In 1755, the Calhoun family left Virginia for the Long Cane region of what eventually became Abbeville County, South Carolina, where they settled in February 1756, and Ezekiel and his siblings acquired land there — the second posting linked above discusses Ezekiel’s land acquisitions in South Carolina in detail, and the first linked posting discusses his land purchases in Virginia. At the end of his life, Ezekiel returned to Augusta County, Virginia, on business and was shot and killed there by an unidentified assailant and buried on his land on Reed Creek in what is now Wythe County, Virginia.

In this posting, I’ll begin to share the information I have about the children of Ezekiel Calhoun and Jean Ewing. As a previous posting states, in the will he made in South Carolina on 3 September 1759, Ezekiel names his sons and daughters in two separate lists, the boys first and girls second, and by order of birth (i.e., each list names the names in the order of their birth).[2] The will states that Ezekiel had sons John, Patrick, and Ezekiel, and daughters Mary, Rebecca, Catherine, and Jean. Evidence that I’ll note as I discuss each of these children allows us to arrange Ezekiel’s children in the following order of birth: Mary, Rebecca, John Ewing, Catherine, Patrick, Ezekiel, and Jean.

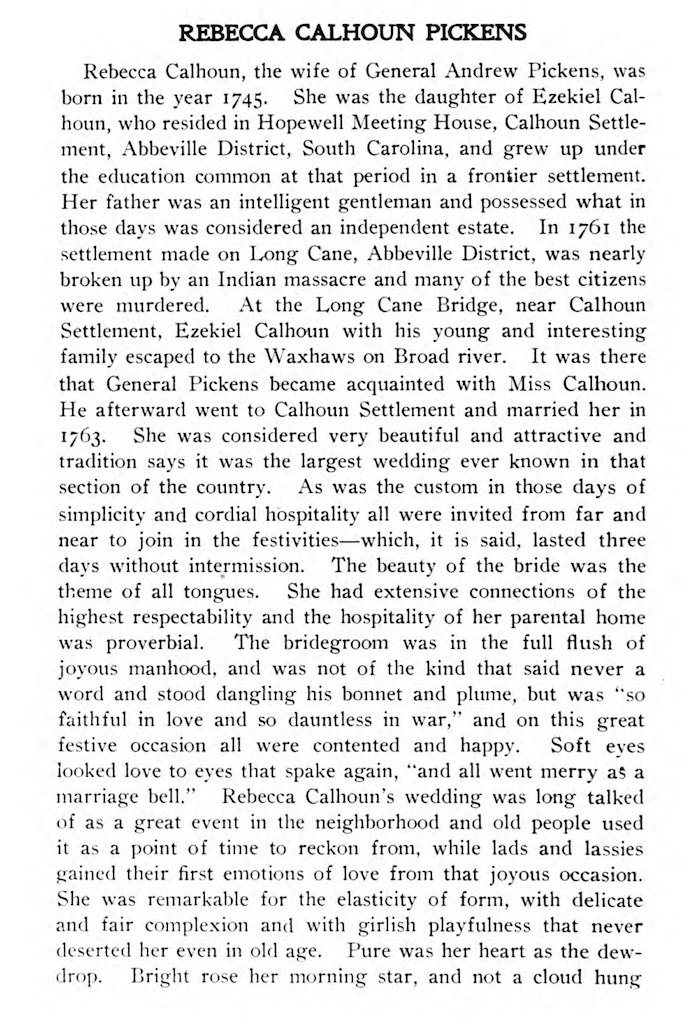

I’ve discussed Ezekiel and Jean Ewing Calhoun’s oldest child, Mary (who is my ancestor), in detail in a previous posting, which places her birth around 1743 and provides my reasons for assigning that birth year to Mary. Now I’d like to share with you what I know about the next of Ezekiel and Jean’s children, their daughter Rebecca. I will not be providing exhaustive accounts of these Calhoun children, several of whose lives are already well-documented in numerous published histories readily available online and in published accounts.

Rebecca Calhoun

The posting about Mary Calhoun Kerr that I’ve just linked in the previous paragraph states that Mary’s sister Rebecca was born 18 November 1745. The posting provides a digital image of Rebecca’s tombstone in the Old Stone Church cemetery at Clemson in Pickens County, South Carolina, which has this date of birth stated on it.[3] As the posting linked above also states, though the Find a Grave memorial page to which the photo of Rebecca’s tombstone points, as well as a number of published family histories, state that Rebecca Calhoun had the middle name Floride, I have seen no evidence that she had any name other than Rebecca. The name Floride came into the Calhoun family when Rebecca’s brother John Ewing Colhoun married Floride Bonneau, a woman of French Huguenot descent, on 8 October 1786. For reasons unfathomable to me, some sources have decided to take the given name of the wife that John E. Colhoun married 41 years after his aunt Rebecca Calhoun was born, and to add it to Rebecca’s name — when that French name was never used in the Ulster-Scots Calhoun family until after John E. Colhoun married Floride Bonneau.

Numerous family trees found online have also borrowed a portrait of John E. Colhoun’s daughter Floride Bonneau Colhoun, who married her cousin John Caldwell Calhoun, and placed it in their family trees, and have plopped that portrait into their family trees, claiming that it is a portrait of Rebecca Calhoun Pickens.[4] It’s not. It’s a portrait of her niece Floride Bonneau Colhoun Calhoun. On this point, see this subsequent posting.

