I also noted that I’m motivated to undertake this project because it was clear to me as I was growing up that my father, who was wounded slightly in the attack at Pearl Harbor, his brother, who earned a medal for bravery, my mother’s brother, who captured an SS officer and was on the scene of the Gardelegen massacre soon after it happened: these men of the previous generation knew full well that they were fighting to turn back the tide of fascism. I often think these days, as fascist movements rear their ugly heads again globally (and in my own nation), and as mendacious attempts are made to present fascistically distorted images of what constitutes good, brave soldiers, of how appalling what is taking place now would have been to the men of my family who served in World War II and hoped that their bravery had thwarted fascism decisively.

It becomes more and more clear to me that family members of the generation before me who served in the Second World War were extraordinary people, quiet heroes who never boasted about what they had accomplished during the war, and who, in fact, rarely spoke about their war experiences. I do know how deeply my own father was invested in the drive to conquer fascism and how he viewed his war experiences in that light from an incident that happened when I was fourteen or fifteen years old. In a fit of boredom in school, I idly sketched several swastikas in the back of my school notebook. These meant nothing at all to me, and I have no idea why it occurred to me sketch that particular figure.

Some time after this, my father happened to see these sketches in my school notebook and he became enraged. He shouted, “I fought to conquer people who cherished that horrible symbol. How dare you glorify it!” Why he imagined I had drawn the swastikas because I was pro-Nazi, I have no idea: I drew them idly, out of boredom. But this event taught me something: it taught me how much my father had invested personally — along with his brother, his brother-in-law, and my mother’s brother and half-brother — in defeating fascism in World War II. The quiet heroism of all these men — as well as the many women who served in the military and assisted the war effort in so many ways — deserves to be remembered, and this is why I’m recording and sharing these memoirs.

In each memoir, I’m speaking primarily to a family audience. As I shared in the posting yesterday that’s linked at the top of this posting, I am drawing up these World War II memoirs to share with my nieces and nephews. Some of the information and allusions in these memoirs are probably family-specific and may be of little interest to non-family members. I’m sharing the memoirs just as I am writing them for my nieces and nephews. On the other hand, perhaps it’s a good thing to create social histories of each of these World War II veterans, to provide detailed information about their backgrounds, families, and lives both before and after the war. My memoir of my father’s brother Carlton follows:

Henry Carlton Lindsey (1918-1988): A World War II Memoir

My father’s older brother Henry Carlton Lindsey was born 3 January 1918 at Coushatta, Red River Parish, Louisiana, the son of Benjamin Dennis Lindsey and Vallie Snead. When oil deposits were discovered in south Arkansas in the 1920s, my grandparents Dennis and Vallie moved with their children Carlton, B.D. Jr. (my father), and Helen to Union County, Arkansas, where the three children grew up for the most part. My grandparents made this move because they had been barely eking out a living farming in northwest Louisiana, where they both were raised, and the oil boom in south Arkansas opened up paying jobs for many people.

At some point around 1930, my grandfather was injured doing oilfield work and the family moved back to Red River Parish in the period 1930-4. They then returned to Arkansas where my father and his siblings graduated from high school in Union County, and by 1942, my grandparents had moved to Little Rock, not long after my father enlisted in the Marines on 6 March 1941. Helen Blanche was in nursing school at Warner Brown Hospital Nursing School in El Dorado. Carlton remained at home with his parents when they made the move to Little Rock, and the city directory for Little Rock in 1942 shows Carlton and his parents living together with Carlton working as a clerk in U.S. Employment Service.

At some point prior to my grandparents’ move to Little Rock, it appears Carlton had enlisted in an Army program for Flying Cadets. I gather this from an announcement printed on 25 December 1940 in the Fort Smith, Arkansas, newspapers Times Record and Southwest American. The announcement states that several Army Flying Cadet candidates were being directed to report to the recruiting office in the federal building in Little Rock the following Friday. The five candidates named included Carlton Henry Lindsey of El Dorado. As we’ll see in a moment, Carlton apparently had an interest in serving in the Air Force during WWII, though I have not found evidence that he actually enlisted in that branch of service.

