivan petitioned to sell the movables and slaves of Samuel Ives’ succession (Iberville Succession Bk. O, p. 491). TheSentinel of 13 July reports that the succession sale was to be held on 23 July at Ives’ Mill on Bayou Sorel. The estate included 75 head of cattle, hogs, an ox, a cart, furniture, and the three slaves, who were to be sold on 12 Aug. (Sentinel, p. 2, col. 6). The Sentinel of 7 September 1850 (p. 2, col. 1) notes that a true bill had been found against Alden Piper by the Grand Jury, and that Piper had been granted a change of venue, and would be taken to Pointe Coupee Parish for trial at the fall term, commencing 16 Sept.

An Iberville Parish conveyance record notes that the slaves Tom, Ben, and Ruffin had been bought by Joshua Baker of St. Mary Parish. The conveyance record is a notice filed by Ira Mason of Port Chester in the town of Rye, Westchester Co., New York, to announce that he was attorney for Samuel Ives’ heirs (Iberville Conveyance Bk. 2, #413; filed 10 Apr. 1852, with P.C. Orillion and Zenon Labaure as witnesses).

A 4 March 1857 Iberville Parish conveyance record states that Mason had sold the land of Samuel Ives, and names the heirs: Emily, Mason’s wife; Bryan and Sarah Richards, Bristol, Hartford Co., Connecticut; Harry and Abigail Henderson of Bristol; Lydia Roberts, Hartford, Connecticut; Josiah C. and Ruth Nolan of Farmington, Hartford Co., Connecticut; and Justus H. and Esther Potter of Plymouth, Litchfield Co., Connecticut. The conveyance record indicates that, on 21 August 1850, the heirs had filed suit against Henry Sullivan in Iberville Parish (Iberville Parish Conveyance Bk. 4, #487; wit. C.A. Roth and Joseph H. Balch).

[2]See Steven Deyle, Carry Me Back: The Domestic Slave Trade in American Life (NY: Oxford UP, 2005), p. 99. According to Edward Baptist, The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism (NY: Basic Books, 2014), Austin Woolfolk of the Eastern Shore of Maryland established this business with his younger brother John, buying slaves in Maryland in agricultural areas no longer thriving to send them to New Orleans for sale (p. 179). Samuel was a younger brother of Austin.

[3]On the Adaes settlement and fort, see Betje Black Klier, “Pavie in the Borderlands,” in Pavie in the Borderlands (Baton Rouge: LSU Press, 2000), pp. 21-2); and Gary B. Mills, The Forgotten People: Cane River’s Creoles of Color (Baton Rouge: LSU, 1977), p. 1.

[4]The land’s history is traced in Llano County, Texas, DB T, pp. 53-4. There is not a comprehensive index to conveyances in Orleans Parish for 1839; the index for each individual conveyance volume in this time range has to be searched. I’ve done a partial, but not thorough, search of the index of Orleans Parish conveyance books in this period, without locating the original deed — though I actually have a copy of the original conveyance record from the Texas state land file for this tract of land, as the image of the document above shows you.

[5]1850 federal census, Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, p. 37 (dwel. 644/fam. 644, 5 September).

[6]See Times-Picayune (New Orleans), 13 July 1854, p. 2, col. 3, reporting (from the Pointe Coupee Echo) that Albert B., son of Major Samuel K. Green of Pointe Coupee Parish, had drowned the day before while crossing a bayou in a ferry flatboat in Saint Landry Parish. He was aged 9 years.

[7]This slave schedule is unpaginated. It shows Samuel and Elvira’s slaves enumerated on 6 September.

3 thoughts on ““The Reputed Father of a Child … Will Not Be Permitted Afterwards to Bastardize Such Issue”: The Case of Ezekiel Samuel Green (and His Father Samuel Kerr Green) (1)”