Though none of these men of the generation before me spoke much about their experiences during the war, I did, nonetheless, hear stories told about those experiences. Family members talked and I listened. And if I don’t pass those stories on, find a way to record them, the chain will be broken and that oral history will die with me.

As I was thinking about this, I contacted my nieces and nephews to ask whether they’d like for me to write down what I remember hearing about the war experiences of my father and my uncles. Writing down these stories would, I pointed out, preserve them, and not only would my nieces and nephews be learning information they might want to know about their grandfather and great-uncles, they’d have the information to pass on their own children.

My nieces and nephews told me they’d very much like for me to compile World War II memoirs of these men of the generation prior to me. So I’ve been busy for weeks now working on this project, both trying to rack my brain to remember what I heard during my formative years, and also to try to find as much documentation as I might find to corroborate or add to the information contained in the stories.

I want to underscore that my elders who served in WWII never spoke much about their war experiences. My father was at Pearl Harbor when it was bombed and was wounded slightly by shrapnel from an exploding bomb. About that experience, he did talk, and he showed my brothers and me the scar on his abdomen. But about the rest of the war, in which he served as a Marine gunner in the Pacific theater, he refused to talk. And I suspect part of the reason for his silence was that he bore trauma from those years. I recall one instance when he had, as the Irish say, drink taken and was morose and sad. He broke into tears, a very rare thing for him, and said, “No one will ever know how that war scarred the men of my generation.”

In conclusion (I’m concluding this introduction, that is, to the posting that will follow), I’ve come to think of my father, his brother, and my uncles as quiet, unsung heroes whose willingness to risk everything in the fight against fascism in World War II deserves to be celebrated, their deeds remembered. My mother’s brother captured an SS officer and told in detail about being at the scene of the horrific massacre at Gardelegen, Germany, right after the massacre happened. My father’s brother, who took part in the liberation of Belgium and the Netherlands from Nazi rule, received a bronze star with an oak leaf cluster for bravery for his actions during the war. A brother of the brother-in-law of my father died a really heroic death in France as he put his own life at risk to try to save the lives of his fellow soldiers. All of this is what motivates me to write.

And now I’m going to start a series of postings in which I share the memoirs I’ve been composing for my nieces and nephews. This first one gathers the information and documentation I have regarding my father’s WWII service. In seeking documentation for all the memoirs in this set of WWII memoirs, I’m hampered by the fact that all of these men’s military service files burned in 1973 at the fire in St. Louis at the National Personnel Records Center. I am by no means an expert in researching military service records or the history of the American military during WWII, and may well be making quite a few mistakes in interpreting such information as I can find as I work on this project. If so, my apologies for any errors found in this series of memoirs.

Benjamin Dennis Lindsey (1920-1969): A World War II Memoir

My father Benjamin Dennis Lindsey was born 18 June 1920 at Coushatta, Red River Parish, Louisiana, the son of Benjamin Dennis Lindsey (elder) and Vallie Snead, about whom I’ve posted a bit of information in the past. The following is the memoir I’ve shared with my nieces and nephews:

On 6 December in 1941, my father went to sleep aboard the USS Pennsylvania, which was in dry dock at Pearl Harbor, not knowing that he’d be awakened early the next day by bombs that were being dropped on the American military ships in the harbor, and that he’d be wounded by shrapnel from a bomb that exploded on the Pennsylvania. That incident — what he experienced as Pearl Harbor was bombed — was the only part of his WWII years about which he ever talked.

He told my brothers and me repeatedly that when the bombing began, it was very early in the morning and he and his fellow soldiers were asleep and had no idea what was happening. The attack was a sneak attack that occurred with no warning. Along with other soldiers, he quickly jumped from his bunk, dressed, and ran to the deck of the ship where I think his duty was to operate a machine gun. At some point as the attack unfolded, a bomb exploded on or near the USS Pennsylvania and shrapnel from that pierced his abdomen. He was not seriously injured, but did have a scar that he showed my brothers and me.

P.S. On a purple heart award that my father apparently received due to being wounded at Pearl Harbor, see the addendum below.

