I heard a number of stories about Powell’s heroic death as I was growing up. From 1950 forward, my family lived in El Dorado in south Arkansas, the town in which my uncle Lee and his brother Powell grew up, and in which their parents were living as I came of age there. Some of what I was told about Powell’s death came from conversations my mother, who was very fond of Lee and Powell’s father General E.L. Compere, had with General Compere and then told me about. I’ve now also verified and documented these stories with research.

Powell Butler Compere was born 18 October 1918 in Hamburg, Ashley County, Arkansas, son of Ebenezer Lattimore Compere and Emma Lucille Hawkins. As my previous posting about his brother Lee says, in 1931, the Compere family moved to El Dorado, which was in south Arkansas as Hamburg also was. E.L Compere had a law practice in El Dorado and had been made a brigadier general in 1929. During the war years and for some time afterward, he headed the Selective Service system of Arkansas.

As my posting about his brother Lee indicates, Powell was the second of E.L. Compere and Lucille Hawkins Compere’s three sons. Prior to his enlistment in the Army, Powell made quite a mark as a brilliant student at El Dorado High School and then El Dorado Junior College, and finally at University of Texas Austin. In high school, he was part of a prize-winning debate team of El Dorado High in the 1930s. The team traveled to a number of places around the country while Powell was part of it, competing in and winning debates. When he entered El Dorado Junior College, he was elected vice-president of his class in his first year there, 1936-7.

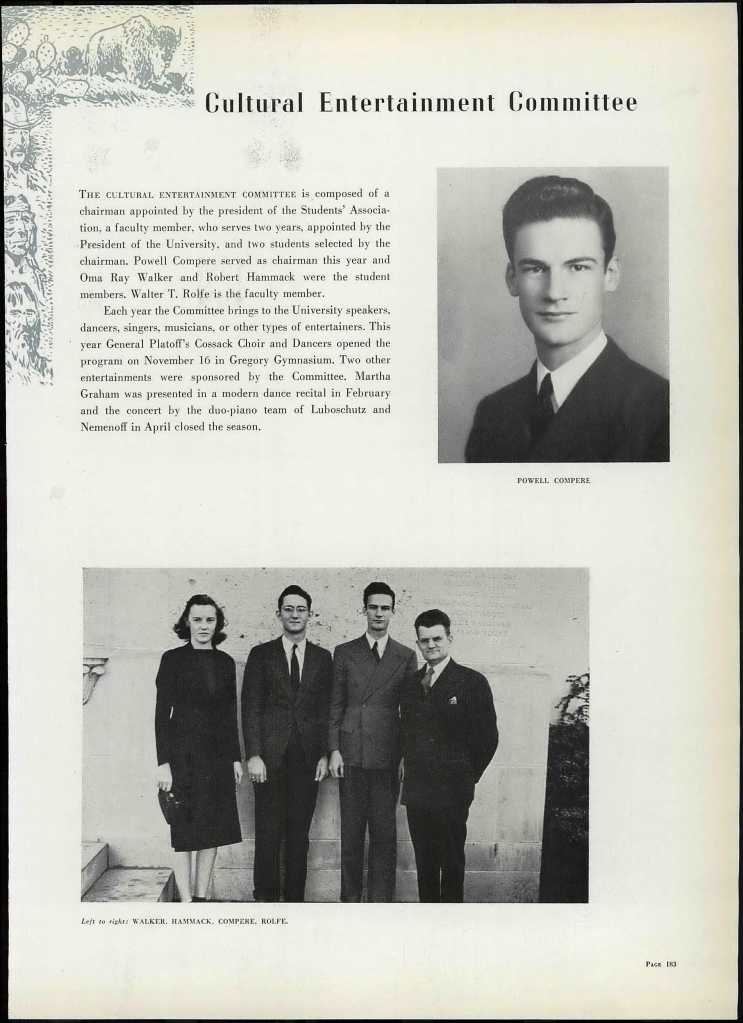

At University of Texas in Austin, where Powell was a pre-law student majoring in economics and political science, he was a Dean’s List honor student, and was actively involved in the cultural and theatrical life of the university. In his second year at UT, the Student Association appointed him chair of the school’s Cultural Entertainment Committee. In his final year there, Powell chaired the building committee for the construction of the school’s first co-op housing, Campus Guild, a project begun in 1937 and completed in 1941.

