Questions about How Samuel and Elvira Acquired Their Pointe Coupee Parish Land

But I have found no reference to Samuel or Elvira in the Pointe Coupee Parish vendee index. In the past, I had concluded that Elvira must have acquired this Pointe Coupee land from the estate of her first husband James Madison Grammer, who seems to have died between their marriage in Marshall County, Alabama, on 17 January 1838 and 1840, when it’s clear to me that Elvira is one of the females aged 15-19 living in the household of her parents James and Aletha Leonard Birdwell in Natchitoches Parish when the 1840 federal census was taken.[2] I think it’s unlikely that James M. Grammer came to Louisiana with Elvira and her parents. I suspect he died in Marshall County, Alabama, not long after the couple married and that, when the Birdwell family came to Natchitoches Parish from Alabama in 1840 shortly before the census was taken in Natchitoches Parish, Elvira accompanied her parents as a young widow.[3]

I say all this to note that I’m revising a deduction I had shared in previous postings about Samuel and Elvira — namely, that she was a widow who had some wealth from James M. Grammer at the time Samuel K. Green married her. If James M. Grammer, who was a young man of twenty-six when he married Elvira in 1838, left her significant resources, I have seen no records indicating that fact. I think it’s highly unlikely that a young just-married man dying in north Alabama in 1838-1840 would have acquired a tract of land in central Louisiana before his death, especially when he had no family members living there and when his father John Grammer died around the time his son James did, also in Alabama.

Shortly after Samuel and Elvira made their move to Pointe Coupee Parish in 1848, Elvira’s father James Birdwell died in December 1849 in DeSoto Parish.[4] I find no mention in his succession records of land he might have held in Pointe Coupee Parish before his death, or any indication that his nine children inherited large resources from their father’s estate. All this is to say: it’s a mystery to me, still, how Samuel and Elvira acquired their large plantation in Pointe Coupee Parish, and why that land was sold as part of Elvira’s estate at the time of her death in 1855. Elvira’s succession record seems to me to show the couple’s joint holdings sold in their entirety, as if all were in Elvira’s name and not Samuel’s. Samuel, in fact, bought property at the succession sale. Perhaps he left Natchitoches Parish bankrupt and all of the family’s remaining holdings were then placed in Elvira’s name to safeguard them from creditors?

Despite his having lost his land in Natchitoches Parish due to his failure or inability to pay his mortgage on the land, Samuel did arrive in Pointe Coupee Parish with valuable resources. As a previous posting states, the 1850 federal census shows him with a real value of $5,500, and the federal slave schedule of the same year lists him as owner of eleven enslaved persons.[5] These are the enslaved persons (and their progeny) who had belonged to Eliza Jane Smith, of whom Samuel took possession when Eliza Jane died at his house in March 1843. Perhaps Samuel found a way to parlay his possession of these enslaved people, some of which he placed in Elvira’s succession at her death, into purchase of a tract of land (in Elvira’s name?) when he and his family moved to Pointe Coupee Parish in 1848? The slave schedule shows these eleven enslaved persons, all listed as black, as a female aged 48, a male aged 26, a male aged 24, a male aged 22 a female aged 21, a male aged 20, a male aged 17, a female aged 15, a male aged 5, a female aged 4, and a male less than a year old. As the posting linked earlier in this paragraph also states, living with Samuel and Elvira and their children in 1850 were as well Elvira’s siblings Camilla and DeWitt Clinton Birdwell, the former of whom Samuel’s son Ezekiel would marry in 1853.

Even after Samuel and Elvira moved their family to Pointe Coupee Parish in or just after 1848, Samuel appeared in a lawsuit in Natchitoches Parish. On 3 December 1850 in that parish, he filed suit for debt against M.F. Carter, administrator of A.H.F. Duke.[6] The petition Samuel filed on 3 December 1850 states that he was late a citizen of Natchitoches Parish and was now a citizen of Pointe Coupee, and had been a creditor of Henry F. Duke, deceased, in the sum of $114. On 20 January 1848, Samuel had come into possession of a note Duke had made to Samuel’s father-in-law James Birdwell dated 3 November 1847. It was the money Duke owed to James Birdwell that Samuel was seeking to recover. The case file has the original promissory note of Duke to Birdwell, co-signed by Henry P. Welsh, who was discussed in the previous posting. The petition also states that a Mrs. Green was a creditor to Duke’s estate. I think this Mrs. Green must be a Mary Greene whose note for attendance upon an enslaved woman belonging to Duke is also in the case file. I know of no kinship connection Mary Greene may have had to Samuel K. Green.

