As the following posting will explain, there’s a big wrinkle in this story of the WWII service of my mother’s brother W.Z. aka Dub Simpson. Not long before he died, his sister insisted that he tell me the story of something that happened to him in Germany during the war. He told me in lavish, precise detail about being among the American troops that first arrived on the scene following the horrific massacre at Gardelegen in April 1945. What he told me perfectly matches what documentarians and historians of that event say about the massacre.

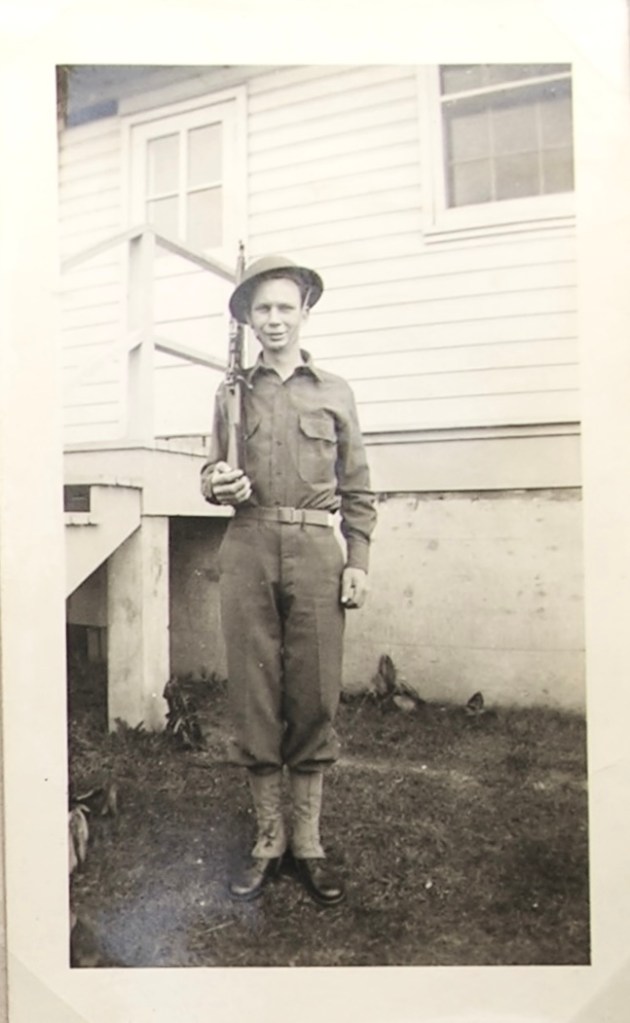

Yet a photo I have (above) of my uncle from his service years makes me fairly certain that he served in the 51st Engineers Combat Battalion, while it was the 102nd Infantry Division that came to Gardelegen just after the massacre occurred. I know of no way to square this circle than to conclude that a group of soldiers from the 51st may have been detached to accompany the 102nd for a period of time as both military units moved parallel to each other north and east through Germany to liberate it from Nazi control in 1945. Dub’s story follows:

William Zachary Simpson (1915-1999): A World War II Memoir

My mother’s brother William Zachary Simpson was born 23 November 1915 in Redfield, Jefferson County, Arkansas, son of William Zachariah Simpson and Hattie Paralee Batchelor. He was the only son of my grandparents Wm. Z. and Hattie Simpson. By his first wife Cora Harwell, who died as a result of childbirth, my grandfather had a son William Carl Simpson who was also a soldier in World War II and about whom I’ve written a memoir that I’ll share here soon.

William Zachary Simpson was a junior, though my grandmother, thinking that the old-fashioned name Zachariah sounded “country,” insisted on altering her son’s middle name to Zachary. Dub’s namesake, his father and my grandfather William Zachariah Simpson, was named for his grandfathers William H. Braselton and Zachariah Simms Simpson. The given names William and Zachariah run back many generations in the Braselton and Simms families. Zachariah Simms was the name of Zachariah Simms Simpson’s grandfather.

My uncle Wm. Zachary Simpson, who was called Brother by his family members and Dub or W.Z. by friends and acquaintances, was a retiring, rather shy and quiet, soft-spoken man, who did not often talk about his war experiences. Growing up with five garrulous sisters in a matriarchal household headed by my grandmother Hattie after my grandfather died in 1930, Dub may have had little chance to talk much. He was timid by nature, and stories I heard as a child said that my mother, Dub’s sister Clotine, who was more than a little combative and ready to fight at the drop of a hat, would come running if she saw another boy taunting or threatening her brother on the school playground, and she’d fight his fight for him.

