As a premier researcher of Rowan County, North Carolina, Jo White Linn, states in an excellent biographical piece about Hugh Montgomery, no thorough study of Hugh’s life has ever been done, despite the fact that he rose to a position of prominence in Rowan County, amassed considerable wealth, and had children who married into highly placed families.[2] Linn’s well-documented and carefully researched study suggests that, though his life generated many records, as the lives of the rich and prominent tend to do, few of those records give us a clear picture of Hugh’s early life, which is shrouded in myth that has to be separated from fact if we’re going to see Hugh Montgomery (or, I’d add, his possible connection to other colonial Montgomery families) clearly. The two best biographical sources I’ve found for Hugh, ones that provide sound documentation rather than credulously repeating myths about him, are Jo White Linn’s article and Mary B. Kegley’s brief biography in her Early Adventurers on the Western Waters.[3]

Indicators of a Possible Kinship Connection of Hugh Montgomery to Catherine Montgomery Colhoun and James Montgomery of Augusta County, Virginia

As a descendant of Catherine Montgomery Colhoun, I’ve long been interested in this Hugh Montgomery because, as Mary B. Kegley notes, a number of indicators suggest that Hugh may have been a relative of Catherine and her likely brother James.[4] I discuss a number of those indicators in the posting I’ve just linked. They include:

• On 17 October 1765, Hugh bought from Patrick Calhoun, a son of James Calhoun, whose parents were Patrick Colhoun and Catherine Montgomery, 610 acres on Reed Creek that had belonged to James Calhoun with the deed saying that Hugh was “late of the parish and county of augusta in the Colony of Virginia.”[5]

• Hugh Montgomery had also bought 106 acres on Cripple Creek in Augusta County on 4 May 1763 from John and Mary McFarland, which they had acquired from the estate of John Noble, husband of Mary Calhoun, whose parents were Patrick Colhoun and Catherine Montgomery.[6]