Henry Duke is Henry Andrew Duke, who was born in Georgia about 1823 and died in Natchitoches Parish in 1848 not long after the Duke family moved there from Perry County, Alabama. The prior Perry County, Alabama, residence is noted in the case file.

Ezekiel S. Green vs. Samuel K. Green: Information about Pointe Coupee Parish Years

In a number of previous postings, I’ve already told almost all else I know about Samuel K. Green’s years living in Pointe Coupee Parish from 1848 up to right before his death in 1860 in Grimes (now Waller) County, Texas. Those previous postings are as follows:

Ezekiel Samuel Green (1824/5 – 1900/1910) (1)

Ezekiel Samuel Green (1824/5 – 1900/1910) (2)

Mary Ann Green (1861-1942) and Husband Alexander Cobb Lindsey (1)

As these linked postings indicate, much that can be discovered about Samuel’s years in Pointe Coupee Parish is found in affidavits in the lawsuit his son Ezekiel filed in that parish against his father on 5 March 1856, in Ezekiel’s complaint setting that case into motion, and in the legal rulings in this case in both Pointe Coupee Parish and at the level of the Louisiana Supreme Court.[7] As several of the linked postings indicate, Ezekiel’s 5 March 1856 complaint states that when his mother Eliza Jane Smith died at Samuel’s house in Natchitoches Parish (the date is given as on or around 13 March 1843 in several affidavits in the case file), he allowed his father to take possession of the enslaved persons left to Ezekiel by Eliza Jane, and Samuel then moved the family in an unspecified year to Pointe Coupee Parish, bringing with him the enslaved persons except for Hetty and two of her children, Eliza and Alfred, whom Samuel sold.

Ezekiel further stated that he had permitted Samuel

as his father to take possession of his mother’s succession from parental affection and believed that he would act a father’s part towards him, and never entertained the slightest idea that the said Green would contradict or contest his will to said succession.

Samuel had persistently told Ezekiel, the complaint states, that he knew that the enslaved persons were Ezekiel’s property and that he, Samuel, had guardianship of them only until Ezekiel had come of age. But after he married Elvira Birdwell Grammer and she died, Ezekiel’s complaint maintains, Samuel then

manifested a disposition to sell and dispose of said slaves as his own property for the ultimate benefit and advantage of his children by his last wife, to the great detriment and infamy of your petitioner’s rights.

Ezekiel had asked his father for two or three years prior to filing his lawsuit in 1856 (note Ezekiel’s marriage to Camilla Birdwell in 1853) to surrender the enslaved persons to him, and since his father refused to do this and gave indications of intending to sell the enslaved persons and keep the money from the sale for himself and his remaining child by Elvira, Cornelia Jane —Albert had died by 1856: see below — Ezekiel filed suit to secure his claim to ownership of the enslaved persons, to force Samuel to recognize him as Samuel and Eliza’s legitimate son, and to obtain recompense for Samuel’s use of the enslaved persons after he refused to turn them over to his son.

Albert’s Death Followed by Elvira’s

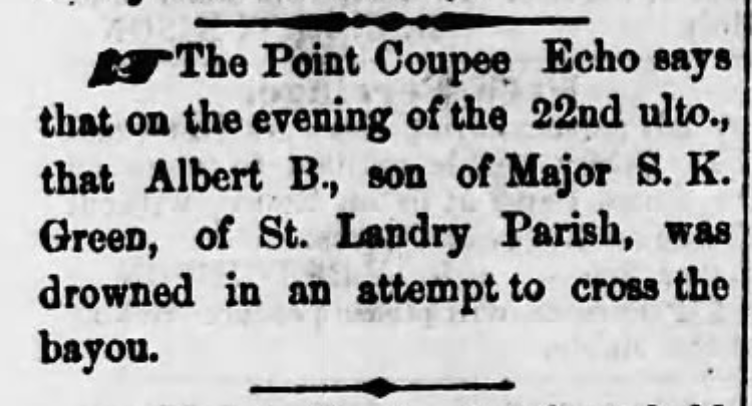

Less than two years before Ezekiel initiated his lawsuit against Samuel in March 1856, Samuel and Elvira’s son Albert drowned. On 13 July 1854, the New Orleans Times-Picayune published a detailed account of Albert’s death, which occurred in St. Landry Parish on 22 June, noting that it had picked the account up from the Pointe Coupee Echo.[8] The Daily Gazette and Comet of Baton Rouge also reported the drowning on 12 July 1854, also crediting the Echo as its source.[9]