Though Dub said little about his war experiences — and this was true of all the men in my family who served in World War II — he did talk a bit about being stationed in the Aleutian Islands. I think this was soon after his enlistment in 1941 and before his Army unit was deployed to Germany in the final part of the war. The Aleutians held strategic importance for the US, as a vantage point for monitoring Japanese military movements and protecting the northwest US, and battles were fought there in 1942-3 to keep them from Japanese occupation. A picture I have of him from his time in the Aleutians (above) shows him hugging a dog that was dear to him in this period of his service.

I do also know from stories I was told in my formative years that Dub captured an SS officer during the war. This was a story I heard family members tell frequently. He was in an Army unit that advanced into Germany from southwest Germany as the tide began turning in the war and the Nazis were placed on offensive. His Army unit was charged with liberating Germans from Nazi control as they advanced north and east through the country.

At some point in that operation, the story goes, Dub came on an SS officer who was hiding in a hut in the woods. The man was shaving when Dub found him. As Dub took him prisoner, he asked the SS man whether he had a gun. The man said he was unarmed, but when Dub did a search of the hut, he found a Luger pistol under the man’s mattress. As Dub took the Luger, the officer said that if the tables had been turned, he’d have killed Dub for lying to him. Perhaps that’s what he wanted Dub to do rather than to take him prisoner. Dub took the man prisoner and marched him back to camp and turned him over to American authorities.

Dub also brought the Luger home, and once or twice as I was growing up, I saw it. My brother Simpson was fascinated with it and with a small pearl-handled pistol that had belonged to our grandmother and was wild to see and hold both of these weapons. My grandmother kept them locked away in my grandfather’s old safe and refused to open the safe except once or twice, to slake Simpson’s thirst to hold the pistols.

Dub also brought back a swastika, a large banner or flag that I seem to recall he found hanging on a building and tore down: it had a large black swastika imprinted in a white circle with a red outer circle, the colors of the Nazi national flag. This swastika was folded and stowed away in a drawer in the sideboard in my grandmother’s dining room in my growing-up years, and we occasionally took it out to look at it. I remember feeling it somehow exuded evil when I looked at it or touched it. I wanted nothing to do with it.

Late in their lives, Dub’s older sister Katherine (Kat, we called her), with whom he lived many years to the end of his life, encouraged Dub to tell me about something that he had experienced during the war and about which he had never spoken to me. I think Kat realized that if they both died with Dub never having shared this story, this piece of history would be lost.

Dub told me that as it advanced into northern Germany, his Army unit came on the site of a gruesome massacre that had just taken place. I can’t say with absolute certainty that Dub told me this massacre had occurred at Gardelegen in Saxony-Anhalt east of Braunschweig, but my vague recollection is that he did identify indeed the place as Gardelegen. Everything he told me matches what histories of that massacre have recorded about it.

He told me that local citizens along with Nazi guards had taken prisoners they were safeguarding and locked them into a large barn and set the barn on fire. When Dub’s Army unit arrived on the scene, the ashes of the barn were still smoldering and there were burned bodies everywhere. Dub said that where parts of the barn remained, American soldiers (he included) could see that those being burned alive had clawed against the barn walls and doors trying to find a way out.

The well-documented massacre at Gardelegen took place on 13 April 1945. Knowing that American forces were marching through Germany liberating towns and villages from Nazi control and also setting those imprisoned by the Nazi regime free, SS officers along with local citizens took over a thousand prisoners under their control at Gardelegen, most of them Poles, shut them into a barn, and burned them alive. The prisoners were being held for evacuation to concentration camps at Bergen-Belsen, Sachsenhausen, and Neuengamme.

On 14 April, US Army troops from Company F, 2nd Battalion, 405th Infantry Regiment of the 102nd Infantry Division arrived in Gardelegen while the barn was still smoldering. The 102nd was nicknamed the Ozark division since historically it contained large numbers of men from Missouri and Arkansas. These American troops found bodies of 1,016 prisoners who had been burned alive, and found a few prisoners who had managed to escape. Within a few days, photographers from the Army Signal Corps arrived and documented the massacre in photos which then began appearing in the American press. On 19 April, both the New York Times and the Washington Post ran stories on the Gardelegen massacre, quoting a soldier who said,

I never was so sure before of exactly what I was fighting for. Before this you would have said those stories were propaganda, but now you know they weren’t. There are the bodies and all those guys are dead.

On 21 April 21, the local commander of the 102nd Division ordered some 300 men from the town of Gardelegen to give the murdered prisoners a proper burial. The American troops wanted local citizens to acknowledge their responsibility for the massacre, which had been engineered by SS officers but took place with the willing complicity and assistance of citizens of Gardelegen.