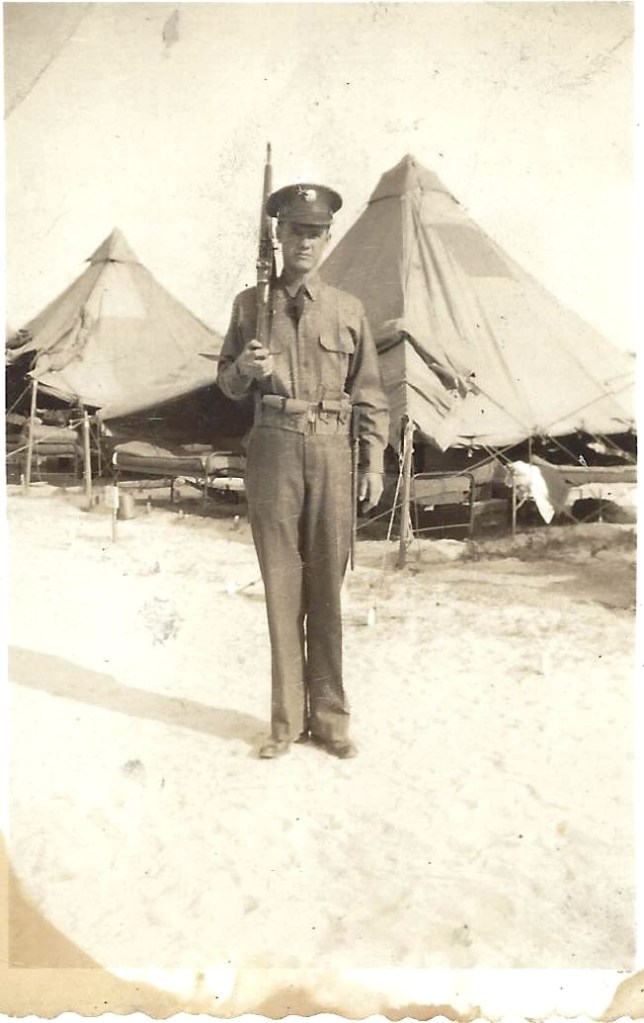

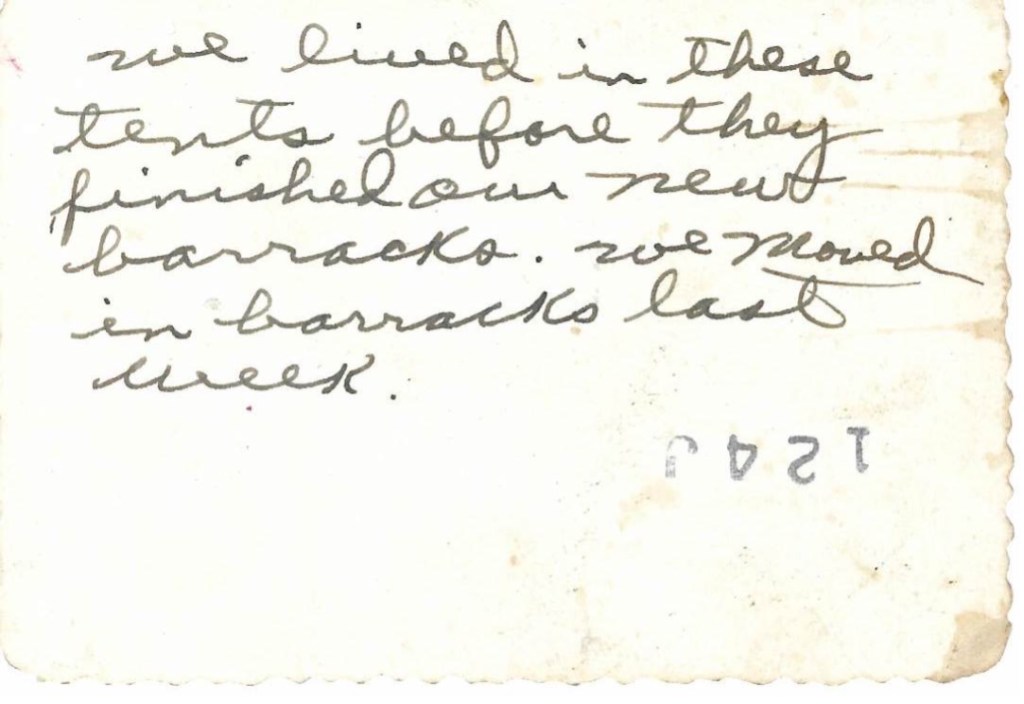

A letter my father sent his parents on 21 August 1941 from Pearl Harbor, where he was stationed aboard the USS Pennsylvania, was sent to his parents in Little Rock via his brother Carlton, since Carlton was living with his parents at the time. Early in 1942, on 25 February, Carlton enlisted in the Army. His enlistment record says that he had completed two years of college and was working as a clerk at “a general office.” His Army serial number was 17013810. The enlistment papers say that he was 71 inches in height (5’9”+) and weighed 134 pounds.

From this point forward throughout the war, I have scant information about Carlton’s experiences in World War II. As with other men in my family who were in military service during the war, he never talked about what happened to him in the war. My father and his brother were not very close and we saw this uncle and his family infrequently, though in the 1960s they lived not far from us: we were in El Dorado, Arkansas, and they in Arkadelphia some seventy miles away. For whatever reason, my mother nurtured hostility to my father’s family and did all she could to keep us apart from that side of our family, so that also accounted for my not having received much information about this uncle’s time in the war.

I should add that I always found my uncle Carlton a very genial, courteous, interesting man, a wonderful storyteller and mimic. Along with his wife Natille, he spent his professional years as a college educator and in Carlton’s case, an administrator. Carlton’s doctorate, which he earned in 1962 from University of Denver, was in speech and drama and he chaired drama departments at several colleges and universities, publishing a number of plays.

I thoroughly enjoyed being part of get-togethers of my father and his brother and sister. All three were entertaining storytellers, and Carlton (with his interest in theater) and Helen Blanche were wicked mimics. Both could do their mother, who had amusing quirks in both what she said and how she spoke, to a T. The