As his brother Lee’s manuscript entitled “My Memoirs — 2000: An Autobiography of Lee H. Compere” (2000) notes, Powell attempted to enlist in the Army while he was still studying at University of Texas, but his enlistment was deferred until he had completed his degree and had graduated. Lee states, “He was then drafted in the state of Arkansas and inducted at Camp Joseph T. Robinson in North Little Rock. He remained there, working in the classification section of the personnel in the reception center.”[1]

Powell’s enlistment papers show him enlisting at Camp Robinson on 6 May 1942, giving his occupation as “actors and actresses” and noting that he had completed four years of college.[2] He was 73 inches in height — a little over 6 feet — and weighed 139 pounds.

Lee Compere’s memoirs state,[3]

He was transferred to Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri and subsequently assigned to the language school at Washington University in St. Louis, Mo. Upon graduation from that school, he was promoted to sergeant and assigned to the 44th Division, later to be sent to France.

Dad continued his duties as Director of Selective Service for the State of Arkansas for the duration, plus, of the war.

As my posting about Lee’s WWII experiences notes, following Lee’s marriage in El Dorado on 8 January 1944, Lee and his bride Helen Blanche Lindsey traveled to St. Louis, where Lee was stationed temporarily en route to his enrollment in the Army’s Signal School at Fort Momouth, New Jersey, and while they were in St. Louis, they spent time with his brother Powell. This was the last time that Lee saw his brother. In speaking of this meeting early in 1944, Lee says,[4]

My brother, Powell, had been selected to receive special training in the ASTP (Army Specialized Training Program) at Washington University in St. Louis, and his assignment was to study the language and customs of the people of France and Germany, especially emphasizing German.

We were able to visit with him one day, and met him in the coffee shop at the train station. We caused many raised eyebrows while enjoying our coffee and visit, as, since Powell was in the university, he was not required to have insignia or unit designation on his uniform, he merely had the plain, unmarked uniform on. I had my uniform on, fully identifiable by my ADC (Alaska Defense Command) shoulder patch, which was not readily recognized by civilians, my sergeant stripes, service bars eight bars, one for each six months of service), and green piping on my service cap, etc.

When anyone was near our table, Powell would lower his voice, speak to us in German, draw pictures on the napkin and act somewhat elusive. Eventually, we all got up and left, and as soon as we were out of the door, several people grabbed the napkin that Powell had written on, only to find that he had left a note to them that he and all of us were legitimate soldiers and thanking them for being so observant. I am sure that everyone thought that we were spies or ‘5th Columnists.’

We had previously, before arrival in St. Louis, received a letter from Powell written entirely in German. We were able, in St. Louis, to find a civilian businessman to translate the letter for us.

He studied it quite extensively and finally asked who wrote it. When I told him that it was from my brother, he complimented him to me, stating that the letter was written in ‘High German’ and by a highly educated person, congratulating us on our marriage and on his having a new sister-in-law.

Our meeting in St. Louis was the last time that we saw Powell, as he was assigned to Co. K, 324″ Infantry, 44th Division, 7th Army and sent overseas to France. He was killed in action during the ‘Battle of the Bulge’ in eastern France, on January 5, 1945, and classified as a ‘hero’ by all of his comrades in his unit for his action to save certain civilians that he had been associated with on the German border.

Lee then notes that his brother Powell was killed in action in France during the Battle of the Bulge on 5 January 1945, and he got word of his brother’s death and burial at Epinal, France, soon after he arrived in the Philippines early in 1945.

The Battle of the Bulge was the last major German offensive operation on the Western Front. As the handwriting was on the wall that Hitler’s days were numbered and Germany was going down in defeat with Allied troops advancing through France, the Netherlands, and Belgium, liberating those nations from Nazi control, Hitler chose to mount one last desperate campaign to turn the Allies back. In northeastern France, as a sub-operation of the Battle of the Bulge, Hitler launched Operation Nordwind to try to push the Allies out of Alsace where they had made important inroads.

Powell’s death occurred at Frauenberg is in northeastern France on the German border a few miles south of Saarbrücken. In his book Marching Home: To War and Back with the Men of One American Town, Kevin Coyne describes what happened.[5] Coyne notes that American troops had reached Frauenberg before January 1945 and for several days had been trying to rid the town of German soldiers hiding in houses in towns and villages of that part of France. The American troops were under fire from those hidden soldiers as well as German troops just across the border in Germany.