The detailed story told by the Picayune states that Albert B. Green, the son of Major S.K. Green of Pointe Coupee Parish, “a fine promising youth of nine years old,” had drowned on the 22nd ult. in a bayou in the parish of St. Landry as he was attempting to cross the bayou on a ferry flat boat. The current in the bayou was strong and the rope pulling the ferry across the water had caused Albert to fall into the water. One of his schoolmates, Parris Dickery, had valiantly jumped into the bayou and tried to save Albert, but failed to do so.

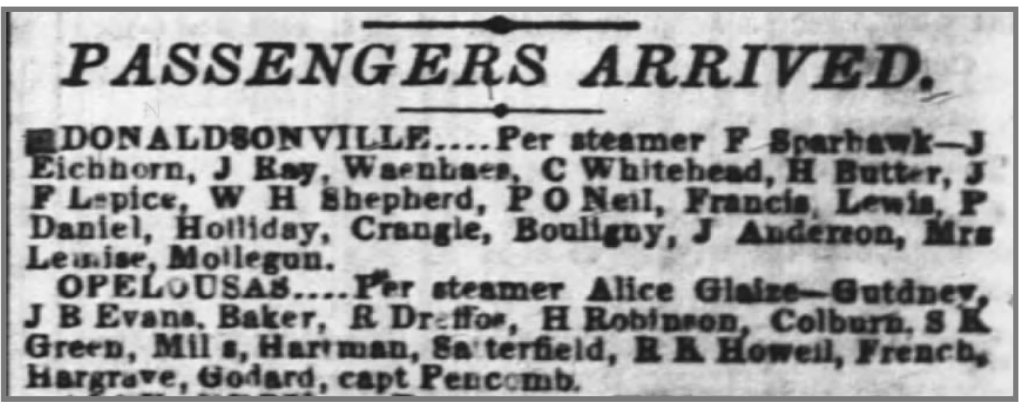

As several of the linked postings in the list above state, Opelousas is the parish seat of St. Landry Parish, and Ezekiel S. Green spent time living there in the latter part of his life. His father Samuel seems to have had some connection to St. Landry Parish during his years living in Point Coupee: on 17 February 1855, the Times-Picayune carried a list of passengers who had just arrived at Opelousas aboard the steamer Alice Glaize.[10] The list includes S.K. Green.

The year 1855 was a year of multiple family deaths for Samuel K. Green. On 2 November 1855, his mother Jane Kerr Green died in Bibb County, Alabama. Samuel K. Green is listed as her son and one of her heirs in her estate documents in Bibb County, and when her estate was settled by her son James Hamilton Green, with whom she spent her final years, on 23 November 1857, Samuel received his share of the $514.85 divided among Jane’s heirs (Bibb County, Alabama, Probate Minutes Bk. F, pp. 411-413).

As a number of the linked postings in the list of links above indicate, Samuel’s wife Elvira died in Pointe Coupee Parish at some point prior to 13 December 1855, when Samuel petitioned in that parish for administration of her succession.[11] The petition states that Samuel and Elvira had one minor child living at the time of Elvira’s death, their daughter Cornelia Jane, for whom Samuel was appointed tutor and T.A. Miller was appointed under-tutor.

