The Longstanding (and Erroneous) Tradition of the Name James

Brian Anton writes,

The apparently erroneous idea that the grandfather’s name was “James” emerged in the 1880s based on two sources, both of uncertain origin.

The first of these two sources was a biographical sketch of John C. Calhoun, a grandson of the immigrant, written by William Pinkney Starke in the 1880s and published (in slightly truncated form) in 1900 in J. Franklin Jameson’s book Correspondence of John C. Calhoun.[2] As Brian Anton explains, John C. Calhoun’s son-in-law Thomas Green Clemson invited Colonel Starke to the Calhoun family home at Fort Hill, South Carolina, in 1883 to do research for a biography of John C. Calhoun. At Fort Hill, Starke had access to John C. Calhoun’s papers and other “materials of neighborhood tradition” about the Calhoun family. No papers of John C. Calhoun that have surfaced to date ever show him naming his immigrant grandfather. As I’ll explain in a moment and as Brian Anton notes, John C. Calhoun states in several letters – without naming his grandfather – that he, his wife, and children came to America in 1733 from County Donegal, Ireland.

Apparently on the basis of “neighborhood tradition,” W. Pinkney Starke chose to give the immigrant Calhoun ancestor the name James. Starke wrote,[3]

Among the emigrants from Scotland to North Ireland who crossed the channel early in the eighteenth century was a family of Colquhouns and another of Caldwells. The Gaelic clan Colquhoun is said to have been very respectable in numbers. The Caldwells were Lowlanders from the Frith of Solway. The Calhouns, as we shall henceforth call them, settled near Donegal in the northwestern part of the island, in which country Patrick Calhoun, the father of John Caldwell Calhoun, was born in 1723. In the years 1727-28-29 the north of Ireland suffered from drought. Owing to a succession of bad crops a number of the discontented and impoverished Scotch settlers concluded to leave Ireland, nor were they altogether satisfied with the religious situation. Four thousand emigrants to America left Ireland in one season. In the year 1733 a family of Calhouns emigrated to America. One of the three brothers was James Calhoun, who with Catherine, his wife, and four sons, James, William, Patrick, and Ezekiel, had resided in Donegal. They landed in New York, but soon removed to the western part of Pennsylvania, where they settled not far from the Potomac River.

Brian Anton notes that as early as April 1901, when the South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine announced in its “Publications Received” section the arrival of J. Franklin Jameson’s Correspondence of John C. Calhoun, with its “Account of Calhoun’s Early Life” by W. Pinkney Starke, the editor stated that “like all family histories founded upon family traditions instead of original research, [Starke’s ‘Account’] is full of errors.”[4] I think it’s likely that the editor making this statement was A.S. Salley Jr., who published a series of well-researched articles about the Calhoun family of South Carolina in the South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine in 1906.[5] Salley was editor of this journal in 1901.

And – again, I’m citing Brian Anton’s outstanding essay here[6] – when he published his biography of John C. Calhoun in 1917, William Montgomery Meigs stated,[7]

There is no doubt at all as to the presence in America of this one member of the generation [i.e., the immigrant Calhoun ancestor with wife Catherine] preceding that of the four brothers, but I know of no evidence tending to bear out Col. Starke’s statement that her husband’s name was James and that James emigrated, accompanied by two brothers, as well as by his own immediate family.

So much for W. Pinkney Starke’s account of the immigrant ancestor of the Calhoun family of the Long Cane settlement in South Carolina, which erroneously identified that ancestor as James Calhoun. The second of the two sources to which Brian Anton refers when he speaks of the mistaken belief that John C. Calhoun’s grandfather was named James Calhoun is a mysterious (and, in my judgment, nonexistent) source identified in several places as The Memoirs of John Ewing Colhoun. As Brian Anton explains, when he applied for membership in the Sons of the American Revolution in 1890 or thereabouts, John C. Calhoun’s grandson of the same name cited The Memoirs of John Ewing Colhoun as one of his source documents.[8]

And in her Notable Southern Families, published in 1918, Zella Armstrong also cited this source, writing,[9]

In 1733 James Calhoun emigrated from the County of Donegal, Ireland, with his wife Catherine Montgomery. They brought over with them four sons, and one daughter, James, Ezekial [sic], William and Patrick and Catherine. Catherine was married to a Mr. Noble…. The father of James, the emigrant, was Patrick Calhoun, whose father was James, and so on alternating with these two names for several generations.

As Brian Anton notes, the daughter of the immigrant Calhoun ancestor who married John Noble was named Mary and not Catherine. And no document entitled Memoirs of John Ewing Colhoun has ever been found. In my view, it’s not likely to be found, since it doesn’t exist.

The Estate Papers of Patrick Colhoun the Immigrant Ancestor

Due to these multiple streams of misinformation, it was long thought that the immigrant ancestor of the Calhoun family to which John C. Calhoun belonged was one James Calhoun with wife Catherine, who came from County Donegal, Ireland, to Pennsylvania in 1733. Then the following happened: this is A.S. Salley writing in 1938 in a statement entitled “The Grandfather of John C. Calhoun”:[10]

Although several earlier writers had stated that the husband of Mrs. Calhoun and the father of her five children was named James; that the family had first settled in Pennsylvania; had later removed to Virginia and then to South Carolina, this writer was not able to find any record of the name of the husband and father, or any record of the family having lived in Pennsylvania before settling in Virginia, so he avoided any reference to the uncertain claims theretofore presented and unsupported by any references to records. Time has vindicated the writer’s judgment in ignoring those unsupported claims. During the latter part of 1936, Mr. George T. Edson, of Beatrice, Nebraska, editor of The Stewart Clan Magazine, discovered in the probate court records of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, records of administration on the estate of one Patrick Calhoun which show that he was the husband of Mrs. Catherine and the father of her four sons who figured in Augusta County, Virginia, from 1746 to 1756.