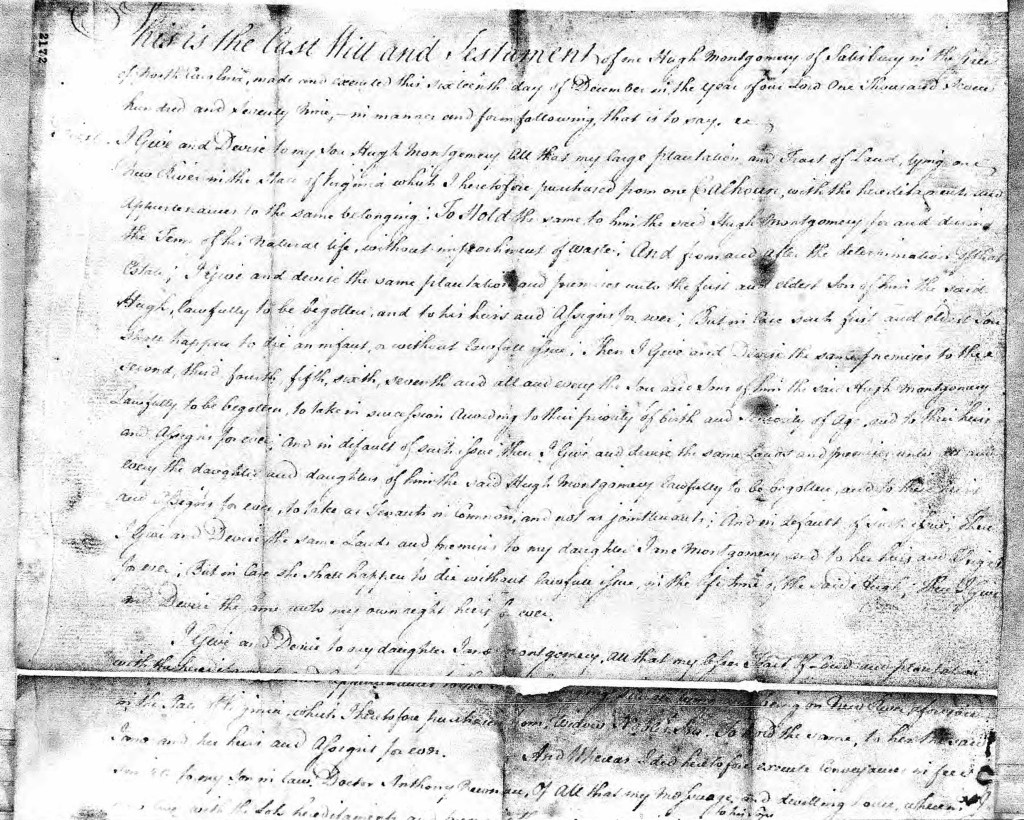

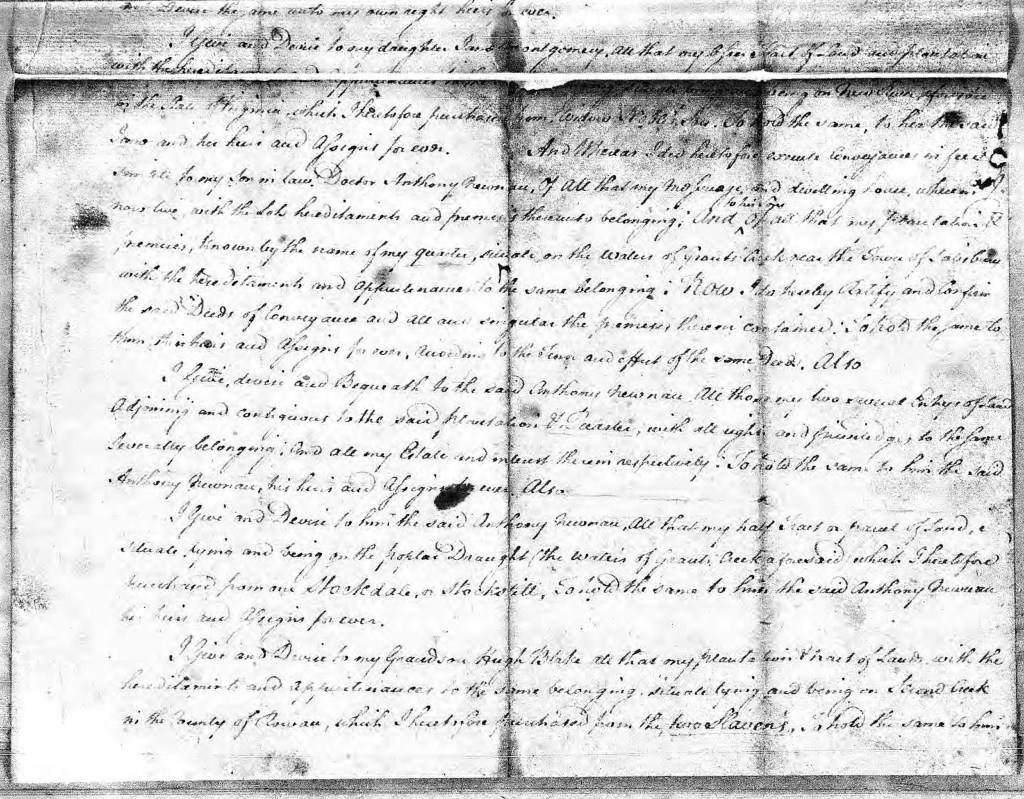

• Hugh Montgomery’s will, which he made in Rowan County, North Carolina, on 16 December 1779, also bequeathed to his daughter Jane land on the New River in Virginia, noting that he had acquired this land from “the widow Noble’s son.”[7]

• Hugh’s son Hugh Jr. lived his adult life in Wythe County, Virginia, where the land his father bought in 1765 from James Calhoun’s son Patrick was located after that county was formed from Augusta County (by way of Montgomery, Fincastle, and Botetourt Counties) in 1790.[8] Hugh willed the plantation he acquired from Patrick Calhoun to his son Hugh. This land was close to the land on Reed Creek that John Ewing Colhoun, son of James’ brother Ezekiel, sold to Robert Montgomery, son of James Montgomery, on 5 September 1771.[9] Hugh Montgomery Jr. was in Wythe County by 28 December 1790, when he was made administrator of the estate of Mary Ewing.[10] On 17 August 1792 John Brown, executor of his father’s estate, conveyed property to Hugh Jr. in Wythe County, with the record noting that Hugh Jr. was then living in Wythe County. Note, by the way, the surname Ewing here: as I’ve discussed previously, a Ewing family found in records of Augusta County, Virginia, appears to have been closely related to the family of Ezekiel Calhoun’s wife Jean/Jane Ewing.

These records suggest to me that there was likely a close connection between Hugh Montgomery, Catherine Montgomery Colhoun, and James Montgomery. Mary Kegley thinks that the three may have been siblings, though, as she states, the relationship has not been confirmed.[11] Noting that Hugh appears to have been some years younger than Catherine and James, other researchers have suggested that Hugh was a son of James. I have also not seen proof of that connection. Mary Kegley thinks that Hugh did not live in Augusta (later Wythe) County at any point, though, as noted above, when he bought James Calhoun’s Reed Creek tract there on 17 October 1765, the deed says that Hugh was “late of the parish and county of augusta in the Colony of Virginia.”

Daniel Campbell Montgomery proposes, citing no evidence, that Hugh was a son of James Montgomery of Augusta County, Virginia, and states,[12]

As early as 1752 Hugh is on record as owning slaves and land on a branch of Reed Creek [in Augusta County, Virginia].

It’s not clear to me what record Daniel C. Montgomery may have been citing here. His statement lacks any citation of a source. Though it appears that lists of tithables, delinquents, and petitioners in Augusta County are extant for that year, the earliest tax lists available for the county at the FamilySearch site date from 1777.

The Difficulty of Documenting Hugh’s Place and Date of Birth

I’ve stated that it appears Hugh Montgomery was some years younger than Catherine Montgomery Colhoun and James Montgomery. As Jo White Linn notes, the Daughters of the American Revolution previously accepted lineages for Hugh based on claims that he gave Revolutionary service in Pennsylvania as a captain of the 4th Continental Artillery and also as a colonel in the North Carolina Marines.[13] These lineages state that he was born in December 1720 in County Derry/Londonderry, Ireland, and had a wife named “Lady Catherine” Moore.[14]

“What are the facts?” Linn asks. Her article about Hugh is an attempt to answer that all-important question.

As Linn notes, “[Hugh’s] Revolutionary War military service in Pennsylvania in 1777 is a fiction.”[15] Records consistently place Hugh Montgomery in Rowan and Wilkes Counties, North Carolina, from 1756, when he came to Salisbury, up to the end of his life in 1779. And far from being a Revolutionary hero, he and his son-in-law John Blake and several other men were called before Rowan County court on 8 August 1777 to answer charges of disloyalty to the Revolutionary government of North Carolina.[16] Hugh did give Revolutionary service (Linn calls this “checkered service”) on the Rowan Committee of Safety, served in the North Carolina Provincial Congress, and received payment for goods given to Revolutionary troops, but no records anywhere show him serving as an artillery captain or Marine colonel.[17] As Linn concludes, [18]

Hugh Montgomery could not possibly have been a military hero on two fronts simultaneously during the Revolutionary War, and his patriotic service appears to have been grudging.