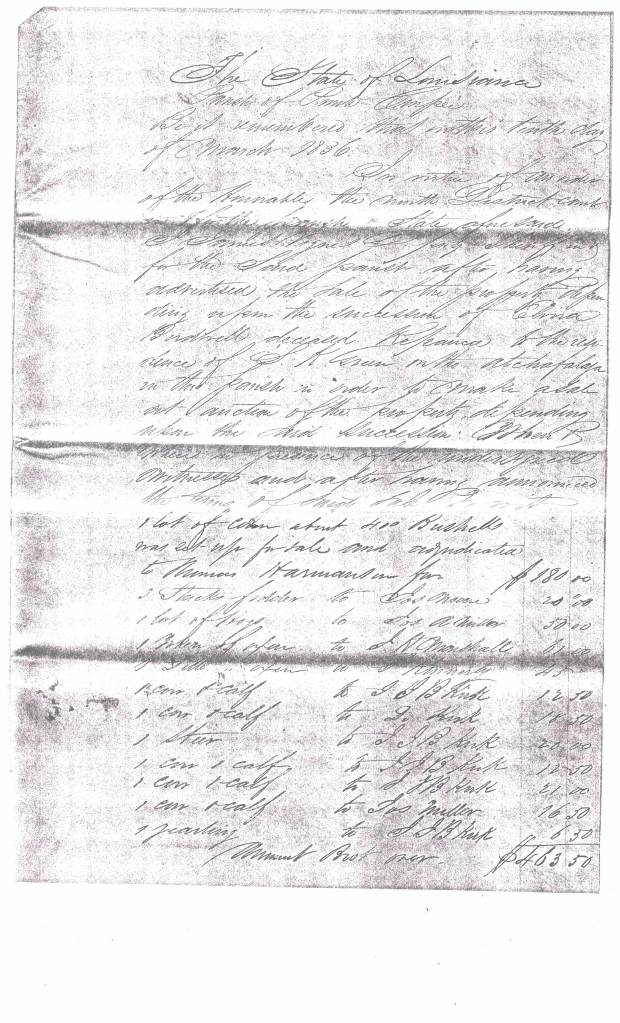

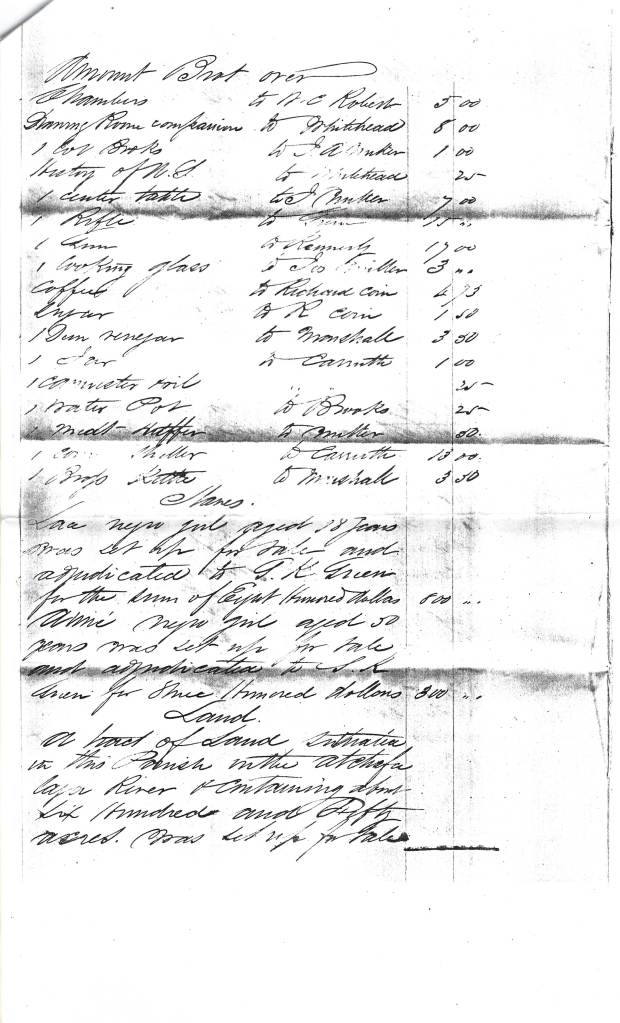

On 12 January 1856, Samuel petitioned for a family meeting, noting in his petition that Elvira’s property had been inventoried on 19 December 1855. In addition to Samuel, the family meeting was comprised of Elvira’s brother Thomas Birdwell and family friends Thomas Hamilton Anderson, Hilary Calahan, T.T. McRae, and N.L.C. Fulton. At the family meeting held on 24 January, it was agreed that the land and enslaved persons belonging to Elvira would be sold. Samuel then filed a petition to homologate on 26 January.

It was after this on 5 March 1856 that Ezekiel filed his lawsuit against his father. The immediate precipitating factor for that filing was evidently Samuel’s intent to sell all or some of the enslaved persons of whom Ezekiel claimed ownership, with Samuel representing Elvira as the owner of the enslaved persons.