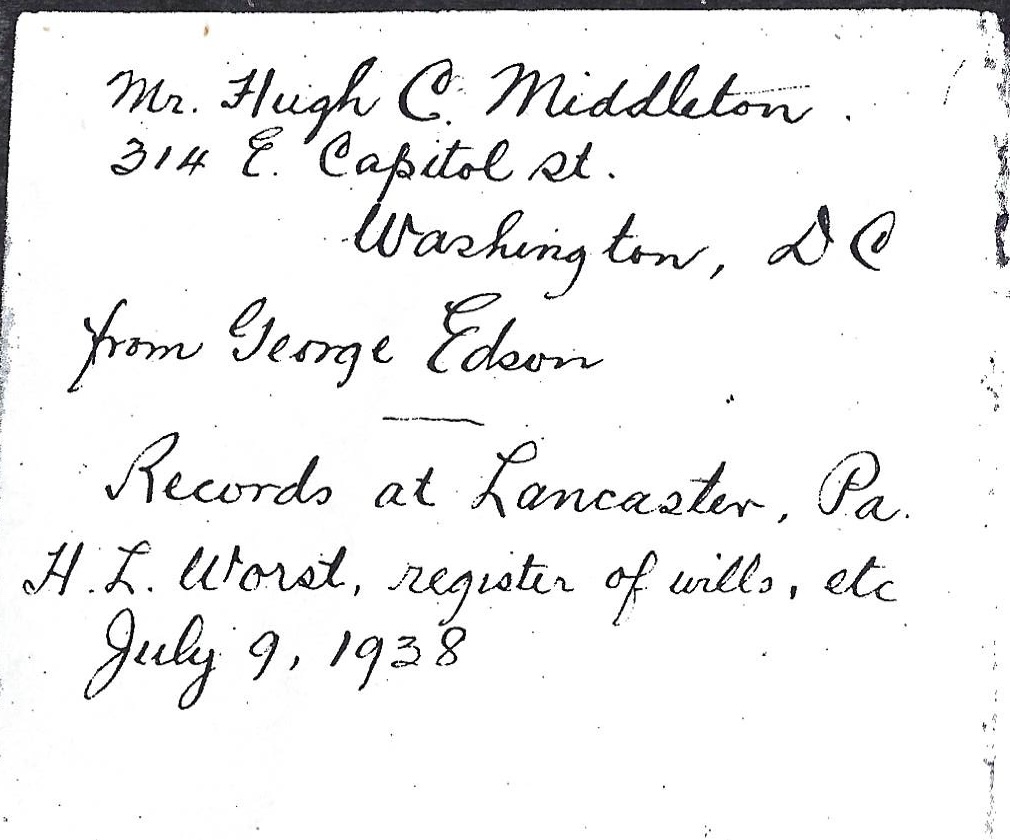

I’ve discussed the Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, estate documents of the immigrant Patrick Colhoun in previous postings (here and here), providing digital images of them which I’m including again in this posting. As the postings I’ve just linked note, photocopies of the estate documents of Patrick Colhoun that George T. Edson found in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in 1936 are in the John C. Calhoun collection of the South Caroliniana Library at University of South Carolina in Columbia. My copies are from that source. They’re marked with a handwritten statement that they’re from George Edson, and also have the name Hugh C. Middleton written on them – all these notes are in the same hand – with a notation that Hugh Middleton’s address was 314 E. Capitol St., Washington, D.C. I take these notes to mean that George Edson sent copies of Patrick Colhoun’s estate documents to Hugh Middleton, and that the South Caroliniana Library then received the copies from Hugh Middleton. In the same handwriting is another note that the original records are in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, and were in the keeping of that county’s register of wills H.L. Worst when George Edson found the records in 1936.[11] The written statement on the copies held by South Caroliniana Library has the date 9 July 1938, which may be the date on which H.L. Worst officially verified these papers as copies were sent by George Edson to Hugh Middleton.