I know next to nothing about my father’s experiences after this, during the war itself, except that he spent those years in the Pacific theater and its campaigns. I don’t have his military service papers, and do not think they survived the destruction of WWII records in the disastrous 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis. As I’ll note below, the address from which my father wrote his family in a letter he sent in 1945 suggests to me that he was in the 2nd Marines, a military unit that played an important role in the “island-hopping” campaign of the Pacific Theater to seize control of various Pacific islands from the Japanese.

Due to a DNA surprise in 2018, I began to try to piece together — at a micro level — the lives of my father and his siblings Carlton and Helen Blanche in the early 1940s, and found this task surprisingly difficult. We often don’t have abundant documentation of what our parents and their siblings were doing as they finished high school and launched their adult lives. We know in a vague sense what was taking place in their lives. But unless they have left us a cache of documents — high school diploma, college acceptance application, copies of first job contracts, etc. — we don’t know the details.

My father enlisted in the Marines on 6 March 1941 at Oklahoma City, with his enlistment papers stating that he was living at Sheridan, Arkansas. My grandfather, also named Benjamin Dennis Lindsey (my father was a junior), bought a store at Sheridan at some point not long after both of his sons had enlisted in the military for the war.

My father was honorably discharged at Camp Pendleton in Oceanside, California, on 1 November 1945. His separation papers state that he attended Sea School, and was a Lt. AAA Gun Crewman during the war. The papers also state that he had graduated from McRae High School in Mount Holly, Arkansas, and after that, worked as a derrickman in the oil fields of Delta Drilling Co., Tyler, Texas, from 1 November 1940 to 1 January 1941. The papers state that he intended to go to college, with an interest in English and journalism, and preferred to settle in south Arkansas, since he considered it home.

Mount Holly is in Union County, Arkansas, on the Arkansas-Louisiana border. My grandparents, who were barely eking out a living farming in Red River Parish, Louisiana, where they grew up and my father was born, moved their family to that county in the 1920s when oil was discovered there and jobs with good salaries were opening up. My father was raised there, hence his high school education at McRae High in Mount Holly, from which his siblings also graduated. The fact that Union County was an oil county would account for his taking a job with Delta Drilling in Tyler, Texas. I assume he graduated from high school in May 1938, since he was born in 1920 — and I may have the graduation program filed away someplace. At some point during the 1930s, he also entered the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and was sent to Wisconsin to do logging work. I know from stories he told my brothers and me that during that period, the CCC program paid for him to take classes at Marquette University in Milwaukee.

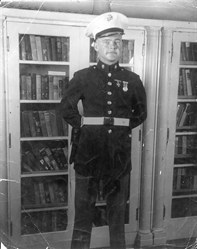

I have a picture of my father with his platoon, the 16th Platoon of the U.S. Marine Corps, taken at San Diego in April 1941. I also have a 21 August 1941 letter he sent to his parents from USS Pennsylvania, Marine Detach, c/o Fleet post office, Pearl Harbor, Q.H. The letter was sent via his brother Carlton, then living with their parents at 300 Center Street in Little Rock. By 1942, according to the Little Rock city directory, my grandparents had moved to 3023 Marshall Street, and their son Carlton was living with them and working as a clerk for the “US Emp Serv” (US Employment Service), according to the city directory. My Aunt Helen Blanche is not listed with her brother and parents in that 1942 city directory because she had entered the nursing school of Warner Brown Hospital in El Dorado, Arkansas, and was studying nursing there with the Sisters of Mercy who operated the hospital.

My father’s August 1941 letter to his parents states that he had been in port at Pearl Harbor for some time, and had gone to Honolulu, Waikiki, and Haleiwa on a liberty. He speaks of the beauty of the Royal Hawaiian Hotel and the beach at Waikiki, as well as of the large groves of palms loaded with coconuts. The letter ends with my father telling his family that after he had been on board about 3 months, he could take tests for private first class, which would increase his pay to $36 per month.

I have a number of photos of my father at this time, enjoying the beaches of Hawaii with other soldiers.