Apparently due to its recognition that documentation supplied for lineages for Hugh Montgomery that it had accepted in the past is flawed or lacking, DAR now maintains a correction file for Hugh.[19]

If information provided about Hugh’s Revolutionary service record by DAR members who entered that society in the past as his descendants was less than reliable, then the question arises whether the December 1720 birthdate for Hugh that appears in many of these DAR applications is also questionable. For a long time now, I’ve sought documentation of this birthdate, and of the County Derry, Ireland, place of birth attributed to Hugh by many researchers, without having found such documentation.

The Wikipedia article for this Hugh Montgomery, which calls him “Hugh Montgomery (soldier),” also states that he was born in 1720 in Ireland, and names James Montgomery (abt. 1690-1756) and wife Anne Thompson as Hugh’s parents – that is, the James Montgomery of Augusta County, Virginia, who was a brother of Catherine Montgomery Colhoun.[20] The Wikipedia article, which also states erroneously that Hugh commanded a Rowan County regiment during the Revolution, offers no documentation for its date and place of birth or the names of Hugh’s parents. Wikipedia’s biography also states, erroneously in my view, that Hugh Montgomery was a “near relative of British General Richard Montgomery, who fell at the Battle of Quebec, in 1775.” The footnote for this claim has nothing to do with what it purports to be documenting. The quotation featured here is actually from John H. Wheeler’s Reminiscences and Memoirs of North Carolina and Eminent North Carolinians; this (dubious) kinship claim is not documented by Wheeler.[21]

I am belaboring this point – that documenting the date and place of birth of Hugh Montomgery is not a simple task and is impeded by myths that shroud the few facts available to us – not because I want to bash historians and researchers of the past, but because I want my own research into my ancestral families’ origins to be fact-based and not myth-based.

I have been told that the 1720 year of birth is inscribed on Hugh’s tombstone in the Old English cemetery at Salisbury, but the researcher who has told me this did not confirm the source of that information when I asked if a transcription has been done or if someone has actually seen the tombstone or a clear photo of it and verified that the information is correct. The photo of the tombstone at Hugh’s Find a Grave memorial page does not show the tombstone clearly enough for any inscription to be made out (see the photo at the head of the posting).[22] The tombstone appears, in fact, to be badly eroded.[23] This Find a Grave memorial page states that Hugh was born in December 1720. It’s not clear if this information is being transcribed from his tombstone. If so, the memorial page does not state this. The only transcription of this tombstone that I’ve found is Frederick M. Yancey’s 1940 transcription for Historical Records Survey of North Carolina, which indicates that the tombstone gives a death date of 18 December 1776 [sic] and apparently no other information except for Hugh Montgomery’s name.

The Mamie McCubbins collection housed at the Edith Clark history room of Rowan County public library in Salisbury has a collection of extensive documents relating to Hugh Montgomery gathered by Mamie (Mary Louisa) Gaskill McCubbins during her many years of genealogical research. These include a typescript entitled “Hugh Montgomery” whose author is not named. This document states that Hugh Montgomery was born in Ireland in 1720. No source is cited for this birthdate. The typescript reproduces biographical material about Hugh from William Alexander and W. Thomas Smith’s Family Tree Book and from Wheeler’s Reminiscences and Memoirs of North Carolina and Eminent North Carolinians.[24] But neither of those sources states a birthdate for Hugh Montgomery.

I don’t doubt that Hugh Montgomery was born in Ireland, and the sparse documentation we have about his earlier years – as we’ll see in a moment, he arrived in Salisbury in 1756 with a deed stating that he was previously in Philadelphia and was a merchant – makes a 1720 birthdate plausible to me. I’m merely noting the lack of solid documentation for Hugh’s Irish birthplace and his year of birth. These may be traditions handed down among his descendants, and if so, it seems to me they should be cited as such and if possible, should be tracked to their earliest roots. Kegley says, “Family records state that [Hugh Montgomery] is the son of a Hugh Montgomery of Scotland,” and in documenting this statement, she cites “family information.”[25]

John H. Wheeler’s Account (1884) of the Life of Hugh Montgomery

I’ve previously cited John H. Wheeler’s 1884 biographical sketch of Hugh Montgomery, which appears to depend heavily on family traditions. It might be worthwhile for me to provide that sketch here in full. Here’s what Wheeler says about Hugh before he discusses Hugh’s children:[26]

Prominent among the names of this committee [i.e., the Rowan Committee of Safety] is the name of Hugh Montgomery; he was a native of Ireland. At an early age he fell in love with a Miss Moore, who was of noble birth. This was strongly opposed by her friends, but the attachment was reciprocated – and she was conveyed secretly on board of a ship, where she met her lover and was married; the youthful pair escaped in safety to America. He was himself of a goodly stock, a near relative of General Richard Montgomery, who fell in the battle of Quebec, (Dec. 1775). He settled first in Pennsylvania and afterward removed to Salisbury, North Carolina. He was constant and active in promoting the cause of independence and was one of the most fixed and forward of the daring spirits of that day. Among whom were Griffith Rutherford, John Brevard, Matthew Locke, John Louis Beard, William Sharp, Maxwell Chambers, Wm. Kennon, Geo. Henry Barringer, John Nesbit and Charles McDowell.

By his enterprise and industry he amassed a handsome fortune. He died at Salisbury Dec. 23d, 1779, leaving one son and seven daughters.