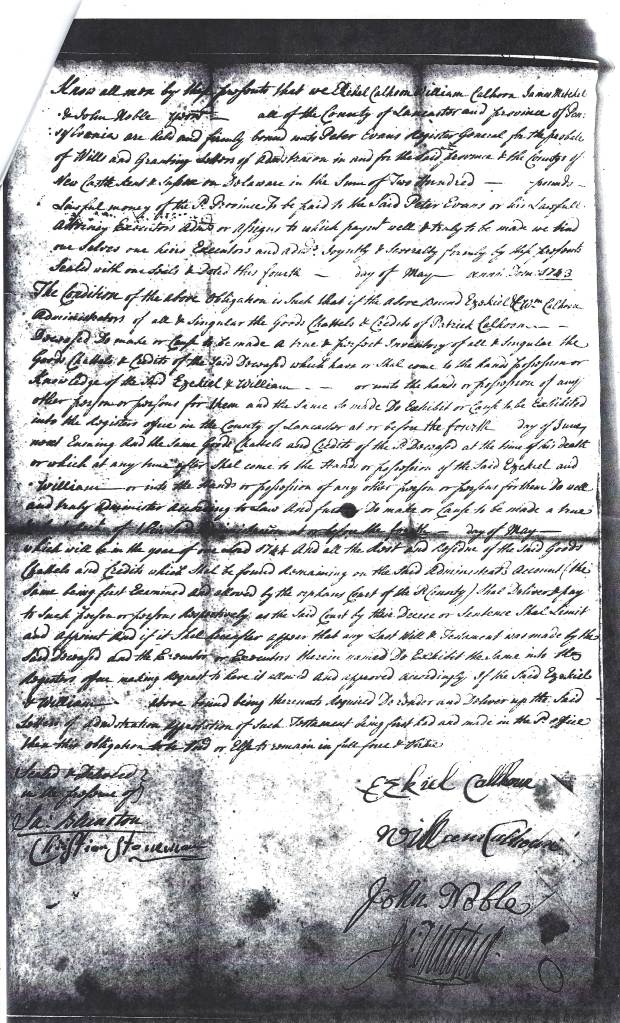

As the two postings linked in the preceding paragraph note, the documents found in Patrick Colhoun’s estate papers in Lancaster County include a relinquishment of estate administration by Patrick’s widow Catherine at an unspecified date – apparently in 1741 – to which is attached an inventory of his estate dated 1741; and a 4 May 1743 bond for administration of Patrick’s estate given by his sons Ezekiel and William Calhoun with their brother-in-law John Noble and with John Mitchell.

The widow Catherine’s relinquishment of administration to her sons Ezekiel and William appears to be written in her own hand and reads,

I do ketren Calhoun give over to the right of admoesternate to Ezekewl and Wilam Colihoun.

Preceding Catherine’s relinquishment of administration is an inventory of Patrick Calhoun’s estate made by James Small and John Williams. Underneath what Catherine has written someone writing in a different hand states that this document is an inventory of the goods and chattel of Patrick Calhown taken in 1741. The inventory shows Patrick’s estate consisting of four horses and a colt, six cows, five young cattle, nineteen sheep, swine, wagon gears, plows, and irons, “hosold” goods, and plantation tools. The plantation and crops in the ground were valued at £100, and the other items at £52 5 shillings, making a total of £152 5 shillings.[12]

The administration document shows Patrick Calhoun’s sons Ezekiel and William Calhoun giving bond for administration of the estate on 4 May 1743 in Lancaster County in the amount of £200 with their brother-in-law John Noble and James Mitchell. This document states that all parties lived in Lancaster County and is signed by each of those giving bond. Ezekiel appears to sign his name as Ezekiel Callhoun, and William as Willam Calhown (or perhaps Calhoun – the penultimate letter is hard to read).

According to A.S. Salley, final settlement of Patrick’s estate was made in Lancaster County on 4 May 1744, and as I’ve noted previously (here and here), following the estate settlement, Catherine and her children left Pennsylvania for Augusta County, Virginia, where they begin to appear in records by 8 October 1745.

The Significance of Patrick Colhoun’s Estate Documents

Patrick Colhoun’s estate documents are significant for a number of reasons. First, they establish that the immigrant ancestor of the Calhoun family that settled by March 1756 in the Long Cane region of the South Carolina upcountry was named Patrick and not James, as had long been thought. Unfortunately, a large number of researchers have chosen to handle that discovery by the incomprehensible choice to hobble together the names James and Patrick, turning this man into James Patrick Calhoun and even inventing mythical records in Northern Ireland of a man with that name who never existed, who is, they claim the “James Patrick” who went to Pennsylvania. The progenitor of the American Calhoun family I’m discussing here was plain Patrick, and in my view, he signed his name as Patrick Colhoun and not Calhoun, a point I’ll discuss in a moment.

[A side note here, but one not unrelated to the point I’ve just made: some years back, when I posted on an online genealogy thread the information I’ve just discussed about the estate records of Patrick Colhoun, someone begged to differ with my statement that he was named Patrick and not James Patrick. She told me she had a transcript of a baptismal register showing that Alexander Colquhoun (also Colhoun), pastor of the Church of Ireland parish of Clogherny in County Tyrone, had a son named James Patrick Colquhoun, who was, she maintained, the immigrant progenitor of the Calhoun family of the Long Cane settlement. I asked if she’d share that transcript with me. She then mailed me notes from a published history of some sort listing the children of Alexander Colquhoun/Colhoun, apparently citing a baptismal register. Written in handwriting and added to the printed text was an additional name: the name James Patrick. Someone had “corrected” the published text by penning in the name James Patrick.

In his study of the Calhoun family, Orval O. Calhoun states that he had located “notes” at Clogherny church showing that Alexander Colquhoun’s/Colhoun’s fourth son was one James Patrick Colquhoun – the man who emigrated in 1733 to Pennsylvania.[13] If such “notes” exist, I’d like to see them. In the meantime, I think it’s wiser to point to the ironclad proof we now have that the progenitor of the Calhoun family that settled in the Long Cane region in 1756 was one Patrick Calhoun – or as he signed himself, Patrick Colhoun. And I doubt very seriously that Patrick Colhoun, immigrant ancestor of the Calhoun family of the Long Cane, was a son of Alexander Colquhoun/Colhoun of Clogherny parish.]