The inscription on Rebecca Calhoun Pickens’ tombstone reads,

In memory of Rebecca Pickens, who was born on the 18th Nov. 1745, died on the 19th Dec. 1814, She was through life religious & charitable, died humbly relying on the mercy of her Redeemer

The tombstone is dated — 1 March 1815 — and I think it’s likely it was erected by Rebecca’s husband Andrew Pickens, who is buried with her in the Old Stone Church cemetery at Clemson. Both have white marble grave markers that, while not identical, are still very similar in form and style. A 7 March 1818 receipt in the F.W. (Francis Wilkinson) Pickens Papers at Duke University’s Rubenstein Library shows Rebecca’s cousin John Noble being paid on that date by Andrew and Rebecca Pickens’ son Andrew Pickens (1779-1838) for a marble tombstone in memory of General Andrew Pickens, Rebecca’s husband.[5] Andrew Pickens died 11 August 1817, so his grave was marked not long after his death with a marble tombstone similar to the one marking Rebecca’s grave, which we know from the date inscribed on Rebecca’s tombtone was placed at her grave not long after she died. Francis Wilkinson Pickens was, by the way, a son of Andrew and Rebecca Calhoun Pickens’ son Andrew, who paid for his father’s marble tombstone.[6]

Since, as a previous posting indicates, Rebecca’s parents Ezekiel and Jean Ewing Calhoun had arrived on Reed Creek in Augusta (later Wythe) County, Virginia, by 1745, if Rebecca was born on 18 November 1745, then she would have been born in Virginia following her parents’ removal there from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.

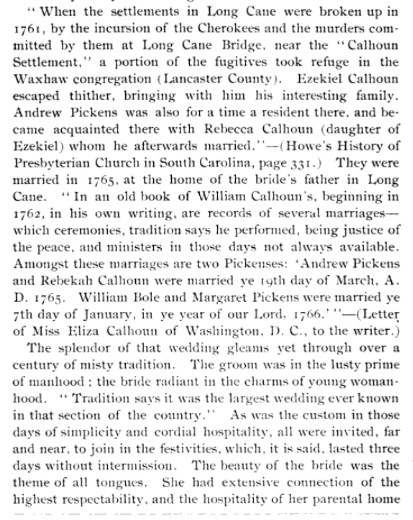

Following the Calhoun family’s move from Augusta County, Virginia, in 1755 to the Long Cane area of what was then Granville County, South Carolina, and later became Abbeville County, Rebecca’s name appears in Calhoun chronicles when the Long Cane massacre occurred on 1 February 1760. As the last posting notes, according to historian Bobby Edmonds, Rebecca survived the Cherokee attack on the Long Cane settlers by hiding among canes and then concealing herself in the woods until her uncle Patrick Calhoun found her when he returned to the massacre site the following day to look for survivors.[7] A similar story is told in William R. Reynolds’ biography of Andrew Pickens, which states the following:[8]

Fourteen-year-old Rebecca Calhoun, daughter of Ezekial [sic], successfully hid herself in some reeds during the massacre, and later in a calico or kalmia bush. From there she watched the slaughter and saw her grandmother, Catherine Calhoun, murdered and scalped.

Curiously, I have not found sources close to the Long Cane massacre itself recounting this story of Rebecca’s hiding during the massacre, nor am I clear about the documentation being cited by recent historians who share this story. I’ve followed the documentation offered by both Edmonds and Reynolds without finding a clear source close to the date of the massacre itself that might have preserved this chronicle.[9] Several accounts of the massacre appeared in the South Carolina Gazette almost immediately following these events — these newspaper reports have been helpfully transcribed at the Long Cane Webpage site at Rootsweb — but none of these contain information about Rebecca Calhoun hiding out during the massacre.[10] Nor does the letter that Rebecca’s grandson Francis Wilkinson Pickens wrote on 26 March 1848 to Charles H. Allen (it has been discussed previously), which provides information about the Long Cane events and the relocation of Rebecca’s family to the Waxhaws following the massacre, say anything about these matters.[11]

The earliest mention I’ve found of Rebecca Calhoun hiding in a cane brake during the massacre and then being found three days later by her uncle Patrick Calhoun is in William Pinkney Starke’s manuscript about the life of John C. Calhoun composed between 1883-6. An abridged version of this manuscript was published by J. Franklin Jameson in 1899 in his Correspondence of John C. Calhoun (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1899). In this manuscript, Starke states (p. 68),

When Patrick Calhoun and others returned to bury the dead three days afterwards, he discovered his niece Rebecca, who had concealed herself in the cancbrake.

In his The Life of John Caldwell Calhoun, vol. 1 (New York: Neale, 1917), William Montgomery Meigs repeats this story (p. 39), not naming the uncle of Rebecca who found her following the massacre, and prefacing his account by noting that he’s relying on Starke’s manuscript, though he adds that Starke provides certain details about the massacre “unfortunately without giving any authority.” William Pinkney Starke grew up in the “Calhoun region,” and my understanding is that his manuscript relied to some degree on oral traditions handed down in that region.

As a previous posting states, in his letter to Charles Allen, Francis W. Pickens states,

After [the Long Cane Massacre, Ezekiel Calhoun fled to the Waxhaws, the nearest white settlement, for protection.

My grandfather [i.e. Andrew Pickens] lived there, and then got acquainted with my grandmother [i.e., Rebecca Calhoun], who was the daughter of Ezekiel Calhoun, and came back to the Calhoun’s settlement with them, and married there.

Francis Pickens goes on to state,

He [i.e., Andrew Pickens] then settled there in 1764, but in 1765 he moved to and settled at the place where the Block House is standing near Abbeville C.H. [i.e. courthouse]. He built the Block House about 1768—perhaps 1767—and made it a resort for the neighbors to fly to in order to protect themselves from the Indians, he always taking command. He owned all the lands about the place where the present village [i.e., Abbeville] stands, and I think sold to Maj. Hamilton, who was also a gallant soldier of the Revolution.