The Story of Miss Moore or “Lady Mary Moore” or “Lady Catherine Sloan Moore

As Jo White Linn states from the outset of her article about Hugh Montgomery, documenting the family story of Miss Moore of noble birth was her key objective as she began to research Hugh’s life and dig for facts underneath layers of myth. Linn opens her article stating,[27]

Descendants of Hugh Montgomery requested authentication of the noble lineage of the wife of Revolutionary War officer Hugh Montgomery, the Lady Catherine Sloan Moore. For two hundred years the Lady’s descendants had passed along the story that she had forsaken a life of rank and privilege to elope to America with her forbidden sweetheart. The family wanted to know if the lovely tale could be verified. Family tradition held that when Montgomery was planning to come to America, he was denied her hand because she was of the nobility. With breaking heart, he had boarded ship; at the last moment friends smuggled the Lady aboard, and they were married by the ship’s captain en route to America. While there are several versions of the story, repeated at a succession of Granny’s [sic] knees, the romantic tradition concerning Lady Catherine Sloan Moore did not vary.

The fact-based story that Jo White Linn uncovered as she dug for documentation to substantiate these family stories about Hugh’s early life is fascinating. Hugh Montgomery arrived in Rowan County by 20 July 1756, when Morgan Bryan Jr. sold him 150 acres on the north bank of the Yadkin River above the mouth of the Elk River, with the deed stating that Hugh was “late of Pennsylvania.”[28] On 12 August 1756, William Montgomery and his wife Fortune then sold Hugh a lot on the west square of Salisbury, with the deed stating that William was an ordinary keeper in Salisbury and Hugh was “late of Philadelphia” and was a merchant.[29]

I’d be inclined to think there might have been some kinship connection between Hugh and William Montgomery, except that I’m told that DNA findings apparently indicate that descendants of William – we assume that their lineages are solid and have been verified by genealogical evidence – belong to a Y-DNA haplogroup different from that to which descendants of the James Montgomery thought to be Hugh’s relative belong. To the best of my knowledge, proven male descendants of Hugh have not been tested.

Much confusion about William Montgomery and his wife Fortune has been generated by researchers claiming that Fortune was “Mary Fortune” – i.e., Fortune was the surname of William’s wife rather than her given name – when this and other documents make clear that Fortune was the given name of William’s wife. The William Montgomery with wife Fortune who sold property to Hugh Montgomery in Salisbury, North Carolina, in August 1756 is very likely the William Montgomery who, along with John Montgomery, bought 150 acres, Jones’ Gift, in Baltimore County, Maryland, from Nathaniel Porter on 25 January 1744, and who then sold David Maxfield this and other pieces of land on 19 June 1747 along with John Montgomery and William’s wife Fortune, with the deed stating that the Montgomerys lived in New London township, Chester County, Pennsylvania.[30] In a posting to the Montgomery Genealogy group on Facebook on 14 August 2018, Michael Shulman suggests that Fortune was Fortunata Dawson, daughter of Thomas Dawson and Mary Cowan of Chester County, Pennsylvania. Shulman notes that Fortunata had a brother Abraham Dawson whose 1760 will in Chester County names a cousin Mary Montgomery.

Hugh’s Two “Wives,” Catherine Sloan and Mary Montgomery

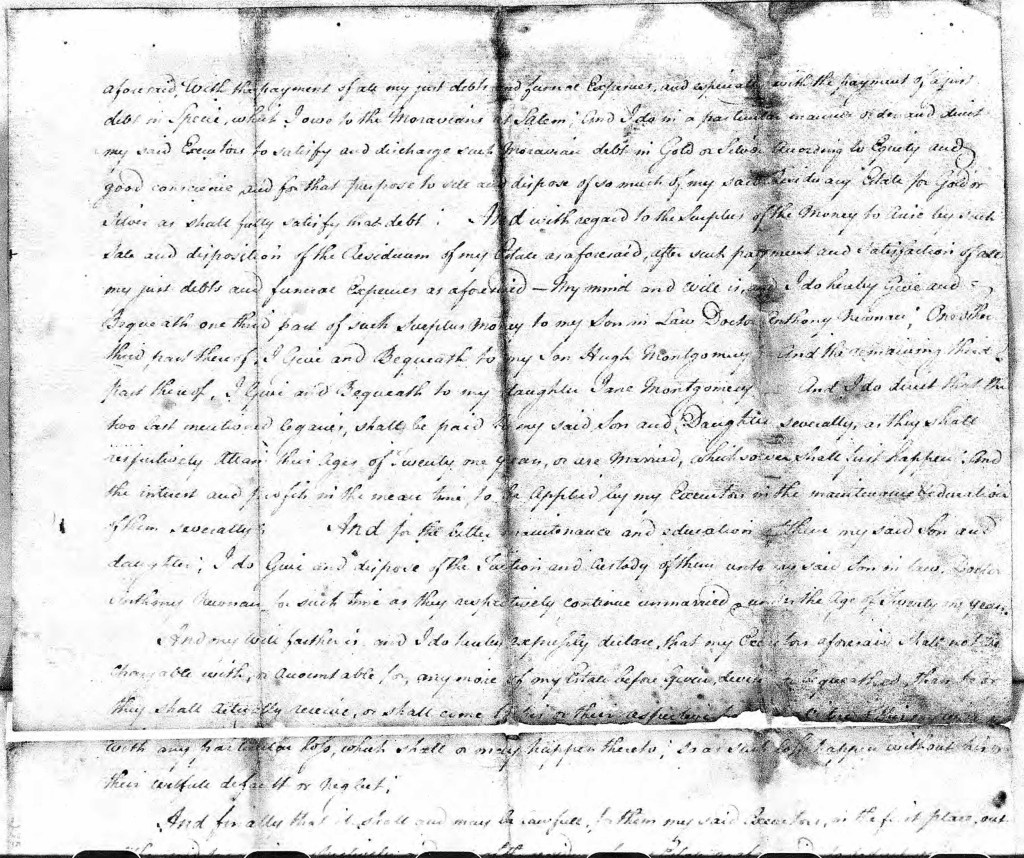

And now to return to the fascinating fact-based story Jo White Linn uncovered as she dug for information to verify the long-told story that Hugh left Ireland in company of a Lady Mary or Catherine Moore whose family would not permit their marriage, then married Miss Moore aboard ship and brought her to America: as I noted above, Hugh Montgomery made his will in Salisbury on 16 December 1779 and died there on 23 December 1779.[31] The will names no wife.