A second reason the estate records of Patrick Colhoun are important: they are indubitably records of the immigrant ancestor of the Long Cane Calhoun family because we know with certainty that the mother of that family, whose grave her son Patrick Calhoun marked with a tombstone stating her name, was named Catherine, and we know from numerous sources that she had, among other children, sons named Ezekiel and William, the two men to whom Catherine Calhoun relinquished administration of Patrick’s estate in Lancaster County in or by 1741. The estate documents clearly signal that the estate for which the widow Catherine relinquished administration and which Ezekiel and William Calhoun administered is the estate of the immigrant ancestor of this family, Patrick Colhoun.[14]

Third, these documents tell us that Patrick Colhoun died in Lancaster County in 1740 or 1741. They pinpoint where this family settled after it emigrated from County Donegal, Ireland, to America in 1733. I’ve found no information corroborating W. Pinkney Starke’s claim that Patrick Colhoun and his family first arrived in New York and then went to Pennsylvania. Nor were the Calhouns living near the Potomac River in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, when they settled there, as Starke claims. The Potomac does not run through any part of Pennsylvania.

According to John C. Calhoun biographer Robert Elder, evidence suggests that when the Calhoun family (Elder calls them the Calhoons) arrived in Lancaster County, they settled in Drumore near Chestnut Level, almost certainly with friends and relatives.[15] I’m not sure what evidence Elder is citing, but it seems plausible that Patrick Colhoun and his family could have settled in Drumore near the Susquehanna River, a township named for Dromore in County Down, Ireland, where a Presbyterian church was established about a mile south of Chestnut Level prior to 1730 for settlers arriving in that part of Pennsylvania from Ulster.[16] The early records of that church have unfortunately been lost. Chestnut Level also happens to be where the Caldwell family into which Patrick Colhoun’s son Patrick married (his second wife was Martha, daughter of William Caldwell and Rebecca Parks) settled after arriving in America from Northern Ireland in 1727.[17] Martha Caldwell was the mother of John Caldwell Calhoun.

Noting that the family of Patrick Calhoun came to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in 1733 from County Donegal, Ireland, Robert Elder writes that crop failures in Ulster in the 1720s, combined with rising rents, falling linen prices, and political and religious oppression, created a perfect storm of pressures that led to the emigration of many Ulster Scots to America, which peaked in 1729 and continued for decades after that.[18] He also explains that another motivating factor for this emigration was religious and political persecution: Ulster Scots Presbyterians bridled at the system then in place forcing them to fund the Church of Ireland, and they were further unhappy that the Test Act of 1704 barred non-Anglicans from holding office in Ireland.[19]

Letters of John C. Calhoun Speaking of His Immigrant Grandfather

I mentioned previously (citing Brian Anton) that in some of his letters, Patrick Colhoun’s grandson John C. Calhoun stated – without naming his grandfather – that he, his wife, and children came to America in 1733 from County Donegal, Ireland. On 2 April 1845, writing from Fort Hill, South Carolina, to John Alfred Calhoun at Eufala, Alabama, John C. Calhoun said,[20]

I am now the last survivor of the first generation after the emigrants on my father’s side except Alexr Calhoun…. Our family on the father’s side emigrated in 1733….

And writing on 13 September 1841 to Gilbert C. Rice, secretary of the Irish Emigrant Society of New York, John C. Calhoun stated,[21]

I have ever taken pride in my Irish descent. My father, Patrick Calhoun, was a native of Donegal County. His father emigrated when he was a child. As a son of an emigrant, I cheerfully join your Society. Its object does honor to its founders.

These statements establish, then, that John C. Calhoun’s unnamed grandfather (Patrick Colhoun) left Ireland for America in 1733, and that the family came from County Donegal, where John C. Calhoun’s father Patrick Calhoun was born in 1727.