The story of Andrew Pickens and Rebecca Calhoun meeting when her family fled from the Long Cane settlement to the Waxhaws settlement on the North Carolina-South Carolina border after the Long Cane massacre appears in multiple accounts following Francis W. Pickens’ March 1848 letter.[12] The importance of this meeting is that Andrew Pickens and his family were living in the Waxhaw settlement at this point, having come there in 1752 or 1753 from Augusta County, Virginia, to which his father, also named Andrew Pickens, had brought the family from Paxtang (later called Paxton) township in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, when Andrew Jr. was young. In a letter he wrote to General Henry (“Light Horse Harry”) Lee on 28 August 1811, Andrew Pickens states,[13]

I was born in Pennsylvania, Paxton township, on the 19th Sept. 1739; my father removed with his family when I was very young, to Virginia and settled for a few years West of where Staunton now stands about 8 miles, and in the year 1752 or 3 removed to the Waxhaws & was amongst the first settlers of that part of South Carolina.

One biography after another including Andrew Pickens’ obituary in the Pendleton Messenger on 27 August 1817 places his birth in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and not Lancaster County. It’s true that prior to moving to Lancaster County, his family lived in Bucks County. Paxtang township was in Lancaster County and not Bucks County, so if Andrew’s own testimony about where he was born is to be taken seriously, it’s clear he was born in Lancaster and not Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Paxton township (as the township is now called) is now in Dauphin County contiguous to Lancaster.

Andrew Pickens goes on to tell General Lee that his parents had come to Pennsylvania from Ireland and that, his father’s progenitors had come from France, a statement that has misled many family historians and researchers to conclude that the Pickens family is French in origin and to speak of Andrew Pickens as a Huguenot. Andrew Pickens was not a Huguenot. Like the Calhoun family, the Pickens family is a Scottish family[14] that had made its way to Ulster before coming to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania (note the close parallels with the migration process of the Calhoun family, from Ireland to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, to Augusta County, Virginia, to the South Carolina upcountry) — though there are some indicators that, back in time, a member of the Pickens family spent time in France, a nation to which Scotland long had very close cultural and political ties.

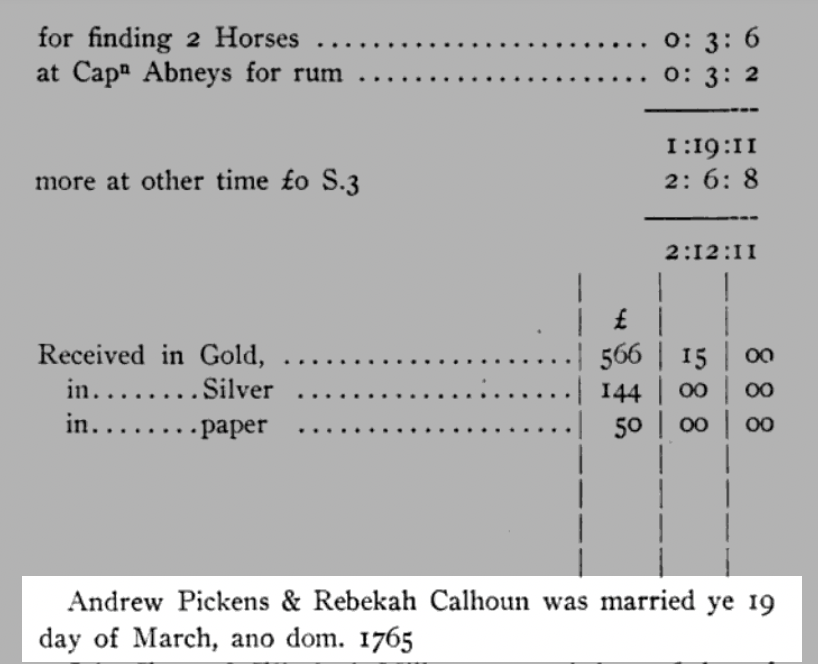

As a previous posting has noted, in a journal that Rebecca Calhoun’s uncle William Calhoun kept, which served as a ledger for his store in the Long Cane settlement and a repository of family notes in the period 1760-1770, William Calhoun recorded the date of his niece Rebecca Calhoun’s marriage to Andrew Pickens:[15]

Andrew Pickens & Rebekah Calhoun was married ye 19 day of March, ano dom. 1765

A majority of the accounts[16] of Andrew Pickens and Rebecca Calhoun’s meeting in the Waxhaws after her family went there following the Long Cane massacre on 1 February 1760, when she was fourteen and he twenty, contain accounts of their wedding, with no sources that I’ve been able to turn up cited for these accounts. These say that the wedding at the bride’s home in the Long Cane settlement was “the largest wedding ever known in that section of the country,” that “the beauty of the bride was the theme of all tongues,” and that the marriage was “long talked of as a great event in the neighborhood and old people used it as a time to reckon from, while many lads and lassies dated their first emotions of tenderness and love from that joyous occasion.” I’m quoting here from James Henry Rice’s 1895 account in American Monthly Magazine.[17] The same account is found almost verbatim in other sources like Mrs. S. Bleckley’s 1910 account in the same magazine, or Monroe Pickens’ narrative in his history of the Pickens family.[18]

As with the story of Rebecca Calhoun hiding in a cane brake during the Long Cane massacre, I wonder where these stories came from, and what “the largest wedding ever known” in the sparsely settled South Carolina upcountry might have looked like in a settlement ravaged only five years earlier by a Cherokee attack…. Please note: my intent is not to ridicule or discount testimony about either Rebecca’s experience during the Long Canes massacre or her wedding. It’s just to ask why there seem to be no documented sources close in time to these events, on which the curiously detailed accounts provided by later writers might be relying. Or perhaps I have just not discovered those sources….