three siblings enjoyed each other’s company and there was lots of laughter and story-telling when they got together. Carlton and my father were both accomplished wordsmiths. When my father spent time in Wisconsin in the CCC program prior to the war, CCC paid for him to take classes at Marquette University. He used to talk about a Jesuit priest who taught English there, and who encouraged my father to take up a writing career after my father wrote for a class assignment an entertaining account of growing up in south Arkansas during the oil boom.

Carlton had a strong interest in family history and compiled a history of our Lindsey family as a project for a class at Centenary College in Shreveport, the well-ranked college at which he studied for two years before joining the Army in 1942. He always freely shared family information with me and would no doubt have shared information about his war experiences if I had thought to ask him more.

What I do recall him talking about was his time in England, where he was stationed before his Army unit was shipped to Europe as the war progressed. He thoroughly enjoyed being in England, traveling around the country as much as his leaves would permit. I remember his saying that he met many people there who reminded him so much of his Snead relatives in Louisiana, people who were eccentric, funny, with a dry, sly, wicked sense of humor and a gift for language and music. Carlton’s first cousin Walter Alexander Lindsey was stationed in England during the years Carlton was there and in 1944 married an English wife, but whether Carlton and he were able to see each other in those years, I’m not sure.

From the little bit I ever heard about Carlton’s time in the war, he was involved in military campaigns in which American soldiers were sent from England into the Low Countries to liberate them from Nazi occupation and control. I know that some of these missions had him in the Netherlands at some point, since I recall hearing that he went back at least twice after the war to visit friends he had made in the Netherlands while he was serving in these campaigns.