Patrick Colhoun’s Signature in Tillotson’s Book of Sermons

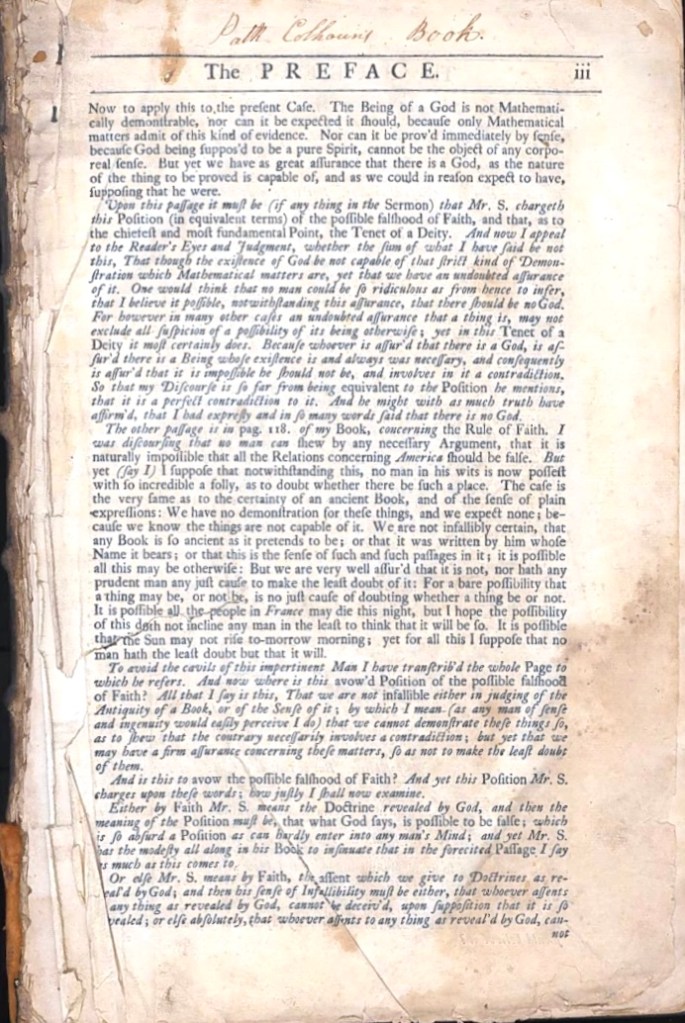

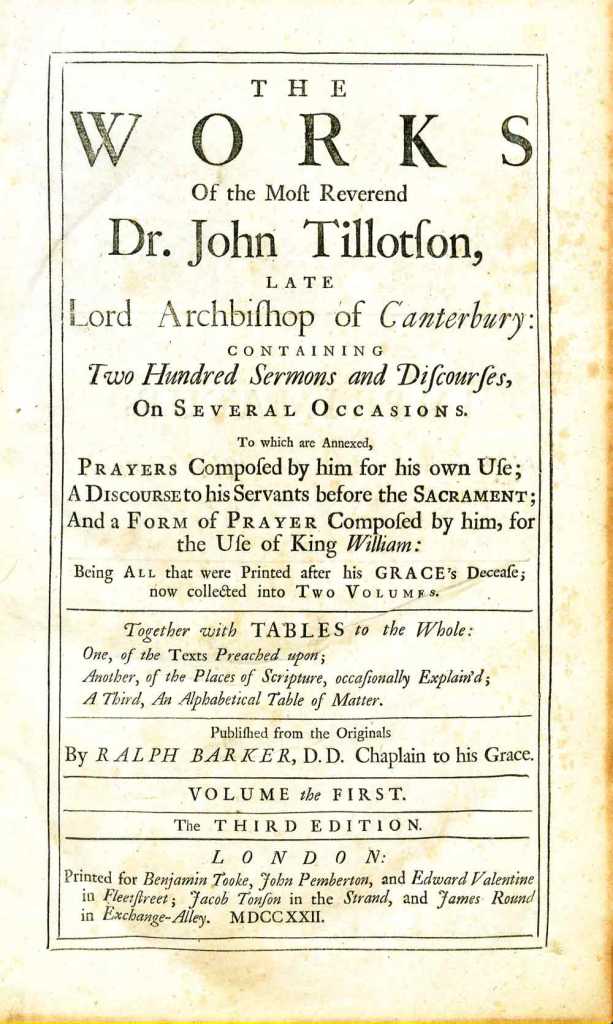

One other precious artifact has passed down from Patrick Colhoun the immigrant ancestor (as I conclude along with others), capturing his signature and showing him signing his name as Patrick Colhoun. This signature is in a book of sermons by Anglican bishop John Tillotson printed in 1727 and now owned by the South Carolina Department of Archives and History. The book is missing its title page. Its contents show that it’s a copy of The Works of the Most Reverend Dr. John Tillotson, Late Lord Archbishop of Canterbury, a collection of sermons preached by Tillotson in the period 1680-8. A handwritten frontispiece in the book evidently inserted when it was given to the archives and written by A.M. Aiken states that it was printed in London in 1727. At the top of page iii of this book, in its preface, is written the inscription, “Patk. Colhoun’s Book.”

A.M. Aiken’s frontispiece says that the book passed from Patrick Calhoun, father of John C. Calhoun, to John C. Calhoun, who gave it in 1836 to Colonel M.O. Tollison for the Greenwood Library, who then gave it to General James Gilliam, a Caldwell cousin to John C. Calhoun. General Gilliam gave the book to Mary Gilliam Aiken, wife of A.M. Aiken, who gave it to the South Carolina archives. A.M. Aiken’s frontispiece is dated 4 May 1896. In this document, he states (erroneously) that the signature on page iii is that of Patrick Calhoun, father of John C. Calhoun.

The catalogue description of Tillotson’s book of sermons at SCDAH says that the book was actually presented to the archives on 23 April 1906 by Dr. Hugh Aiken. The catalogue description, which catalogues the book as “Sermons” with Tillotson, John as its author, states,

This printed book of sermons, which is missing its title page, bears the signature of Patrick Calhoun, the father of John C. Calhoun. An inscription inside the cover details its provenance and says that the volume was printed in London in 1727.

Notes written by South Carolina genealogical researcher Leonardo Andrea and preserved in one of the Calhoun folders of his Leonardo Andrea Collection state that Andrea had seen this book, and that it was clear to him that the signature did not match that of Patrick Calhoun, father of John C. Calhoun, or of other Patrick Calhouns of later generations in this Calhoun family.[22]

Because the Patrick Calhoun (1727-1796) who was the son of Patrick the immigrant and father of John C. Colhoun surveyed many plats of land for early settlers of the South Carolina upcountry, and because those plats bear his signature, the signature of that Patrick is easy to find, and clearly does not match the signature found in this volume of Tillotson sermons printed in 1727. In his must-read article discussing Patrick Colhoun at his Genealogy of the Calhoun Family site, Brian Anton places the signature found in the Tillotson book next to that of Patrick Calhoun, son of John C. Calhoun. The difference in the two signatures is clearly apparent.