Note that Rice’s story about Rebecca Calhoun’s marriage says that she and Andrew Pickens married “at the home of the bride’s father in Long Cane,” but, as we’ve seen previously, Rebecca’s father Ezekiel Calhoun died prior to her marriage in 1765. His will was probated on 25 May 1762, after he was shot and killed at a cabin on his land in Augusta County, Virginia. As the posting I’ve just linked states, soon after Ezekiel’s death, his widow Jean Ewing Calhoun remarried to Robert Norris. So it seems to me that in all likelihood, Rebecca’s marriage to Andrew Pickens in the Long Cane settlement would have taken place at the home of her step-father Robert Norris and her mother Jean Ewing.

As does James Henry Rice in his stories of the wedding of Andrew and Rebecca, various biographical accounts wax florid in describing Rebecca’s appearance and character. Mrs. S. Bleckley states,[19]

She was remarkable for the elasticity of form, with delicate and fair complexion and with girlish playfulness that never deserted her even in old age. Pure was her heart as the dewdrop. Bright rose her morning star, and not a cloud hung around it. Ah! how little did her young heart know of the trials and dangers that lay before her in the future!

And — more elasticity! — she adds,[20]

With elasticity of spirits, remarkable even in one of her sex, she had the peculiar faculty of government over her children, who feared and loved her. Her sons often spoke of her in after life; her house was the delight of the young people, and her playful spirits enlivened their evening sports.

The Bleckley biography concludes,[21]

In all the genuine dignity that becomes a woman, in love and affability of deportment, in gentleness and kindness of disposition and manners, Mrs. Andrew Pickens had few equals—while in all the pure and high virtues which adorn the female character, she had no superiors.

Again, please don’t misunderstand me: I would certainly want to assume that Rebecca Calhoun Pickens was a woman of admirable character and virtue. It took fortitude, ingenuity, and creativity for these pioneers in the South Carolina upcountry to thrive, and thrive Rebecca and many of her Calhoun kin surely did, as did members of the Pickens family. Still, I wonder where some of these seemingly legendary stories, full of fulsome embellishment that makes their characters quasi-mythic figures, originated, and when they originated.

Lewin Dwinnell McPherson also places Rebecca on a pedestal in his account of the Calhoun and related families, noting that Rebecca Calhoun Pickens was “one of the best educated and most gifted ladies of the day.”[22] As my posting about Rebecca’s sister Mary Calhoun Kerr notes, commenting on a 3 August 1793 letter she sent to her brother John Ewing Colhoun, Ezekiel Calhoun’s daughters definitely appear to have been literate, and that cannot be said for many other women in the Southern colonies during their time frame, including women of high social status.[23] The Scottish culture that the Calhouns and allied families brought to the American colonies placed high value on literacy, including for women, because it took reading the bible seriously.[24]

But I suspect it’s quite an exaggeration to claim that Rebecca Calhoun Pickens was “one of the best educated” women of her period. Even when they were taught to read and write, Southern women of their time and place, including ones of high social status, were almost never afforded the good educations given to some of their brothers. They were given sufficient education to teach them to manage their households well, perhaps to play musical instruments and produce praiseworthy needlework, to develop conversational skills, but beyond that, even Southern women in the upper echelons of society did not receive the kind of education that their brothers and fathers got. A case in point is Mary and Rebecca Calhoun’s brother John Ewing Colhoun, who was sent off to the College of New Jersey (later Princeton), graduating from there in 1774 before launching a law practice in Charleston and going on to become a U.S. senator. None of the daughters in Ezekiel Calhoun’s family was given the kind of education provided to their brother John.

From a 4 February 1797 letter that John Ewing Colhoun, at that time a Charleston lawyer and planter soon to become a U.S. senator, wrote to William Waddle at Twelve Mile in Pendleton District, we can certainly gather that John relied on his sister’s acumen and good management. He was writing Waddle from St. Johns Island in the lowcountry. His letter instructed Waddle to plant a large kitchen garden at John’s Keowee Heights plantation prior to a trip John was intending to make there, and tells Waddle that if doesn’t have enough seed on the plantation, Mrs. Rebecca Pickens can find more for him.[25]

The preceding is the sum total of what I currently know about Rebecca Calhoun, daughter of Ezekiel Calhoun and Jean Ewing — that is, about what I can document about Rebecca, and, as my comments above indicate, some of the information I’ve shared about her found in published accounts seems to me to lack first-hand sources of documentation. About Rebecca’s famous husband Andrew Pickens, who was a Revolutionary general, there’s much more to say, but since his life is well-covered in a large number of histories and biographies, I won’t write much about Andrew here, though, if I follow the Pickens line back in time on this blog at some point in the future, I may do more with Andrew’s story. Here are some salient pieces of information about Andrew Pickens:

Andrew Pickens

1. I’ve cited above a letter Andrew Pickens sent General Henry Lee on 28 August 1811 in which he states his date and place of birth and provides details about his life prior to his family’s move from Augusta County, Virginia, to the Waxhaws settlement in 1752 or 1753. In the letter, Andrew states that he was born in Paxton (the name was previously Paxtang) township on 19 September 1739. Paxtang was a township in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. I’ve also noted that the same letter says that Andrew’s parents Andrew Pickens Sr. and Ann/Nancy Davis, neither of whom is named in the letter, came from Ireland to Pennsylvania. I also noted that the movements of the family closely parallel those of the Calhoun family, which came to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, from Ireland in 1733, moved to Augusta County, Virginia, by October 1745, and then settled on the Long Cane in South Carolina in February 1756.