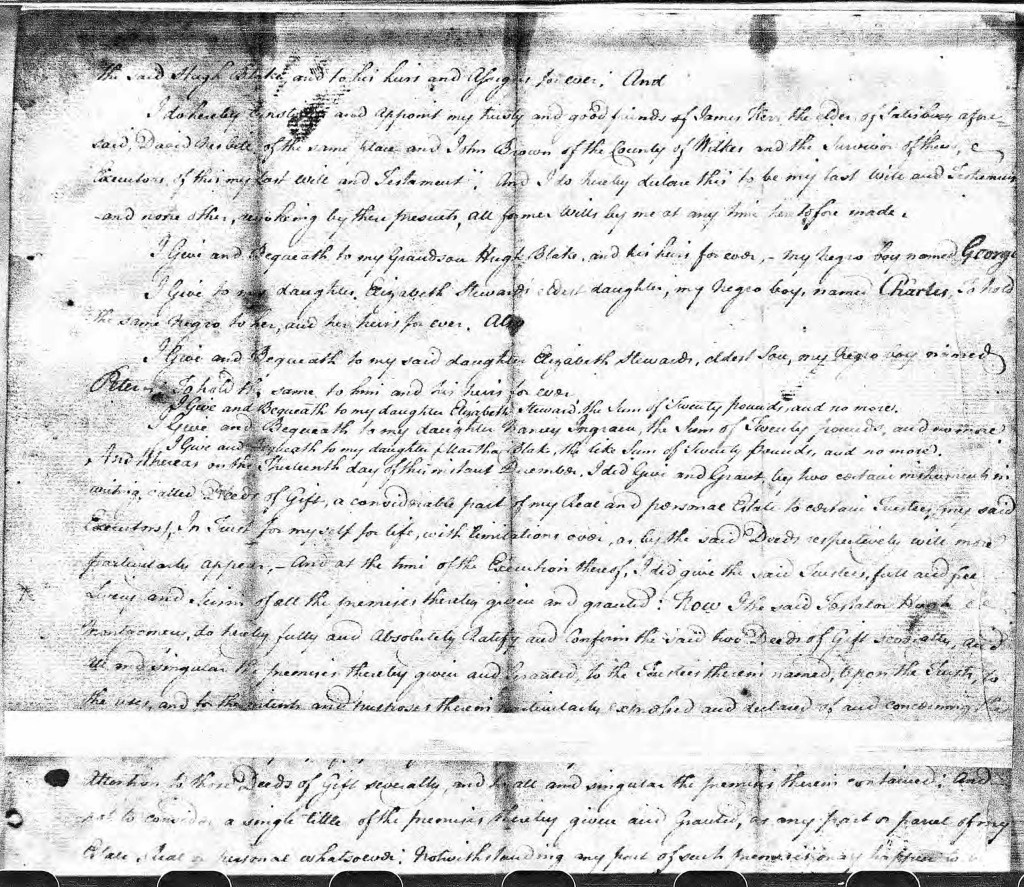

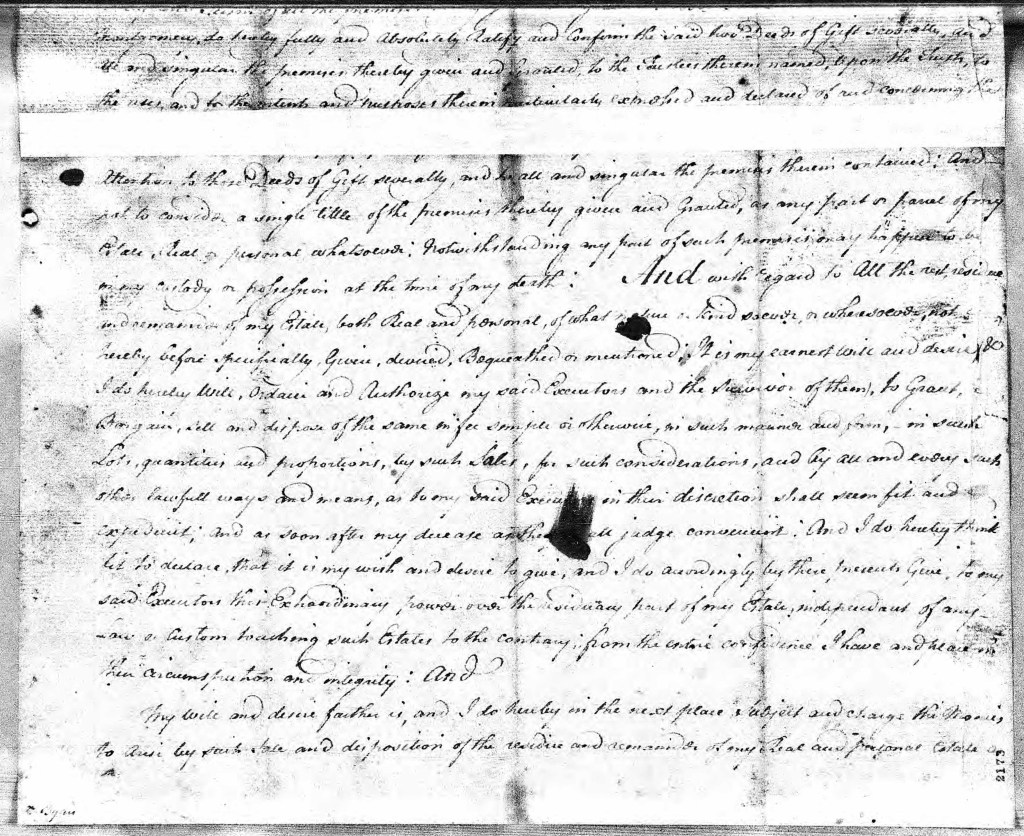

It states, however, that on 13 December, Hugh had made two deeds of gift to place in the hands of trustees “a considerable part” of his real and personal estate, deeds of gift that he ratified and confirmed with the will. These deeds are filed in Wilkes County, North Carolina. They show that on 13 December 1779, three days before he made his will, Hugh placed in the hands of James Kerr and David Nesbitt of Salisbury and John Brown of Wilkes County valuable property “for the natural love & affection which Montgomery has for his two daughters and children Rebecca and Rachel by his present wife Catharine, heretofore Catharine Sloan, and to make provision for their education and maintenance and future support and advancement in the World….”[32]

The information in this deed of gift that Hugh Montgomery had a wife Catherine (surname Sloan) and two daughters by her comes as a great surprise when we note that on 11 February 1780, when Hugh’s will was proved at Rowan County court, his wife Mary Montgomery came into court and claimed her dower share of his estate.[33] Rowan County deeds show Hugh with wife a wife named Mary by 23-4 April 1762, when he and wife Mary sold property in Rowan County to William McConnell, with Mary signing along with Hugh and the deed stating that she was Hugh’s wife (Rowan County, North Carolina, Deed Bk. 4, pp. 709-712). This is the same Mary Montgomery who was enjoined by the county court on 8 May 1777 to keep the peace towards Hugh Montgomery, giving bond with her sons-in-law Anthony Newnan and John Blake to satisfy the court.[34] At the same time that Hugh Montgomery was maintaining Catherine Sloan and two daughters by her in Wilkes County, he had a wife Mary in Salisbury and a family by Mary. Jo White Linn concludes:

Hugh Montgomery knew he wasn’t married to Catherine Sloan; his trustees and executors knew it; and his wife Mary and his children by her knew it.

This was almost certainly the bone of contention between Hugh and Mary that led to her being charged in May 1777 by Rowan County court to keep peace with Hugh. And it was why Hugh secured the futures of Catherine and her daughters Rebecca and Rachel three days prior to making his will, assuring their legal claim to a handsome portion of his property when he died.

In Jo White Linn’s view, Catherine Sloan is likely the “Lady Mary Moore” or “Lady Catherine Sloan Moore” of family lore, and “the records are none too kind to the romantic fiction” surrounding her story.[35] Hugh could not have been married to Catherine if he was legally married to Mary, and Mary would not have been given a dower share of his estate unless the two were, in fact, legally married.

Linn concludes,

The saga of Hugh Montgomery has provided a fascinating study, the family tradition pitted against the varied primary source material interpreted by the laws of the time.