I’m calling the inscription in the volume of Tillotson sermons – “Patk. Colhoun’s Book” – a signature because it was very common in the period in which the book was printed for book owners to write their names at the front of a book, often with the name of the owner followed by “his book.”[23] My conclusion about this inscription concurs with that made by Leonardo Andrea: this inscription is the signature of Patrick Colhoun, the immigrant progenitor of the Calhoun family that settled in the Long Cane region of South Carolina in 1756. Given that this book was published in 1727 and we know that the immigrant Patrick died in 1740 or 1741 in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, it makes sense, I think, to conclude that that this book very likely belonged to that immigrant Patrick.

And because we know from A.M. Aiken’s frontispiece that the book passed from that Patrick’s son Patrick to his son John C. Calhoun and then down through the Gilliam and Aiken families – a chain of transmission of which A.M. Aiken was aware, it appears, through his wife Mary Gilliam Aiken – I think it’s also very likely that this book passed initially from Patrick Colhoun the immigrant to Patrick Calhoun his son and from the second Patrick to his son John C. Calhoun.

It would be ideal if we could compare this signature with another of Patrick Colhoun the immigrant. Unfortunately, I haven’t seen any document bearing Patrick Colhoun’s signature that has been discovered. His estate documents in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, have, it’s clear to me as stated previously, the signature of his wife Catherine (spelling her name as ketren) and of their sons William and Ezekiel, along with the signature of William and Ezekiel’s brother-in-law John Noble. But they do not have any signature of Patrick himself.

[It’s worth noting that these documents show that the first and second generation of the Colhoun/Calhoun family of County Donegal who settled in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, were literate, insofar as they could sign their names – and other documents show the children of Patrick and Catherine Colhoun, especially their sons, as more than minimally literate. As historians have frequently noted, literacy rates in post-Reformation Scotland (and among Scottish settlers of Ulster) seem to have been solid, because Presbyterianism prized the ability of lay believers to read the Bible.[24] As David Hackett Fischer notes, the family descending from Patrick and Catherine Calhoun/Colhoun also belonged to the group of Ulster Scots settlers that Fischer classifies as the “backcountry ascendancy,” people who brought from Ulster a certain social standing that enabled them to rise quickly to leadership positions in the colonies.[25] These families tended to be more than commonly literate, with educational levels for their male members especially that contributed to their quick rise to leadership in the colonies.]

The signature of Patrick Colhoun in the book of Tillotson sermons seems to me to be the signature of a man with more than minimal literacy. I cannot by any means claim to be an expert in the history of handwriting, but I’m also inclined to think the signature is in a style more typical of the 18th than of the 19th century. I’d say it’s clearly a signature written with a quill pen. I’m aware that the use of quill pens continued into the 19th century before metal pens overtook them. To my untrained eyes, the signature strikes me as one more likely made in the 18th than in the 19th century.

The fact that this Patrick seems to have signed his name as Colhoun instead of Calhoun also seems to me worth noting. Since I am persuaded that the man signing his name in the book of Tillotson sermons is Patrick the immigrant, then I’d note that if this conclusion is correct, the immigrant ancestor of this Calhoun family signed his surname as Colhoun, a spelling closer to the Scottish original, Colquhoun, than the Calhoun spelling is. Colhoun is, in fact, a phonetic rendering of Colquhoun. Legends have developed around the fact that Patrick’s grandson John Ewing Colhoun, son of Ezekiel Calhoun, also used the Colhoun spelling; there’s a mythic idea that a noble member of the Scottish Colquhoun family convinced John Ewing Colhoun to adopt this spelling, because it was closer to the Scottish original. In my view, if we conclude that John E. Colhoun’s grandfather Patrick used the Colhoun spelling, then it would appear that his grandson John E. Colhoun used that spelling because his grandfather did so. As I’ve also shown, John Ewing Colhoun’s brother Ezekiel used the Colhoun spelling as well.

Unanswered Questions about Patrick Colhoun’s Irish Roots

To date, no documents showing where in County Donegal this Colhoun family lived prior to emigrating to America in 1733 have come to light – at least, insofar as I’m aware. A.S. Salley thought that a Hugh Colhoun who made his will in Charleston District, South Carolina, on 30 November 1792, stating that he was of Fawny, County Tyrone, Ireland, was a Hugh Calhoun who is found with members of the Patrick Colhoun family after that family moved to Augusta County, Virginia, and then to the Long Cane region of South Carolina.[26] Salley states,[27]

This Hugh Colhoun, who, in 1777, lived in the same neighborhood with Patrick, William and James Calhoun, made his will, Nov. 30, 1792, and recited that he was of “Fawny, County Tyrone, and Kingdom of Ireland, Farmer (but now in America, State of South Carolina, and Parish of Saint James’s Santee, Charleston District);” mentioned his wife Jane, sons John, James, William and an unnamed son, and daughters Sarah and Elizabeth, and brother John. The following notice probably concerns this last John:

“Departed this life on the 24th June, in St Andrew’s Parish, near Charleston, So. Ca. Mr. John Calhoun, formerly of Bushfield, L. Derry, Ireland.” City Gazette and Commercial Daily Advertiser, Sat., July 11, 1829.

If Salley is correct in identifying the Hugh Calhoun of the November 1792 Charleston District will as the Hugh Calhoun who lived in the Long Cane settlement in Abbeville County, then this will and the death notice of John Calhoun that he cites in discussing this will would be clues to the place of origin of Patrick Colhoun’s family in Ireland. Fawney is a townland in County Tyrone about ten miles south of Derry.