Early on 5 January 1945, with Powell Compere leading his fellow soldiers on foot as tanks shielded these foot soldiers, Powell, who spoke very good German, walked towards a house from which German soldiers who were holed up in the house were firing, and asked them to surrender. Several German soldiers had been captured and/or surrendered by this point. The goal of Powell and his comrades was to try to save the lives of civilians in various houses in Frauenberg including those commandeered by German soldiers.

Coyne writes,

“Come out and surrender!” [Powell Compere] called in German. Some civilians were still holed up in adjacent houses, and the Americans didn’t want to sacrifice either them or the homes of the neighbors who had fled. He was hoping the Germans would realize they were finished, and would end their stand before anyone else had to die.

Compere called again, but no answer came from the house. As he turned to walk back, several windows brightened with muzzle flashes.

“Look out behind you!” someone yelled, but he was already lying facedown in the street, dead.

The Americans shot back with a furious barrage that made clear their intention to stay right where they were until the Germans were gone. The tanks boomed, and the soldiers stole toward the house that Compere had died trying to spare. Within an hour, nine Germans were prisoners, and a dozen were corpses. Two more Americans died, too, including Lieutenant Thompson, killed by a bazooka shell as he searched for one of his men.

A history of the Army’s 324th Infantry in which Powell served notes that he had patrolled the village of Frauenberg prior to this engagement with the German soldiers and the officers of the troops then planned the attack in which Powell was killed early on the morning of 5 January, using Powell’s information to plot their route.[6] Powell acted as the troops’ guide during the attack. This source notes that the soldiers involved in the attack were from the 3rd Platoon of K Company and part of C Company.

As an article about Powell’s death published in several Arkansas newspapers on 19 January 1945 states,[7]

Sergeant Compere was with the 324th Infantry 44th Division of the Seventh Army and had been overseas since September, 1944.

His division was in action at Forêt de Parroy, Bois de la Garenne, Avincourt, Sarrebourg and Saverne Gap, and was cited by Lt. Gen. Alexander M. Patch, commander of the Seventh Army for outstanding accomplishments.

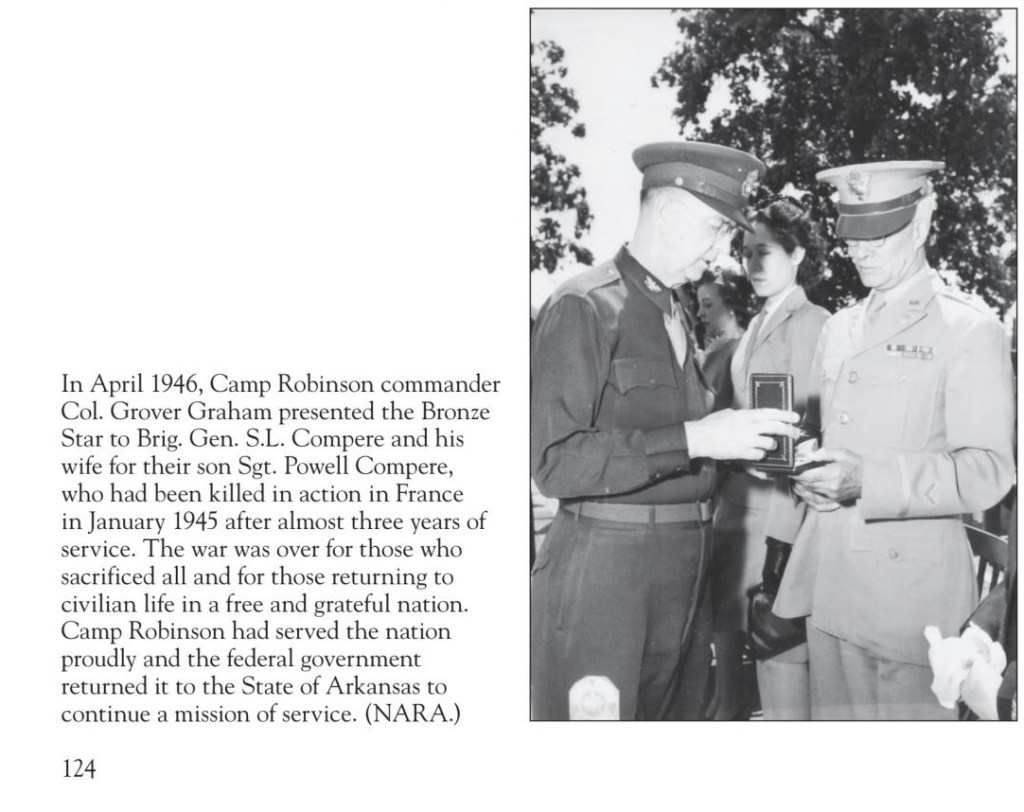

Powell was posthumously awarded a Bronze Star for bravery and a Purple Heart for the sacrifice of his life, with his father General Compere receiving the Bronze Star at Camp Robinson on Powell’s behalf in April 1946.[8]