2. Andrew Pickens had land in the Long Cane settlement by 2 December 1762, when Patrick Calhoun surveyed a plat of 250 acres for him on Long Cane Creek in Granville (later Abbeville) County.[26] Andrew’s widowed mother Ann Pickens had a survey on the Long Cane on 14 December 1762, when Patrick Calhoun made a plat for 300 acres for her on Norris Creek of the Long Cane, a creek named for the Norris family into which Rebecca Calhoun’s mother Jean Ewing Calhoun married following Ezekiel Calhoun’s death.[27]

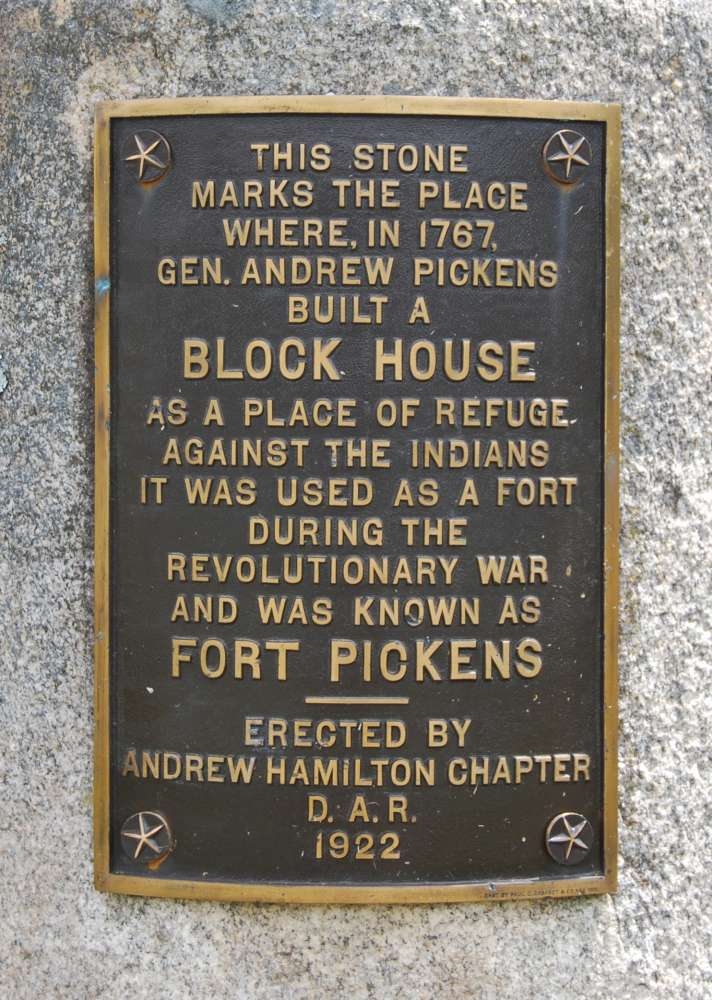

3. As I noted previously, in a letter he wrote on 26 March 1848 to Charles H. Allen, Andrew and Rebecca Calhoun Pickens’ grandson Francis Wilkinson Pickens provides details of his grandfather’s life in the Long Cane settlement prior to the Pickens’ move to Pendleton District. The letter states that Andrew settled in the Long Cane in 1764 — so it appears he was acquiring land in the area prior to his removal there two years later — and in 1765, Andrew settled at the site of the Block House near Abbeville courthouse. Francis W. Pickens tells Charles H. Allen that Andrew Pickens built the Block House in 1767 or 1768 as a place to which local settlers could flee in the event of danger: it was, in other words, a fort. And the letter goes on to say that Andrew Pickens “owned all the lands about the place where the present village [i.e., Abbeville] stands” until he sold them to Major Hamilton.

Andrew Pickens’ Block House is now called Fort Pickens, a name given to it following Andrew Pickens’ death. Markers in the town of Abbeville point to the site on which it stood.[28]

4. Francis Wilkinson Pickens’ 1848 letter also states that at the time his grandfather Andrew Pickens built the Block House, the area in which the fort was sited was a great resort for the Cherokees, who brought to it ginseng, pink root, deer, and bear skins for trade. The letter notes that Andrew Pickens owned a warehouse opposite Augusta to which he sent items he obtained through trade from the Indians, and he also sent droves of beeves to Philadelphia from Abbeville, continuing this business after he moved from Abbeville to Pendleton District. And the letter adds that during the Revolution, Andrew Pickens’ house near the Block House was burnt down by Tories, and his family took refuge in the woods for some weeks, with enslaved people feeding them.

5. There’s abundant material in various published histories and biographies of Andrew Pickens about his illustrious service during the Revolution. Since that’s readily available to researchers, I won’t belabor this part of Andrew’s life, except to note that he served at Ninety-Six in 1775 and at Kettle Creek in Georgia, where the Americans prevailed over the Loyalists, and he played a key role in the American victory at Cowpens in 1781. In recognition of that role, he was made a brigadier-general. He then led his troops at the second “battle” of Ninety Six in 1781 and the recapture of Augusta in the same year. Prior to the Revolution, he had been involved in military actions against the Cherokees, and he played a leading role during the Revolution in defeating the Cherokees, who were British allies.