In his biography of John C. Calhoun, William Montgomery Meigs cites Salley as Meigs also identifies the Hugh Colhoun of the November 1792 Charleston District will with the Hugh Calhoun who settled with members of the Patrick Colhoun family in the Long Cane settlement.[28] Meigs also notes the 11 July 1829 death notice of John Calhoun, formerly of Bushfield, County Derry, cited by Salley.

To complicate matters further, Lewin Dwinnell McPherson turned the 11 July 1829 death notice of John Calhoun cited by Salley (and Meigs) into a death notice of John C. Calhoun published in a Washington, D.C., newspaper in 1850, which stated that his father Patrick Calhoun was born in Bushfield, County Derry, Ireland.[29] McPherson concludes – on what basis is not clear to me – that the Patrick Colhoun family emigrated from “the vicinity of Portlough in Co. Donegal, Ireland,” adding, “Portlough is in the Laggan District at the Londonderry county.”[30]

This is a mishmash of misinformation, and it begins with an assumption that is, in my view, simply not correct: namely, that the Hugh Colhoun who wrote his will on 30 November 1792 in Charleston District, South Carolina, stating that he was from Fawny (i.e. Fawney) in County Tyrone, Ireland, was the Hugh Calhoun living among members of the Patrick Colhoun family in the Long Cane settlement of what became Abbeville County. In my view, that Hugh Calhoun who was, I think, very likely a relative of the Patrick Colhoun family, died testate in Abbeville County before 25 March 1799 with a will dated 25 August 1794.[31] Hugh’s will, which he signed and which was witnessed by William Dunlap, Alexander Noble, and Archibald McClene, names wife Jennett and children, Hugh, Ezekiel, and Mary (Morrow). It names among other executors James Noble. Alexander and James Noble were sons of Patrick Colhoun’s daughter Mary and her husband John Noble. One of the appraisers of Hugh Calhoun’s estate was Ezekiel Colhoun, son of Ezekiel Calhoun and Jean/Jane Ewing, whose sister Catherine married her cousin Alexander Noble.

In short, I’m not aware of any solid information that has been found to date pinpointing the Irish place of origin of Patrick Colhoun and his family, other than the statement of John C. Calhoun in his 13 September 1841 letter to Gilbert C. Rice cited previously that his father Patrick Calhoun was born in County Donegal, Ireland.[32] The tombstone of Patrick Calhoun in the Calhoun cemetery in Abbeville County, South Carolina, gives his birthdate as 11 June 1727 and also states that he was born in County Donegal, Ireland.[33]

Mary B. Kegley provides biographical information about a James Montgomery who appears to have come with the Calhouns from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, to Augusta County, Virginia, and died there in 1756, and who is thought to have been a brother of Patrick Colhoun’s wife Catherine Montgomery.[34] Kegley states that James Montgomery came with his family to America in 1733 from County Donegal, Ireland. If this is correct, then I’d conclude that James and perhaps other members of the Montgomery family came from County Donegal to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in 1733 with the Patrick Colhoun family. Perhaps research on the Irish origins of this Montgomery family that was closely connected to the family of Patrick Colhoun may eventually provide more clues about where in County Donegal both of these families lived prior to emigrating to America.

[1] Brian Anton, “Two Middle Names That Aren’t,” Genealogy of the Calhoun Family.

[2] William Pinkney Starke, “Account of Calhoun’s Early Life, Abridged from the Manuscript of Col. W. Pinkney Starke,” in Correspondence of John C. Calhoun, ed. J. Franklin Jameson (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1900), pp. 65-89.

[3] Ibid., p. 65.

[4] “Publications Received,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 2,2 (April 1901), p. 159.

[5] The initial article in this series was A.S. Salley Jr., “The Calhoun Family of South Carolina,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 7,2 (April 1906), pp. 81-98.

[6] See supra, n. 1.

[7] William Montgomery Meigs, The Life of John C. Calhoun (New York: Neale, 1917), p. 32.

[8] See supra, n. 1.

[9] Zella Armstrong, Notable Southern Families, vol. 1 (Chattanooga: Lookout, 1918), p. 46.

[10] A.S. Salley, “The Grandfather of John C. Calhoun,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 39,1 (January 1938), p. 35.

[11] These original estate documents are evidently filed in Lancaster County’s letters of administration for estates: the county’s index to letters of administration, 1730-1830, which is available digitally at FamilySearch, contains a listing of the estate of Patrick Calhoun dated 1743. A prefatory note on the index states, “All adms. granted previous to 1821 can be found filed with The Bonds in Recorder Office at Lancaster.” The FamilySearch collection of Lancaster County probate records does not include letters of administrations or bonds. There is no listing of Patrick Colhoun’s estate in the county index to wills, 1739-1947.

[12] On these estate documents, see also Mary B. Kegley, Early Adventurers on the Western Waters, vol. 3, pt. 2 (Marceline, Missouri: Walsworth, 1995), pp. 597-8; Calhoun folder no. 128 (p. 2) in the Leonardo Andrea Collection; and Salley, “The Grandfather of John C. Calhoun.”

[13] Orval O. Calhoun, 800 Years of Colquhoun, Colhoun, Calhoun, and Cahoon Family History, vol. 4 (Baltimore: Gateway Press: 1991), p. 44.

[14] Lewin Dwinnell McPherson reports in his Calhoun, Hamilton, Baskin and Related (privately published, 1957) that, after George Edson’s discovery of Patrick Calhoun’s estate papers “corrected the long outstanding publications and/or traditions that this immigrant Calhoun was named James,” Calhoun Mays of Greenwood, South Carolina, then exhibited photocopies of the estate proceedings at a family gathering in Columbia to prove to Calhoun descendants that the immigrant ancestor was named Patrick (p. 9).