On 10 March 1856, Elvira’s estate was sold, and as I state above, it seems to me that the entire joint holdings of Samuel and Elvira were sold at the estate sale, with the exception of most of the enslaved persons whom Samuel was still keeping from his son. Buyers of farm and household items included Joseph A. Miller, J.H. Marshall, Joseph I.B. (Ignatius Benjamin) Kirk, Reason Cripps (who gave bond with Ezekiel S. Green on 2 January 1853 for his marriage to Camilla Birdwell, William Means, and T. Harmondson. Included in the sale were enslaved persons Amie and Lace, aged 50 and 18, whom Samuel bought from the succession for $800 and $300. As a previous posting explains, there’s clear documentation that Amie belonged to Ezekiel’s mother Eliza Jane Smith, who purchased her in New Orleans on 10 May 1829, and I’m fairly sure that Lace is an enslaved girl named as Lady in the will Eliza Jane made at Samuel’s house in Natchitoches Parish on 5 March 1843.[12] These enslaved persons did not belong to Elvira, and Samuel was engaging in some sleight of hand in placing them in Elvira’s succession, a sleight of hand designed to allow him to claim ownership of them by purchasing them.

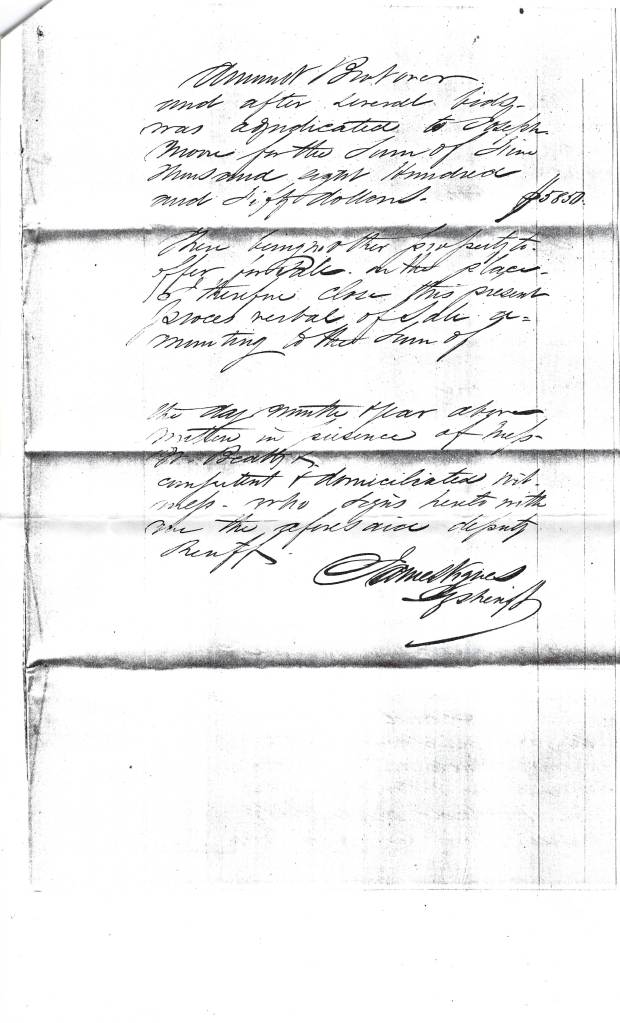

In addition to these other items, the couple’s 650-acre plantation along the Atchafalaya River was sold to Joseph Moore for $5,850, close to the amount of Samuel’s real worth of $5,500 on the 1850 federal census, as noted above. The conveyance document for this land sale shows that the 650 acres lay in sections 37 and 38 of township 2, range 7 east.[13] This land lies about five miles down the Atchafalaya River from Simmesport and across the river from Odenburg, both towns in Avoyelles Parish, though the land Samuel and Elvira owned was in Pointe Coupee.