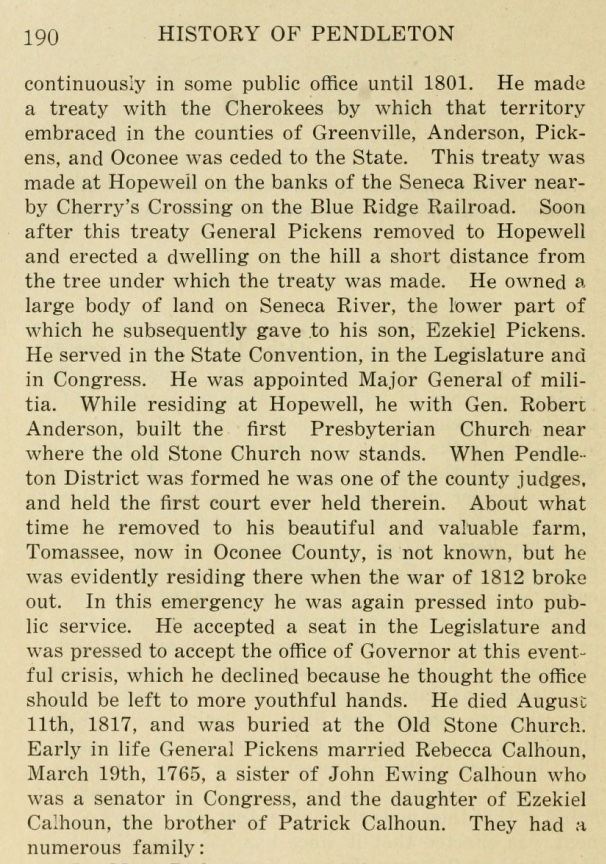

6. Andrew Pickens had a distinguished career as a public servant, which included representing Ninety Six District (later Abbeville County) in the state House of Representatives from 1776 to 1788, and Pendleton District in the state Senate from 1790 to 1793. From 1793-5, he served in the U.S. House of Representatives, and subsequently returned to the South Carolina legislature to represent Pendleton District from 1796-9. In 1812, he came out of retirement to serve a final term in the South Carolina General Assembly, declining a nomination to run for governor in that year.

7. One of Andrew Pickens’ noted activities, particularly in the post-Revolutionary period, was his negotiation with (and some historians might say, pressuring of) the Cherokees and other native peoples to the west regarding the lands they held. Even before the Revolution, he had taken part in forays against the Cherokees from the South Carolina upcountry, and those continued during the Revolution. Following the Revolution, he acted as the commissioner who brought about the most important treaties that opened to white settlement land previously occupied by the Cherokees, Creeks, Choctaws, and Chickasaws. By his negotiations, South Carolina got total right to all the Cherokee lands that now comprise much of Greenville, Anderson, Oconee, and Pickens Counties. The treaties named Hopewell, Natchez, and Milledgeville brought the remainder of the territory east of the Mississippi and south of the Ohio into United States territory. Andrew Pickens was one of the chief operatives in the settling of state boundary disputes among South Carolina, Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee.[29]

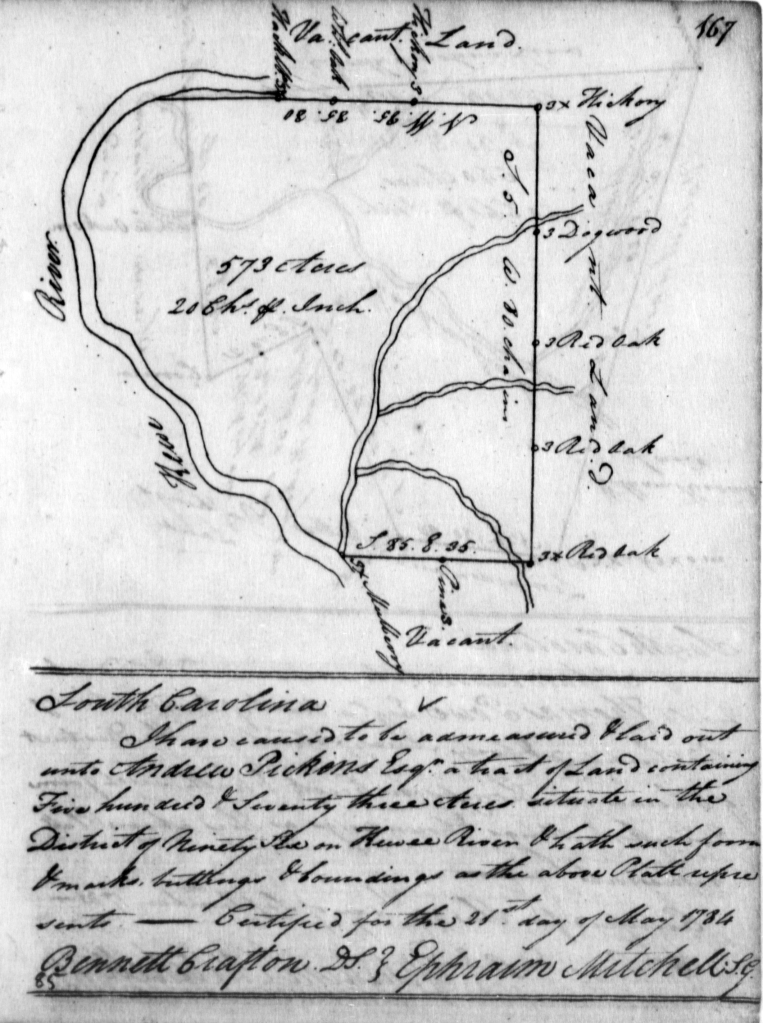

8. On 16 July 1784, Andrew Pickens bought 573 acres on the Keowee River in Pendleton District, where his brother-in-law John Ewing Colhoun also acquired land in 1784 for what became his Keowee Heights plantation.[30] As a previous posting notes, John E. Colhoun’s sister (and Andrew Pickens’ sister-in-law) Mary Calhoun Kerr also bought land in Pendleton District in 1784. By 1785, Andrew Pickens had built a house overlooking the Keowee on this 573-acre tract of land, but the family did not move into the house until the summer of 1786. It was given the name Hopewell after the church in the Long Cane settlement founded by Rebecca Calhoun Pickens’ brother Patrick, which the Pickens family attended.[31] Hopewell was a two-story structure made from hand-hewn logs overlaid with weather-boarding, with a porch across the front, with wide halls and two large rooms on either side. It is now on the land of Clemson University overlooking the lake.[32] The Hopewell house was some three miles from Pendleton courthouse. As Francis Wilkinson Pickens’ March 1848 letter to Charles H. Allen states, following his move from the Long Cane to Pendleton District, Andrew Pickens and Colonel (Benjamin) Cleveland of Greenville constituted a court, hearing all cases tried in the area for several years.