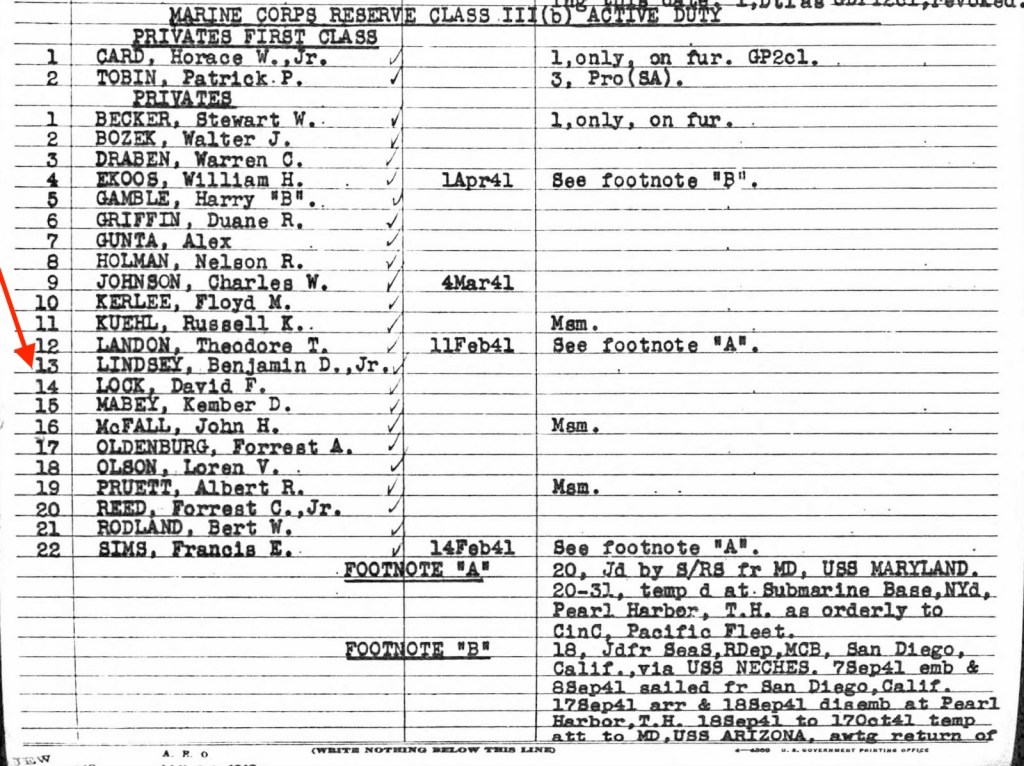

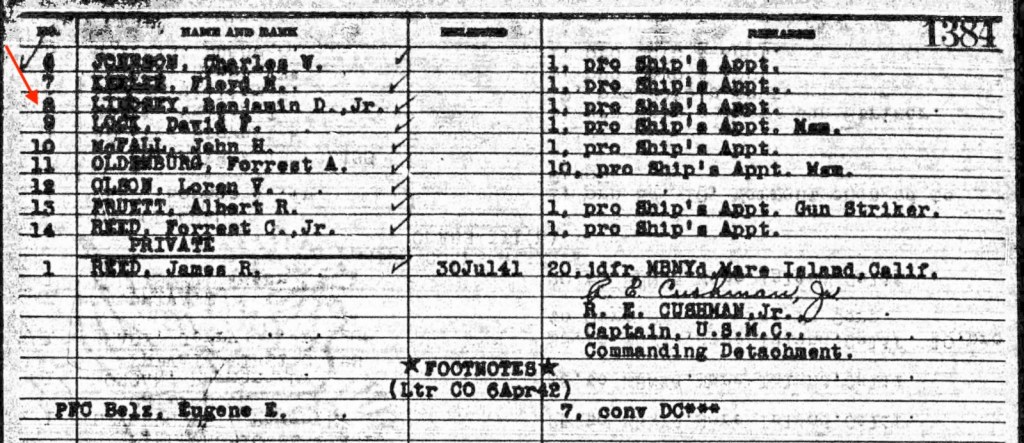

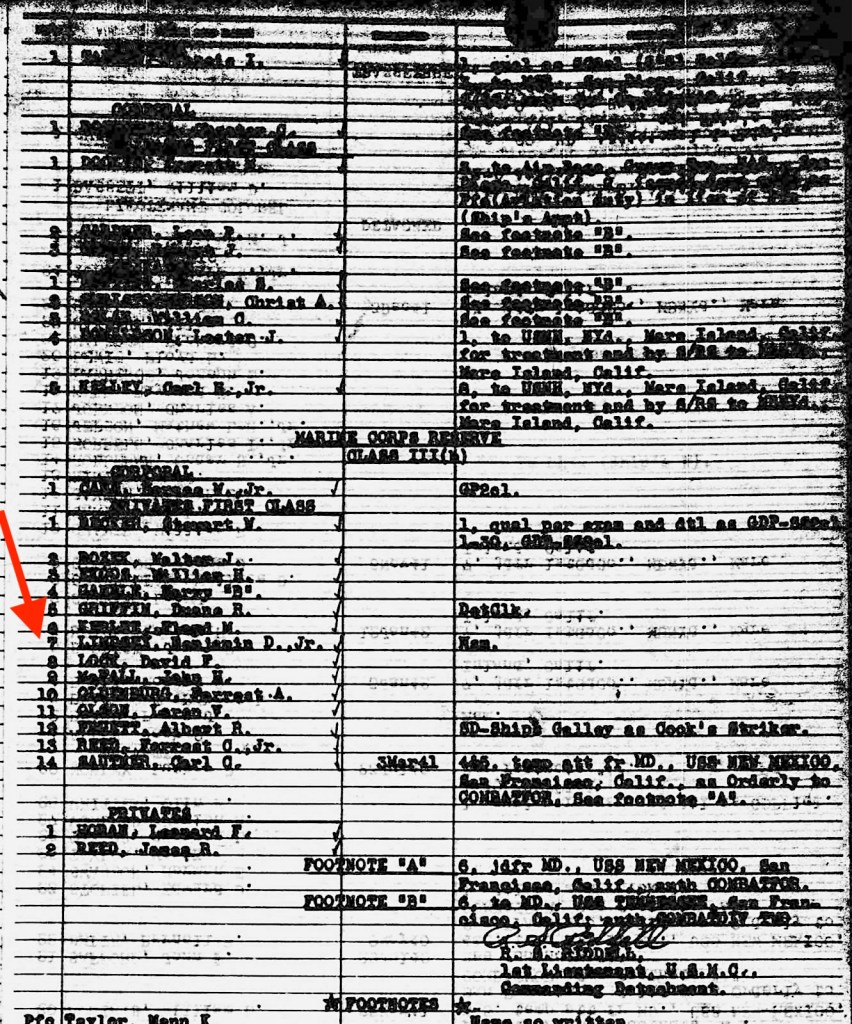

A 27 July and 31 August 1941 list of passengers aboard the USS Fanning shows Private Benjamin D. Lindsey Jr. aboard. The ship sailed from Long Beach, California. A list of Marines in the Reserves Detachment aboard the U.S.S. Pennsylvania at Pearl Harbor in October 1941 shows Benjamin D. Lindsey Jr. among the Marine privates on the ship, and muster lists of Marines in the Marines Reserve aboard the USS Pennsylvania in January and April 1942 contain the name Benjamin D. Lindsey Jr. among privates first class who were on the ship.

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, my father wrote a letter on 15 August 1942 to his brother Carlton. The letter was sent from the Pennsylvania at Pearl Harbor, c/o the Fleet Post office in San Francisco. Carlton, who had enlisted in the Army on 25 February 1942, was at Hdqrs. Det. 2nd Btn., 117th Infantry, Fort Jackson, South Carolina, and would not far down the road be sent with members of that infantry unit to England, then to France and the Low Countries, where the charge of these troops was to help liberate those countries from Nazism before marching into Germany to assist in the liberation of that country.

My father’s 15 August 1942 letter to his brother states that he was thinking of his brother (whom he addresses as “dear Bud”) because Carlton was to take exams on that day to get back into the Air Force. It also says that my father hoped to take tests to join the Naval Air Force. It further indicates that my father had had a letter from their sister Helen Blanche asking him to write her boyfriend in Alaska. This was Lee Compere, son of E.L. Compere, an adjutant general of the Arkansas National Guard whom Helen would marry in January 1944. My uncle Lee wrote detailed memoirs of his WWII experiences and gave me a copy of these memoirs.