Green vs. Green Ends with Verdict in Favor of Ezekiel

Minutes for Pointe Coupee’s 9th district court state on 14 April 1856 that Samuel K. Green had failed to respond to a summons issued to him to appear in court, and so judgment was rendered by default in the Green vs. Green case in favor of Ezekiel as plaintiff.[14] Subsequent notations in this court minute book show that Samuel K. Green then responded with a petition for a continuation of the case, and at this point, Ezekiel filed an amended petition. On 22 April, Samuel filed his answer to Ezekiel’s amended petition and the case was continued. Court minutes note on 24 April 1856 that Samuel had been required to give bond and the enslaved persons of whom he was claiming ownership had been sequestered, because he was trying to sell them.[15]

A 21 April 1856 affidavit of Ezekiel in the Louisiana Supreme Court case file for this lawsuit explains why this sequestering was ordered: Ezekiel’s affidavit explains that while the Green vs. Green suit was underway, Samuel took nine of the enslaved persons of whom he claimed ownership from Pointe Coupee Parish to New Orleans and tried to sell them. Ezekiel followed and had the enslaved persons sequestered in New Orleans.[16]

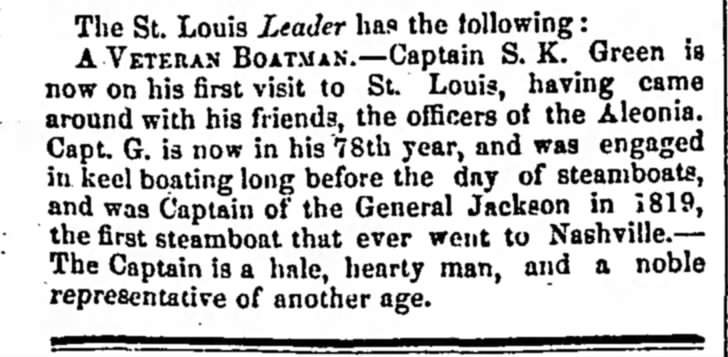

As his legal battle with Ezekiel was underway, Samuel up and went to St. Louis for reasons not explained in a newspaper notice I’ve found noting this trip. On 23 May 1857, the Tennessean of Nashville picked up a notice from the Leader of St. Louis that Captain S.K. Green, “a veteran boatman,” was on his first visit to St. Louis, having come with friends who were officers of the steamboat Aleonia.[17] The notice states that Samuel was in his 78th year (he was actually 67 by my reckoning), had been a keelboat man prior to the coming of the steamboat, and had been captain of the General Jackson in 1819, this being the first steamboat to come to Nashville. The article states, “The Captain is a hale, hearty man, and a noble representative of another age.”

As a number of the linked postings in the list above also indicate, on 10 August 1857, Samuel received title to the 640 acres in Llano County, Texas, he had purchased in New Orleans on 10 January 1837 from Hansford Cophendolpher. The land came to Samuel in August 1857 through a Bexar County, Texas, bounty land grant to Cophendolpher assigned to Samuel.

Samuel K. Green appears to have been still living in Pointe Coupee Parish on 13 January 1858 when he appealed the verdict of the Pointe Coupee Parish court against him to the Louisiana Supreme Court, with John B. Evans and James H. Cason as his principals. On 28 January 1858, Samuel’s lawyers W. Beatty and W. Cooley filed a brief with the Supreme Court answering Ezekiel’s petition to that court. This brief unequivocally states that the full maiden name of Ezekiel S. Green’s mother was Eliza Jane Smith.[18]

On 17 January 1859, the Louisiana Supreme Court handed down a verdict at New Orleans in favor of Ezekiel. The verdict notes that his father’s attempt to bastardize him “came with a bad grace” since “it is sometimes impossible for a child to know with certainty whether he be legitimately begotten or not.” Moreover, the court decided, the fact that Samuel had introduced Eliza Jane Smith and Ezekiel S. Green to the world as his wife and son made it impossible for him to deny paternity of Ezekiel.[19]

On 29 January 1859, the Pointe Coupee Democrat published the Supreme Court decision.[20] On 12 February, the same paper then published a notice that Samuel K. Green had appealed the Supreme Court decision and his appeal had been denied.[21]

Samuel Dies and Is Buried in Grimes (now Waller) County, Texas

The January 1859 Supreme Court verdict does not indicate where Samuel K. Green was living at the time this verdict was rendered. The last record I have for him is his listing on the 1860 mortality schedule in Grimes County, Texas, which states that he had died of pneumonia in that county on March 1860 (p. 5, no. 32). This document gives S.K. Green’s age as 70 and states that he was born in South Carolina. He appears to have been with the family of his brother Benjamin S. Green in Grimes County at the time of his death. Benjamin died of heart disease in Grimes County in the same month, according to the mortality schedule. B.S. Green’s death listing is next to Samuel K. Green’s on the mortality schedule.