9. According to Beth Ann Klossky, when the family of Andrew Pickens and Rebecca Calhoun relocated from their home in the Long Cane settlement to their Pendleton District land on the Keowee in 1786, they probably initially attended the Twenty-Three Mile or Richmond-Carmel Presbyterian church on the plantation of Andrew’s uncle Robert in Pendleton District.[33] On 13 October 1789, Andrew, along with Colonel Robert Anderson and other neighbors, petitioned the Presbyterian Synod for supplies for Richmond and Hopewell churches, the latter named for Andrew Pickens’ former church in the Long Cane settlement, and the Hopewell Presbyterian Society was then established in Pendleton District.[34]

At this point, no building had yet been built for the Hopewell church. In 1790, a log church was constructed near the home of Andrew Pickens’ son Ezekiel in the vicinity of present-day Clemson. This church burned in 1796, and its ruins can still be seen at the edge of Clemson University’s South Experimental Forest.[35]

In 1797, construction began on a new Hopewell church, with Irish stonemason John Rush supervising this project and doing much of the stonework, and the building was completed about 1800. This the structure now known as the Old Stone Church in whose cemetery Andrew Pickens and wife Rebecca Calhoun are buried. Subscribers contributing to the construction of the stone church included Andrew Pickens, his neighbor and friend Robert Anderson, and his brother-in-law John Ewing Colhoun.[36]

Beth Ann Klossky indicates that an academy, Hopewell Academy, was established at the Old Stone Church from as early as 1800, with Robert Anderson and Andrew Pickens on its board of trustees.[37] This was a classical academy and one of the earliest such educational institutions in the upcountry. According to Klossky, when a frame church was built in Pendleton village in 1824, the Old Stone Church was abandoned, with the name Hopewell then falling into disuse and the new church being known as Pendleton Presbyterian church.[38]

For a photographic essay about Old Stone Church and its cemetery, please see this posting with photos I took there on 4 May 2024.

In the spring of 1805, Andrew and Rebecca Calhoun Pickens moved from their Hopewell house on the Keowee to land Andrew had acquired on Tamassee Creek north of Hopewell in what became Pickens County in 1826 and then Oconee County in 1868. When Andrew and Rebecca made this move, they gave the Hopewell house to their sons Ezekiel and Andrew, with Andrew living in the house until he moved to Alabama in the early 1820s. The Pendleton District Historical and Recreational Commission’s Pendleton Historic District: A Survey, cites an 1806 diary entry written by Edward Hooker when he visited Andrew Pickens younger at the Hopewell house, in which Hooker noted,[39]

They live in the old family mansion — the General his father having removed to a farm (Tamassee) at the foot of the mountains 15 or 20 miles distant.

On their Tamassee farm, Andrew Pickens and wife Rebecca lived in a house called Red House that is no longer standing. It was there that Andrew died on 11 August 1817, having been predeceased by wife Rebecca, who died at their farm on Tamassee Creek on 19 December 1814. As has previously been stated, Andrew Pickens and wife Rebecca Calhoun are buried together in the cemetery of the Old Stone Church at Clemson in Pickens County, South Carolina, a county named for him. The inscription on Andrew Pickens’ tombstone reads,

Genl. ANDREW PICKENS was born 13th. September 1739, and died 11th. August 1817. He was a Christian a Patriot, & Soldier. His Character & actions are incorporated with the history of his Country. Filial affection & respect raise this stone to his memory.

In his History of Old Pendleton District, Richard Wright Simpson provides a biography of Andrew Pickens that Simpson says was drawn from an obituary published in Pendleton Messenger on 27 August 1817 following Andrew Pickens’ death on 11 August.[40] The biography is above. It’s not clear to me whether this is a verbatim transcript of the obituary cited by Richard Simpson or whether the Simpson biography summarizes the obituary while adding more material to it.

[1] Margaret Ewing Fife, Ewing in Early America, part 1 (Fife, Atlanta, 1995), pp. 141f.

[2] South Carolina Will Bk. 1760-7, pp. 181-2.

[3] See Find a Grave memorial page of Rebecca Calhoun Pickens, Old Stone Church cemetery, Clemson, Pickens County, South Carolina, created by Jimmy Gilstrap, maintained by C. LATTA, with a tombstone photo by photo by Scott F. Lewis.

[4] The portrait in question is found in William Montgomery Meigs, The Life of John Caldwell Calhoun, vol. 2 (New York: Neale, 1917), p. 80, where it’s clearly labeled as a miniature of Mrs. John C. Calhoun. See also Find a Grave memorial page of Floride Bonneau Calhoun, created by The Perplexed Historian, maintained by Find a Grave; and “Floride Calhoun” at Wikipedia.

[5] On the F.W. Pickens Papers, see “F. W. Pickens papers, 1798-1900, bulk 1809-1886,” at the website of Duke University’s David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

[6] In addition to the two white marble markers at their gravesites, the graves of Andrew and his wife Rebecca have faux-crypt tombstones (flat markers placed on top of raised brick rectangles).

[7] Bobby F. Edmonds, The Making of McCormick County (McCormick, South Carolina: Cedar Hill, 1999), p. 19.

[8] William R. Reynolds, Andrew Pickens: South Carolina Patriot in the Revolutionary War (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2012), pp. 20-1. Brian Scott, The Long Cane Massacre (priv. publ., Lulu, 2017), p. 33, also has the story of Rebecca Calhoun hiding during the massacre and escaping death due to this.