On 25 April, Colonel George Lynch addressed German civilians at Gardelegen, stating,

The German people have been told that stories of German atrocities were Allied propaganda. Here, you can see for yourself. Some will say that the Nazis were responsible for this crime. Others will point to the Gestapo. The responsibility rests with neither — it is the responsibility of the German people….Your so-called Master Race has demonstrated that it is master only of crime, cruelty, and sadism. You have lost the respect of the civilized world.

Everything Dub told me about what he saw fits all that was reported about the Gardelegen massacre, and I know that the Army unit in which he was serving was involved in marching north and east through Germany from the Rhine in southwest Germany to liberate Germany in 1945. But I’ve been unable to find documentation of the actual Army unit in which Dub served, and I suspect that documentation is now gone after a disastrous fire in 1973 at the National Personnel Records center in St. Louis destroyed a large percentage of World War II service records.

If you look closely at the World War II service photo of Dub at the head of these memoirs, you’ll see that he’s standing next to a plaque elevated from the ground which states, “HQ, 51st Battalion.” If that plaque indicates the military unit in which Dub served, then he may not have been in the 102nd Infantry, the Ozark Division, since, as far as I can discover, it didn’t have a 51st Battalion. Dub was perhaps in the 51st Engineers Combat Battalion of the Army, which took part in the Aleutian campaign and then was sent to Germany at the end of the war to help in the liberation of Germany from the Nazis.

It’s possible, of course, that Dub posed for that photo while visiting a military camp other than his own. It’s also possible that he was in an Army unit detached to participate in initiatives of the 102nd Battalion in 1945. The long and short of it is, I just don’t have precise documentation of the military unit in which Dub served, and I’ve concluded that it’s very likely some men in Dub’s Army unit were detached to serve with the 102nd at some point during the campaign to liberate Germany, in which both were involved, and this led to his being with the soldiers who arrived on the scene right after the Gardelegen massacre occurred. I do have the following documents that aren’t helpful in determining his World War II unit, but do provide information about him during the war:

Dub filed his World War II draft registration on 16 October 1940 at Redfield, stating the date and place of his birth and listing his mother as his contact person. The draft registration card says that he was working for F.G. Smart Motor Company in Pine Bluff, and was 5’9” tall with brown hair and gray eyes and weighed 135 pounds.

Dub then enlisted in the Army on 30 December 1941.

I have a letter that Dub sent on 5 March 1945 to his sister Pauline Simpson at 106 S. Cherry St. in Pine Bluff. The letter is addressed from Sgt. W.Z. Simpson 37102504, GFRC, New York, New York. This ground forces reinforcement center (GFRC) in New York was either at Camp Shanks near the New York port of embarkation or Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn. Dub was not actually there at the time he sent this letter, but the letter was processed there as it arrived from the front and this was Dub’s American Army address while he was overseas.

Because the letter was sent from the front, it was photographed by the V-Mail Service of the War and Navy Department, and Pauline received a photocopy and not the original letter. The letter notes that Dub was responding to a letter Pauline had sent him and was waiting for mail from home to catch up with him. Dub states that he was “somewhere in Belgium” and had been on pass several times. He found it interesting to watch the people in Belgium but frustrating that he could not communicate with them. Dub tells Pauline that he aments that he had not studied French in high school.

Dub sent another letter to Pauline on 12 March 1945 with the same posting address as found on his previous letter. Pauline was still living at 106 Cherry in Pine Bluff. This letter notes that Dub’s last letter to Pauline had been sent from Belgium, and that he was now “somewhere in Germany.” Dub speculates that he would remain in Germany till the war was over, which he hoped would be soon. Mail had still had not caught up to Dub, and he had not heard from his half-brother Carl, and was not sure where Carl was, except that the last letter Dub had gotten from his mother stated that Carl was in Italy.

A final story I heard growing up is that at some point as his Army unit advanced into Germany, Dub took a little German boy under his wing, and the boy became so fond of him that he began calling Dub “Uncle Willie.” As American soldiers liberated German cities, towns, and villages, they frequently gave out rations that had been inaccessible to most Germans for some years. Children, in particular, welcomed the chocolate bars and chewing gum that most American soldiers handed out freely to them. I think that the little German boy who became so attached to Dub may have first connected to “Uncle Willie” when Dub gave chocolate to him. I’m not sure why, but I have stuck in my head the recollection that this story was set in Wiesbaden in southwest Germany.

And those are the stories I was told in my growing-up years about the World War II service of my uncle Wm. Z. Simpson.

5 thoughts on “A Series of WWII Memoirs (3): William Zachary Simpson (1915-1999)”