At some point in these campaigns, it appears he did something distinguished, since a biography of Carlton published in Who’s Who in America, 1980-1 states that he had been awarded a Bronze Star with an oak leaf cluster for bravery. This award could only have been given for his service in World War II, since he didn’t serve in subsequent wars. From what I’ve been told, on the campaigns in Belgium and the Netherlands, Carlton served as a cartographer, a map reader who helped his military unit plot where it was heading as it marched into Europe.

Though Carlton had enlisted and served in the Army, he evidently had an interest in joining the Air Force and at some point must have spent time in the Air Force. I know this because a letter my father wrote to his brother Carlton on 15 August 1942 from Pearl Harbor — my father was still there aboard the USS Pennsylvania —states that my father was thinking of his brother (whom he addresses as “dear Bud”) because Carlton was to take exams on that day to get back into the Air Force. The letter was addressed to Carlton at Hdqrs. Det. 2nd Btn., 117th Infantry, Fort Jackson, South Carolina.

This detail, the address on the letter my father sent to his brother in August 1942, provides important documentary information. It tells us that Carlton was in the 2nd Battalion of the 117th Infantry, the so-called “Break-Through Regiment” that was housed under the National Guard. The 2nd Battalion of the 117th Infantry served in Normandy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Germany, and was engaged in the Battle of the Bulge in Belgium in December 1944 and January 1945. The 117th Infantry suffered heavy losses during this part of the war, with 26,038 casualties including 3,435 deaths in the period from June 1944 to May 1945. It appears that at some point as he served in the operations in Belgium and Holland, Carlton earned his medal for bravery.

From 4-12 September 1944, the 117th Infantry was in Belgium, having advanced there from France, and on 14 September 1944, it liberated Maastricht in the Netherlands, the first city in that country to be liberated from Nazi rule. Altogether in the month of September 1944, the 117th traversed approximately some 300 miles as it marched through the Low Countries from France, heading to Germany, and it captured 528 prisoners of war during that month. In December 1944 and January 1945, the 117th took control of La Gleize and St. Vith in Belgium. These historical details about the movements and actions of the 117th during World War II match what I remember hearing growing up about Carlton’s involvement in the military campaign to liberate Belgium and the Netherlands from Nazi domination.

My father’s letter to his brother on 15 August 1942 cited above, in which he says that Carlton was taking qualifying tests for the Air Force, also says that my father hoped to take tests to join the Naval Air Force, and that he had had a letter from their sister Helen Blanche asking him to write her boyfriend in Alaska. This was Lee Compere, son of E.L. Compere, an adjutant general of the Arkansas National Guard whom Helen would marry in January 1944. My uncle Lee wrote detailed memoirs of his WWII experiences and gave me a copy of these memoirs.

Though I don’t think Carlton moved from the Army to the Air Force during World War II, his interest in the Air Force continued following the war. His Who’s Who biography mentioned above says that he served as an education specialist for the Air Force from 1956-8 and chaired the speech department of Georgetown College in Kentucky, an Air Force college, from 1958-1961. The biography mentions, too, that in 1980, Carlton was a retired lieutenant colonel of the Air Force.

A newspaper clipping I have from the Brownwood [Texas] Bulletin dated 10 October 1974 announces that Henry C. Lindsey had resigned as academic vice-president and v-p of continuing education at Howard Payne College in Brownwood to take a position as educational specialist with the Community College of the Air Force at Randolph Air Force Base in San Antonio. The article mentions that he was a lieutenant-colonel in the Air Force and had had a reserve assignment with the admissions program of the Air Force Academy for the past fifteen years.

As this article demonstrates, in his professional life, my uncle went not by his middle name, Carlton, the name his family (except for his wife Natille) always called him, but by his first name Henry. He was named Henry after his grandfather Henry Clay Snead. His aunt, my grandmother’s youngest sister Grace Snead, suggested the name Carlton for him. Grace, who lived with my grandparents after my great-grandmother Lucy Frances Harris Snead died in 1919 and whom my grandparents put through nursing school, was reading a novel featuring a character named Carlton when her nephew was born, and because she fancied the name, she pressed her sister Vallie to name her first-born son Carlton.