My father’s August 1942 letter to his brother also speaks of his desire to be made corporal. At some point I believe he was made a corporal and then sergeant, and then demoted when he got into a fracas of some kind involving another officer — a fight. During his war years, he engaged in boxing contests as a “featherweight,” he sometimes told his sons.

The term “bud” or “buddy” is one that has cropped up in American culture often at wartime or when the nation is on one of its recurrent military binges, reflecting the buddy system of the military. The popular song “My Buddy,” from 1922, was revived during WWII and became a hit, being sung by Bing Crosby, Frank Sinatra, Sammy Kaye, and others.

A list of members of the Marine Detachment aboard the USS New Mexico sailing on 9 January 1943 and 21 February 1943 shows my father aboard. In April 1943, he was on a Marine muster roll for the USS West Virginia, Co. E, barracks at Pearl Harbor and also listed in the Marine detachment of the USS New Mexico, fleet post office in San Francisco.

A 20 February 1945 letter he sent his parents has no envelope or indication of from where he was writing. It notes that his unit would leave for the west coast on the following day and that he needed money. He asks his parents to send him the War Bonds he had left at home. The letter also notes that he would write his parents and send an address when he got to Camp Pendleton.

Seven days later, he sent his parents a letter from Co. B, 1st Trng. Bn., 2nd Inf. Trng. Reg., M.T.C.-S.D.A., Camp Pendleton, Oceanside, California. This says that my father had arrived at Pendleton the day before and was happy to be back in California. He had come by a monotonous five-day train ride. En route, he had gone from New Orleans to Shreveport through Coushatta, his and their birthplace, but the train was going so fast at that point, he could not recognize anyone, although he yelled from the train. He was on train 2, and notes that train 3 came through Memphis, Pine Bluff, Fordyce, and Camden, Arkansas. My father’s letter tells his mother that he would be sending a telegram the following day, and when she got it, she would see why he had done so. The letter reiterates that my father was broke, and needed the war bonds.

And that’s it — all the close documentation I have of my father’s WWII experiences before and after the bombing at Pearl Harbor, other than photos taken in Hawaii during his time there. The address from which my father sent his 27 February 1945 letter to his parents — Co. B, 1st Trng. Bn., 2nd Inf. Trng. Reg. — indicates that he served in the 1st Battalion of the 2nd Marines, which was activated in June 1942 and deployed to the Pacific theater, where, following Pearl Harbor, it participated in the bloody “island hopping” campaign, fighting at Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Saipan, Tinian, and Okinawa.

Following the war, my father came home from the war in 1945, married my mother Hattie Clotine Simpson in Little Rock in June 1948, and graduated from Hendrix College in June 1951, going from there to law school in Little Rock, and getting a law degree.

P.S. It should not ever be forgotten that not only did American men serve in World War II, but so did American women. A cousin of my father, Gloria Devore, was a Women’s Air Force Service Pilot (WASP) during WWII and served with distinction. There’s a bit of information about Gloria and her mother Olive, who was a first cousin of my grandfather Benjamin Dennis Lindsey Sr., in this previous posting.

ADDENDUM (added later):

According to my former sister-in-law, with whom I had a nice visit over Christmas 2025 at my niece’s house, my father’s brother-in-law Lee Compere told her that my father received a purple heart due to being wounded at Pearl Harbor. My uncle Lee would certainly have known that fact, so I have absolutely no reason to doubt it. As I say above, I have “always” known, of course, that he was wounded by shrapnel from an exploding bomb during the attack on Pearl Harbor. So it would make sense that he received a purple heart for this.

But somehow, the fact of the purple heart is simply not in my memory — as if I was never told of it when he and others talked about his experience at Pearl Harbor. Where the purple heart may have been as I was growing up and who ended up with it, I have no clue. I feel quite sure I never saw it.

5 thoughts on “A Series of WWII Memoirs (1): Benjamin Dennis Lindsey (1920-1969)”