If there’s any grain of truth to the longstanding family story that Hugh Montgomery came from Ireland to Pennsylvania in the company of an Irish noblewoman with whom he had fallen in love and whom he married aboard ship to America, then I think one has to conclude that Catherine Sloan is likely the person spoken of in this romantic story – but it appears that, though Hugh may well have had children by Catherine, he did not actually marry her. Though Jo White Linn is inclined to think that Catherine is the “lady” spoken of in the stories handed down in this family, she also says that it would be an ironic twist if Hugh’s legal wife Mary turned out to be that lady. And she ends her study by saying that further research in Pennsylvania records seems imperative if we’re ever to get to the bottom of this story.

Some Final Notes on the Importance of Sound Genealogical Research Used in Tandem with DNA Findings

When it comes to ascertaining if Hugh Montgomery is closely related to Catherine Montgomery Colhoun and her likely brother James Montgomery, DNA research may prove conclusive. As I noted previously, to my knowledge, Montgomery surname Y-DNA studies to this point do not include a test by a proven male descendant of Hugh Montgomery. It also seems (to me, at least) important to note that, though some genealogical researchers nowadays seem to use DNA findings in an almost absolutist way to sort family lines, DNA-based information is only as good as the genealogical research it employs to discuss those family lines – if, that is, DNA findings are being used judiciously.

If DNA findings are to yield the significant information they promise to yield when used in tandem with sound genealogical research, it seems to me that those of us using DNA evidence need to pay attention to what constitutes good genealogical research. At its best, good genealogical research demands collaboration between those engaged in traditional genealogical research and those emplying the new tool of DNA analysis. As an academic, I was trained to view scholarly research of any sort as a collaborative enterprise that demands mutual trust, respect, and sharing on the part of a discourse community all of whose members are seeking to arrive collectively at the truth. I was also taught that advancing hypotheses, then allowing members of the community to critique them and, often, to find them wrong, is an essential part of the research process.

These core principles of good research in any academic field seem to me especially significant when families have for a long time circulated confusing misinformation that derails sound documentation – misinformation like several pieces of information I’ve just discussed that have long been handed down regarding Hugh Montgomery, or, in the case of my own Montgomery ancestor Catherine Montgomery Colhoun, the claim that her grandson John C. Calhoun states in some letter somewhere that he had a (great-) grandfather named Hugh Montgomery, and that this Hugh came with his daughter Catherine to South Carolina and died there.