[15] Robert Elder, Calhoun: American Heretic (New York: Basic, 2021), pp. 1-4.

[16] See Franklin Ellis and Samuel Evans, History of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, with Biographical Sketches of Many of Its Pioneers and Prominent Men (Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1883), pp. 789f.

[17] In an 11 May 1825 letter, John Rodgers, a grandson of John Caldwell, the immigrant ancestor of this family, states that the Caldwell family left Ireland in 1727, landing at Newcastle, Delaware, and then settling at Chestnut Level in Pennsylvania: the letter is transcribed in Elizabeth Venable Gaines, Cub Creek Church and Congregation 1738-1838 (Richmond: Whittet & Shepperson, 1931), pp. 90f. Patrick Calhoun’s wife Martha Caldwell was a granddaughter of John Caldwell, who is thought to have come from County Derry, Ireland.

[18] Elder, Calhoun: American Heretic, p. 3.

[19] Ibid., pp. 1-2.

[20] The Papers of John C. Calhoun, vol. 21: 1845, ed. Clyde N. Wilson (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1993), p. 465. Robert Elder cites this letter in his Calhoun: American Heretic, p. 439, noting that John Alfred was a son of John C. Calhoun’s brother James, whose widow Sarah Caldwell Martin Calhoun had died on 11 March 1845.

[21] The Papers of John C. Calhoun, vol. 15: 1839-1841, ed. Clyde N. Wilson (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1983), p. 774.

[22] Leonardo Andrea, Calhoun folder no. 128 in the Leonardo Andrea Collection.

[23] Women certainly owned books, too, but men were more likely to be literate in this period in colonial America and the British Isles.

[24] See e.g. James C. Leyburn, The Scotch-Irish: A Social History (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1962), pp. 212–13; David Hackett Fischer, Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), pp. 645–46; Arthur Herman, The Scottish Enlightenment: The Scots’ Invention of the Modern World (New York: Random House, 2001); William R.Hoyt, “Presbyterianism,” in Encyclopedia of Religion in the South, ed. Samuel S.Hill (Macon: Mercer University Press, 1984), pp. 607–11; and Charles Reagan Wilson,“Religion and Education,” in Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, ed. CharlesReagan Wilson and William Ferris (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press,

1989), p. 262.

[25] Fischer, Albion’s Seed, pp. 644-7. On the Patrick Colhoun family as “in many ways typical of the more prosperous families that joined the great migration through the Shenandoah Valley into the backcountry of the Carolinas,” see Rachel N. Klein, Unification of a Slave State: The Rise of the Planter Class in the South Carolina Backcountry, 1760-1808 (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1990), p. 17. Klein notes that in the South Carolina backcountry, Patrick Calhoun, his son John C. Calhoun, and his nephew John Ewing Colhoun all quickly rose to leadership positions along with Andrew Pickens, who married John E. Colhoun’s sister Rebecca (see pp. 11, 13, 26-7, 139-141). Klein states, mystifyingly, that the Calhouns came from County Donegal, Ireland, to Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and then moved with the unnamed father of the family to Augusta County, Virginia, where the immigrant father died (p. 17).

[26] A.S. Salley Jr., annotator, “Journal of William Calhoun,” Publications of the Southern History Association 8,3 (May 1904), p. 186, n. 11.

[27] “Publications Received,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 2,2 (April 1901), p. 160.

[28] Meigs, The Life of John C. Calhoun, p. 33.

[29] McPherson reports in his Calhoun, Hamilton, Baskin and Related, p. 8.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Abbeville County, South Carolina, Will Bk. 1, p. 227; Loose-Papers Estate Files, box 18, pkg. 387.

[32] See supra, n. 21.

[33] See Find a Grave memorial page for Patrick Calhoun, Calhoun cemetery, Abbeville County, South Carolina, created by David Gillespie, with a tombstone photo by David Gillespie.

[34] Kegley, Early Adventurers on the Western Waters, vol. 3, pt. 2, pp. 722-6.

Excellent article as always. One note: The Hugh from Fawney, Tyrone, Ireland and Charleston, SC makes his will in Nov. of 1792 and it’s probated in Nov 1792 according to the original will in the experiments section of Family Search. His children are James, John, William, Sarah and Elizabeth. The Hugh of Abbeville, has his will probated in 1799 and has some of the same names in his children but additional / differing ones also like Ezekial. I’d pass along the link for the 1792 will but that is the frustrating part of Family Search. One has to log in and then find the record for oneself at my last check on that. Thanks for your detailed work!

LikeLike

I need to make a correction from memory. When I doublechecked Hugh’s 1792 will of Charleston, SC, it was probated in Mar. of 1798. Here is a link to his will on Ancestry. https://www.ancestry.com/imageviewer/collections/9080/images/004753757_00036

LikeLike

Thank you for your helpful comments and for the link to Hugh Colhoun’s 1792 will. You’re right that it was proved in 1798. I’m fairly confident that the Hugh Colhoun of this will is not the Hugh Calhoun who made his will in August 1794 in the Long Cane settlement. It seems to me very likely that that Hugh living in the Long Cane settlement was a close relative of the other Calhouns living there. I can’t say I’m certain that the Hugh Colhoun who made his will in 1792 is closely related to the Calhoun family in the Long Cane settlement. The problem here is that some researchers seem to have conflated two different Hughs — or so it appears to me.

LikeLike