Carlton was discharged from the Army on 27 October 1945. The discharge is recorded in Pulaski County, Arkansas, Index to Military Discharges, p. 79, and in the Army Register of Discharges Bk. 6, p. 174. After he returned from the war, Carlton went to Ouachita Baptist College (now University), earning a B.A. in 1948 soon after he married the daughter of the pastor of First Baptist Church in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, Evelyn Lovie Natille Pierce, who also graduated from Ouachita. In 1951, he earned an M.A. degree from Louisiana State University, and as I mentioned above, in 1962 a Ph.D. degree from University of Denver. From 1952 forward, he taught and did administrative work at a number of colleges and universities, with his wife Natille, who had a master’s degree in English, teaching that subject in the same institutions.

At some point either prior to or just after the war, Carlton, my father, and their brother-in-law Lee Compere all attended Little Rock Junior College, now University of Arkansas at Little Rock. None of them graduated from that institution, but I remember hearing them talk about being there at the same time, and about my father and Carlton living together in a boarding house in Little Rock as they went to school at the junior college.

I tend to think the time my father, his brother, and brother-in-law spent together at Little Rock Junior College was right after the war ended. Carlton and my father would have lived in a boarding house in Little Rock because my grandfather had bought a store at Sheridan thirty-five miles south of Little Rock during the war and my grandparents were living there when the war ended. While they were living in Sheridan, my grandmother worked at Pine Bluff Arsenal during the war, and it was due to their move to Sheridan, with a stint in Redfield where my mother was born and grew up, that my parents met. They met after Carlton had met my mother’s sister Pauline in a Baptist young adult group in Pine Bluff and had shown an interest in her. He then turned his attention to the Reverend Alton Pierce’s daughter Natille, whom he married in December 1947.

I have vivid memories of the last time I saw my uncle Carlton. At some point not long before his death in the hospital at Texarkana, Texas, on 30 April 1988, I drove from New Orleans, where I was living, to rendezvous with my aunt Helen and uncle Lee so that we could visit Carlton in the hospital. I think at this point, Carlton was in the hospital at Atlanta, Texas. He and Natille moved there after both retired from their teaching jobs in San Antonio. After Natille’s father Reverend Pierce died in 1964, Natille’s mother Lovie met and married a first cousin of my grandfather, Mark Jefferson Lindsey. Mark lived in Atlanta, Texas, and Carlton and Natille moved to Atlanta following their retirement so they could be close to Mark and Lovie.

Both Helen and Carlton developed serious adult-onset diabetes in midlife, and by 1988, Carlton had been seriously ravaged by that disease. He was hospitalized early in 1988 in Atlanta because he was having one tiny stroke after another, temporarily losing sight after each stroke. Helen and Lee and I wanted to visit him because it was clear to us (and to Natille) that he didn’t have much longer to live.

I remember him lying in the hospital bed, wan and gaunt and clearly struggling to speak. Even so, when we came into the room, he lit up, and the time we spent standing by his bedside talking to him was full of laughter and stories as he and Helen reminisced and enjoyed each other’s company. Then we left and walked into the hospital hallway, and Helen collapsed onto a bench and covered her face with her hands, sobbing painfully. I held her in my arms and she said, “It hurts so much to see him this way. He won’t live much longer.”

I knew that her years of nursing work gave her a special ability to understand what was happening medically to patients, so I took her word about that seriously. Carlton then grew worse and was sent to the hospital in Texarkana, where he died at the end of April. I am so grateful that I had an opportunity to see him that last time not long before his death. And it was so typical that when he and Helen saw each other, though he was very weak and confused, they still laughed and told funny stories and enjoyed being with each other.

5 thoughts on “A Series of WWII Memoirs (2): Henry Carlton Lindsey (1918-1988)”