No such letter of John C. Calhoun exists. And there is absolutely no documented evidence that I’ve seen anywhere that Catherine Montgomery Colhoun had a father named Hugh Montgomery or that this purported father came to South Carolina with her and died there.

It’s hard to give up myths, I know. People schooled on them often bridle when cherished myths are questioned. But asking questions about them and seeking sound documentary evidence are essential steps in moving lineages back in time – especially when we want those lineages to be solid and useful for those employing the new tool of DNA analysis to further our understanding of the history and connections of family lines.

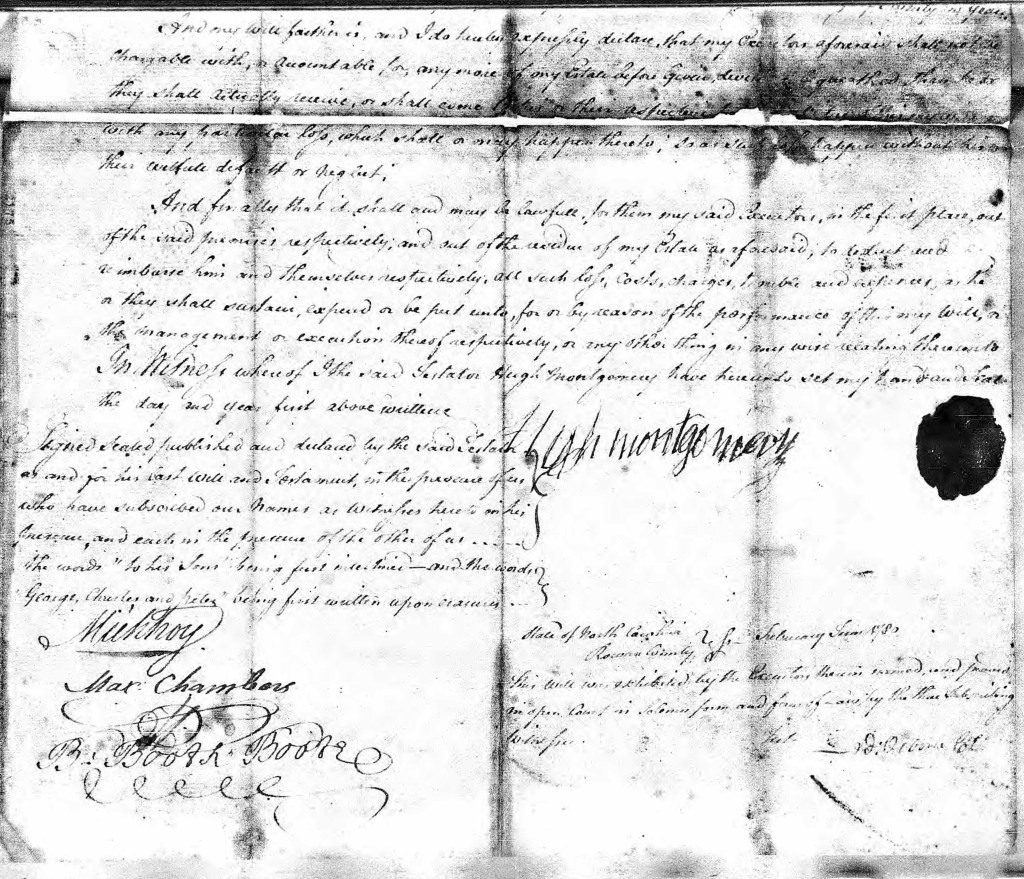

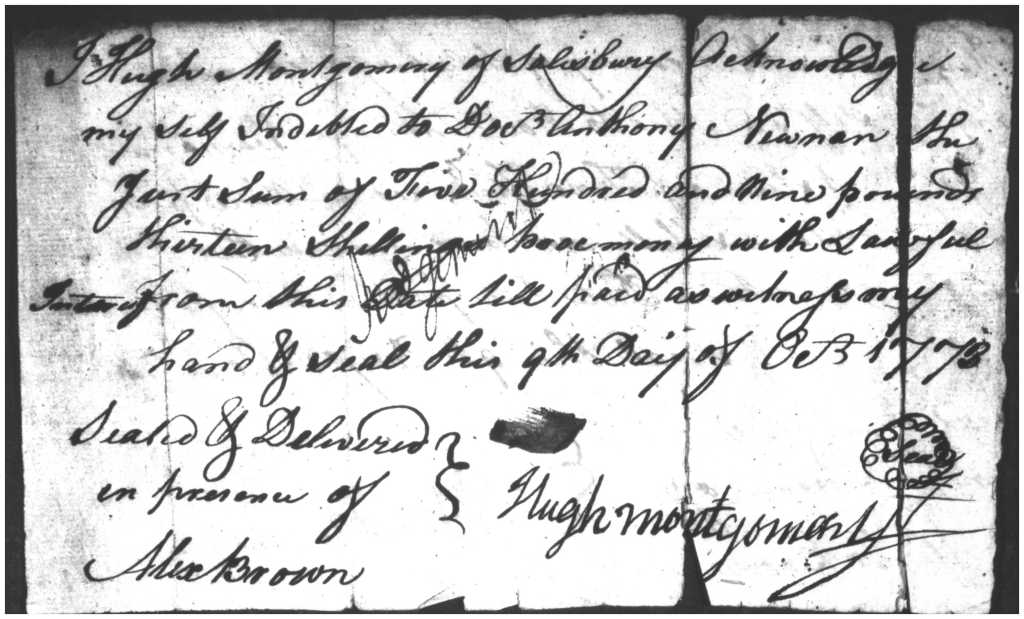

Here’s (above) Hugh Montgomery’s original will as held by the North Carolina Archives in Raleigh in its files of original wills from North Carolina counties. It’s clear to me that, though Hugh signed the will, he did not write it, and that he was likely very sick at the time he made his will. Compare his signature on the will with his signature to this 9 October 1773 note found in his loose-papers estate file held by North Carolina Archives:

[1] The date and place of death are stated in John H. Wheeler, Reminiscences and Memoirs of North Carolina and Eminent North Carolinians (Columbus, Ohio: Columbus Printing Works, 1884), p. 396. Hugh Montgomery made his will in Salisbury on 16 December 1779, and it was probated at court in February 1780 (Rowan County, North Carolina, Will Bk. E, pp. 41-47). In the diary kept by the Moravian community at Salem (the so-called Salem Diary), the entry for 30 December 1779 states, “We hear that the Mr. Montgomery who bought the land at the Mulberry Fields was buried in Salisbury on Dec. 27th”: see Adelaide L. Fries, ed., Records of the Moravians in North Carolina, vol. 3: 1776-1779 (Raleigh: Edwards & Broughton, 1926), p. 1321.

[2] Jo White Linn, “Hugh Montgomery of Rowan County: One Man with a Fast Horse,” Rowan County Register 7,3 (August 1992), pp. 1591-1606.

[3] Mary B. Kegley, Early Adventurers on the Western Waters, vol. 3, pt. 2: The New River of Virginia in Pioneer Days 1745-1805 (Marceline, Missouri: Walsworth, 1995), pp. 726-8.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Augusta County, Virginia, Deed Bk. 14, pp. 2-6.

[6] Ibid., Bk. 11, pp. 328-9; and Augusta County, Virginia, Will Bk. 1, p. 480.

[7] Rowan County, North Carolina, Will Bk. E, pp. 41-7.

[8] Augusta was broken into a consecutive series of counties in the section of the county that eventually turned into Wythe County.

[9] Botetourt County, Virginia, Deed Bk. 1, pp. 302-4.

[10] Wythe County, Virginia, Court Order Bk. 1790-1, p. 40.

[11] Kegley, Early Adventurers on the Western Waters, vol. 3, pt. 2, p. 726.

[12] Daniel Campbell Montgomery, The Descendants of Hugh Montgomery Sr. and Some Related Families (priv. publ., Greenville, Mississippi, 1976), p. 9.

[13] Linn, “Hugh Montgomery of Rowan County: One Man with a Fast Horse,” pp. 1591-2.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid., p. 1592.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid., p. 1603.

[19] “Montgomery, Hugh,” Ancestor no. A078975, National Society of Daughters of the Revolution website.

[20] “Hugh Montgomery (soldier),” Wikipedia.

[21] Wheeler, Reminiscences and Memoirs of North Carolina and Eminent North Carolinians, p. 396.

[22] See Find a Grave memorial page of Hugh Montgomery, the Old English cemetery, Salisbury, Rowan County, North Carolina, created by Patsy Hunt, with a tombstone photo by NCGenSeeker.

[23] In his Carolina Cradle: Settlement of the Northwest Carolina Frontier, 1747-1762 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1964), Robert W. Ramsey says (p. 166) that Hugh Montgomery’s tombstone “may yet be seen in the ‘English cemetery’ in Salisbury.” Ramsey offers no information about what the tombstone states, and he erroneously has Hugh dying in 1780.

[24] William Alexander and W. Thomas Smith, Family Tree Book: Listing the Relatives of General William Alexander Smith and of W. Thomas Smith (priv. publ., Los Angeles, 1922), pp.105-9; and Wheeler, Reminiscences and Memoirs of North Carolina and Eminent North Carolinians, p. 396.

[25] Kegley, Early Adventurers on the Western Waters, vol. 3, pt. 2, pp. 726-7.

[26] Wheeler, Reminiscences and Memoirs of North Carolina and Eminent North Carolinians, p. 396.

[27] Linn, “Hugh Montgomery of Rowan County: One Man with a Fast Horse,” p. 1591.

[28] Rowan County, North Carolina, Deed Bk. 3, pp. 321-2.

[29] Ibid., Bk. 2, pp. 385-6. See Ramsey, Carolina Cradle, p. 166 for a discussion of this deed.

[30] Baltimore County, Maryland, Deed Bk. Liber TB, no. C, f. 572, and Liber TB, no. D, f. 14, as abstracted in Robert W. Barnes, Baltimore County Families, 1659-1759 (Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, 1996), pp. 453, 512.

[31] See supra, n. 1.

[32] Wilkes County, North Carolina, Deed Bk. A-1, pp. 157-169. See Linn, “Hugh Montgomery of Rowan County: One Man with a Fast Horse,” pp. 1596-7.

[33] Rowan County, North Carolina, Court Order Bk. 4, p, 326; see Linn, “Hugh Montgomery of Rowan County: One Man with a Fast Horse,” p. 1595.

[34] Rowan County, North Carolina, Court Order Bk. 4, p. 105; see Linn, “Hugh Montgomery of Rowan County: One Man with a Fast Horse,” p. 1594.

[35] Linn, “Hugh Montgomery of Rowan County: One Man with a Fast Horse,” p. 1597.

2 thoughts on “Hugh Montgomery (abt. 1720? – 1779) of Philadelphia and Rowan and Wilkes County, North Carolina: Some Notes”