Samuel and Benjamin are buried in a family cemetery in what is now Waller County with Benjamin’s children Benjamin S., Thomas L., John W., and Lucinda C. Green. This cemetery is about halfway between Magnolia and Hempstead, Texas, on Joseph Road south of farm-to-market road 1488 very close to the borders of both Grimes and Washington County. According to Waller County’s Historical Commission in its Directory of Cemeteries in Waller County, in 1977 the cemetery was on W.B. Holder’s land, from the J.A. Padillo survey, “BB and Cab 98.”[22]

I visited this Green family cemetery on 3 July 2011. At that time, there was no marker indicating that there was a small family cemetery beside the road. The area seemed to be under development as a housing area. The one stone for B.S. Green, his second wife M.M. Green, and their children was lying on the ground, and the stone for S.K. Green also appeared to have been on the ground until not long before I visited the cemetery. At that time, I could still see the indentation behind this grave marker showing where it had been lying on the ground.[23]

It appeared to me in July 2011 that someone had recently placed S.K. Green’s marker back on its foundation. These markers all have only names, no dates, with initials for the given names, and decorative motifs around the top and bottom of the stones. The markers for both Samuel’s grave and that of Benjamin and his wife and their children are in the same style.

Did Samuel marry again after Elvira died? If so, I have been unable to find a marriage record. On 20 February 1856, the Times Picayune reported that Mrs. S.K. Green and child were in New Orleans staying at the City Hotel.[24] Samuel did, of course, have a nephew, the son of his brother Ezekiel Calhoun Green, who had the same name, but that Samuel Kerr Green did not marry until 1859.

Then on 27 July 1882 and 1 August 1882, the New Orleans Times Democrat published a curious notice: the notice was by William L. Thompson of San Antonio, who stated that he was seeking to find the widow of Samuel K. Green of Point Coupee Parish, who had married a printer in New Orleans following Samuel’s death.[25] On 7 October 1882, the same paper published a notice saying that a gentleman in New Orleans was seeking to contact the widow of Samuel K. Green formerly of Pointe Coupee Parish, who had married a printer in New Orleans.[26] Following this, on 6 March 1886, the Pointe Coupee Banner published a notice from the Hon. W.L. Thompson which stated that Samuel K. Green or his heirs could hear something to their advantage by applying to Thompson at San Antonio.[27]

I have been unable to find any information about a wife of Samuel K. Green subsequent to Elvira Birdwell Grammer, but these notices definitely tempt me to think that he remarried at some point following Elvira’s death — and that his widow then remarried a printer in New Orleans. If so, I wonder if the child mentioned in the Times-Picayune hotel notice in February 1856 was Samuel and Elvira’s daughter Cornelia Jane, and what became of her. I have not been able to find a record of her following her mention in her mother’s Pointe Coupee Parish succession record.

[1] Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, Succession file no. 1476.

[2] Marshall County, Alabama, Marriage Bk. 1838-1848, p. 32; and see the bond James M. Grammer signed on 17 January with Bazel R. Starnes as bondsman, the license he received on the same date, and the return of George Long, j.p., stating that he married the couple on the 18th, all in the loose-papers marriage files of Marshall County, available digitally at FamilySearch. And see 1840 federal census, Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, p. 172. The census entry spells James’s surname as Burdwell.

[3] The 1840 date for the Birdwells’ move from Alabama to Louisiana is stated in an 1883 manuscript entitled “Biography of the Leonards,” compiled by Thomas Dunlap Leonard and Joseph J. Gill. Thomas Dunlap Leonard (1810-1888) was the son of Robert Leonard and Rachel Dunlap and was a first cousin of James Birdwell’s wife Aletha Leonard, whose parents were Thomas Lewis Leonard and Sarah M. Lauderdale. Joseph J. Gill (1816-1902) was the husband of Angelina Moore, daughter of Hannah Leonard and William D. Moore. Hannah was a sister of Robert and Thomas Lewis Leonard. Thomas Dunlap Leonard wrote this Leonard (and Birdwell) family history, with Joseph J. Gill adding material after it was completed. I have not been able to pinpoint the whereabouts of the original copy of “Biography of the Leonards.” I have a typescript copy sent to me in 1997 by Jackie Leonard of Tanner, Alabama. Thomas Dunlap Leonard compiled this manuscript while living in Waco, Texas, where he died 30 September 1888. He grew up in Lincoln (later Marshall) County, Tennessee, knowing his grandparents Thomas Leonard (1752-1832) and Hannah Elizabeth James (1752-1842) and recording their information about the early generations of the Leonard (and Birdwell) family. The last record I find of James Birdwell in Marshall County, Alabama, was his sale of land to John Kirkland there on 30 November 1839 — see Marshall County, Alabama, Deed Bk. B, p. 55-6. The deed and James and wife Letha’s acknowledgment both state that James and Aletha were in Madison County when they sold this Marshall County land.