In his memoir, Powell’s brother Lee writes,

I had stated earlier that Helen and I had visited with my brother Powell in St. Louis, Missouri during early 1944 while he was in language school there as ASTP (page 111), and that that short visit was the last time that we would see him, as he was killed in action during the ‘Battle of the Bulge’ on January 5, 1945.

I wish to digress now to further explain that my progenitors, the ‘First Generation of the Compere family’ were two small waifs, orphans of the French Revolution, who were befriended by an English cobbler, a Mr. Job Fox, traveling through the Alsace-Lorraine area of eastern France during his annual buying trip for ‘fine’ leather.

Since they did not know their family names, and as their parents had been beheaded by the king as Huguenots during the Massacre of St. Bartholomew in 1572, Mr. Fox attempted to adopt them, but English law would not allow him to do that, as they were ‘foreign born.’

He did not know what to call them, but since they had been calling him their ‘Compere’ he decided to name them that name. It was later determined that ‘Compere’ was French, not for ‘Godfather’, but for ‘Special Godfather,’ a Godfather chosen by the child, not one chosen by the parents.

From all records, it has been determined that these two children were natives of the Alsace-Lorraine province near the eastern boundary of France with Germany.

All records of my brothers’ death indicate that he was killed in very close proximity to where these two children were found by Mr. Fox.

A large military cemetery near the city of Epinal, France was established for American soldiers killed during that time and until the end of the war in Europe, and Powell was buried there.

Soon after my arrival in the Philippines, I received word of his death and burial there in Epinal.

After the cessation of the war in both Europe and the Pacific, it was decided by the War Department – ‘Graves Registration,’ to close the cemetery at Epinal. Dad and Mom were advised that Powell’s body would be moved to the American cemetery in Northern France, but we all agreed with Dad and Mom that, as long as he was buried at Epinal, we were satisfied that he was buried very near where our family originated, but, with the word that he would be moved from that area, we all agreed that he should be brought ‘Home.’

He was reburied with full military honors in the family plot at El Dorado, Arkansas on August 7, 1948.

An obituary published in the Shreveport Journal on 7 August 1948 notes Powell’s reburial in El Dorado and that a funeral service was held for him at First Baptist church in El Dorado prior to his burial with military honors in Arlington cemetery.[9] I recall my mother telling me that a member of the McRae family of south Arkansas, Thomas Christopher McRae, son of Thomas Chipman McRae, assisted the Compere family in getting information about Powell’s death and burial in France immediately after these events occurred. There was a period of time in which the Comperes had difficulty receiving information, and Thomas C. McRae assisted them in finding information. He was particularly helpful because he had ties to the federal government from his years serving as his father’s secretary in Washington, D.C., when the elder Thomas C. McRae represented Arkansas in the House of Representatives.

[1] “My Memoirs — 2000: An Autobiography of Lee H. Compere,” p. 75.

[2] NARA, US, WWII Army Enlistment Records, 1938-1946, box 1298, available digitally at Fold3.

[3] “My Memoirs — 2000: An Autobiography of Lee H. Compere,” p. 76.

[4] Ibid., p. 111.

[5] Kevin Coyne, Marching Home: To War and Back with the Men of One American Town (New York: Penguin, 2004), pp. 160-5.

[6] Army, 324th Infantry, Combat History Of The 324th Infantry Regiment, 44th Infantry Division (Baton Rouge: Army & Navy Pub. Co., 1946), p. 66.

[7] “Son of Gen. Compere Loses Life in France, The Sun (Jonesboro, Arkansas) (19 January 1945), p. 3, col. 5. Also published in Conway’s Log Cabin Democrat. See also “Sgt Powell Butler Compere” at Find a Grave’s memorial pages for Arlington cemetery, El Dorado, Arkansas, created by Sandra.

[8] Ray Hanley, Camp Robinson and the Military on the North Shore (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia, 2014), p. 124.

[9] “Sgt. P.B. Compere,” Shreveport Journal (7 August 1948), p. 12, col. 7.

2 thoughts on “A Series of WWII Memoirs (6): Powell Butler Compere (1918-1945)”