[4] DeSoto Parish, Louisiana, Succession file no. 159; and Desoto Parish, Louisiana, Succession Bk. D, pp. 643-650. The 1850 mortality schedule for DeSoto Parish, Louisiana, shows James Birdwell, a planter, aged 54, born in Georgia, dying on cholera in December 1849 (p. 168). On 6 December 1849, the New Orleans Crescent reported that “cholera is prevailing quite generally in New Orleans”: “Rumors of Cholera in New Orleans,” New Orleans Crescent (6 December 1849), p. 2, col. 2. Typically, cholera traveled up and down river systems, so if New Orleans, on the Mississippi River, was experiencing a cholera outbreak in December 1849, it’s not surprising to discover that cholera was also manifesting itself at the same time in parishes along the Red River further north in Louisiana. On 15 December, the New Orleans Times-Picayune reported that cholera had appeared on plantations along the Red River and was present in Madison, Carroll, and other parishes in north Louisiana: “Health in the Country and City,” Times-Picayune (15 December 1849), p. 2, col. 1.

[5] 1850 federal census, Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, p. 37 (dwelling/family 644, 7 September); and 1850 federal slave schedule, Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, unpaginated, 6 September.

[6] Samuel K. Green vs. M.F. Carter, administrator of A.H.F. Duke, Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, District Court case file no. 4326, bundle 190.

[7] Ezekiel S. Green vs. Samuel K. Green, Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, 9th District Court, file no. 1525; Ezekiel S. Green, Appellee, vs. Samuel K. Green, Louisiana Supreme Court Docket no. 5483; E.S. Green v. S.K. Green, Louisiana Supreme Court file no. 1521; and A.N. Ogden, Louisiana Reports, Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Louisiana, vol. 65: For the Year 1859 (New Orleans: West, 1860), p. 3.

[8] Times-Picayune (13 July 1854), p. 2, col. 3.

[9] Daily Gazette and Comet (Baton Rouge) (12 July 1854), p. 2, col. 1.

[10] “Passengers Arrived,” Times-Picayune (17 February 1855), p. 3, col. 7.

[11] See supra, n. 1.

[12] Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana, Record Bk. 34, p. 130 (no. 3422).

[13] Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, Conveyance Bk. 10 October 1856-5 February 1858, no. 4387.

[14] Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, District Court Minute Bk. Bk. E, p. 1063.

[15] Ibid., p. 1088.

[16] Ezekiel S. Green, Appellee, vs. Samuel K. Green, Louisiana Supreme Court Docket no. 5483, pp. 23-4.

[17] “A Veteran Boatman,” Tennessean (23 May 1857), p. 3, col. 1.

[18] Ezekiel S. Green, Appellee, vs. Samuel K. Green, Louisiana Supreme Court Docket no. 5483.

[19] Ogden, Louisiana Reports, Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Louisiana, vol. 65: For the Year 1859, p. 3.

[20] Pointe Coupee Democrat (29 January 1859), p. 1, col. 1.

[21] “Decisions of the Supreme Court,” ibid. (12 February 1859), p. 2, col. 3.

[22] Waller County, Texas, Historical Commission, Directory of Cemeteries in Waller County (Brenham: Hermann, 1977).

[23] See Find a Grave memorial page of Samuel Kerr Green, Green cemetery, Hegar, Waller County, Texas, created by A Noboby, maintained by Annette Stone-Kerr, with a tombstone photo by A Nobody.

[24] “Arrivals at the Principal Hotels Yesterday,” Times Picayune (20 March 1856), p. 6, col. 3.

[25] Times Democrat (New Orleans) (27 July 1882), p. 5, col. 3, and (1 August 1882), p. 5, col. 5.

[26] Ibid. (7 October 1882), p. 9, col. 4.

[27] Pointe Coupee Banner (6 March 1886), p. 3, col. 5.

One thought on “Samuel Kerr Green (1790-1860): The Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, Years and Death in Grimes County, Texas (1848-1860)”