[9] Bobby Edmonds cites Alice Noble Waring, The Fighting Elder: Andrew Pickens (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1962), pp. 3-5. Waring cites Henry Alexander White, The Making of South Carolina (New York: Silver, Burdett, 1906), p. 63; Edward McCrady, The History of South Carolina under the Royal Government, 1719-1776, vol. 2 (New York: Macmillan, 1899), pp. 295-326, 342-3; and A.S. Salley Jr., “The Calhoun Family of South Carolina,” South Carolina History and Genealogy 7,2 (April 1906), p. 85. But none of these sources, including Waring herself, recount this story of Rebecca Calhoun hiding during the massacre and being found by her uncle a day later. I also do not find a clear source for this story in the sources Reynolds cites.

[10] “The Long Cane Massacre — Newspaper Reports,” at the Long Cane Webpage site.

[11] John H. Logan transcribes this letter in A History of the Upper Country of South Carolina, vol. 2 (Charleston: Courtenay, 1859), pp. 94-7.

[12] See e.g., Reynolds, Andrew Pickens, p. 26; W.A. Courtenay, “Andrew Pickens,” in Old Stone Church and Cemetery Association, with Andrew Pickens and Cateechee Chapters of DAR, The Old Stone Church—Oconee County —South Carolina, ed. Richard Newman Brackett (Columbia: Ryan, 1905), pp. 138-9, which was evidently previously published in Cowpens Centennial; A.L. Pickens, Skyagunsta, the Border Wizard Owl (Greenville, South Carolina: Observer, 1934), p. 4; James Henry Rice, “Andrew Pickens,” American Monthly Magazine 7,1 (July 1895), pp. 28-29; Mrs. S. Bleckley, “Rebecca Calhoun Pickens,” American Monthly Magazine 37,3 (September 1910), p. 216; Harry Clinton Green and Mary Wolcott Green, The Pioneer Mothers of America: A Record of the More Notable Women of the Early Days of the Country, and Particularly of the Colonial and Revolutionary Periods (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1912), pp. 181-184; Elizabeth F. Ellet, The Women of the American Revolution, vol. 3 (New York: Baker and Scribner, 1848) pp. 303-4; and Monroe Pickens, Cousin Monroe’s History of the Pickens Family (Easley, South Carolina: Day, 1951), pp. 40-1.

[13] The original letter is in the Thomas Sumter Papers, 1763-1885, of the Lyman Draper Manuscript Collection held by Wisconsin Historical Society—series VV, volume 1.

[14] On Picken/s as a Scottish surname found notably in Ayrshire, see George F. Black, The Surnames of Scotland: Their Origin, Meaning, and History (New York: New York Public Library, 1946), p. 661.

[15] The journal of William Calhoun is transcribed in A.S. Salley, “Journal of William Calhoun,” Publications of Southern Historical Association 8,3 (May 1904), pp. 179-195. The marriage of Andrew and Rebecca, as noted in William Calhoun’s journal, is on p. 192 of this transcription.

[16] See supra, n. 12.

[17] Rice, “Andrew Pickens,” pp. 28-9.

[18] Bleckley, “Rebecca Calhoun Pickens,” p. 216; Monroe Pickens, Cousin Monroe’s History of the Pickens Family, pp. 40-1.

[19] Bleckley, “Rebecca Calhoun Pickens,” pp. 216-7.

[20] Ibid., p. 218.

[21] Ibid., p. 218.

[22] Lewin Dwinnell McPherson, Calhoun, Hamilton, Baskin, and Related Families (1957), p. 51.

[23] On the “abysmal” literacy rates of women in the colonial South, and the gendering of education so that only high-status males were educated and women were kept in subordinate status by lack of education, see Catherine Kerrison, “By the Book: How Novels Filled Intellectual Voids in the Lives of Colonial Women Trend & Tradition,” Trend and Tradition 2,2 (Spring 2017), pp. 80-1.

[24] See Margo Todd, The Culture of Protestantism in Early Modern Scotland (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002), pp. 63-4.

[25] The letter is in the John Ewing Colhoun Papers of the Southern Historical Collection held by Wilson Library at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

[26] South Carolina Colonial Plat Bk. 7, p. 369.

[27] Ibid., Bk. 9, p. 244.

[28] See Brian Scott, “Colonial Block House/Fort Pickens,” and “Fort Pickens,” at the Historical Marker Database website.

[29] I want to acknowledge for this paragraph the work of Richard W. Fowler in his book Connections, a Genealogical Encyclopedia of 50,000 Individuals Related and Connected to Pioneer Families of Upstate South Carolina (priv. publ., Inman, South Carolina, 2000). In May 2000, Richard Fowler sent me a condensed version of the section of the book dealing with Andrew Pickens and Rebecca Calhoun.

[30] Pendleton District Historical and Recreational Commission, Pendleton Historic District: A Survey (Pendleton, South Carolina: Pendleton District Historical and Recreational Commission, 1973), p. 20.

[31] Photos of the Hopewell house taken in about 1930 and in 1976 are in ibid., p. 21.

[32] See “Hopewell Plantation: Pickens Family Plantation & Treaty Site,” at the Clemson University website.

[33] Beth Ann Klossky, The Pendleton Legacy,(Columbia: Sandlapper, 1971), p. 23.

[34] Ibid., p. 24.

[35] Ibid., pp. 25-6; and Pendleton Historic District: A Survey, pp. 13-4.

[36] Klossky, The Pendleton Legacy, p. 26; and Pendleton Historic District: A Survey, pp. 13-4, 63.

[37] Klossky, The Pendleton Legacy, p. 26.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Pendleton Historic District: A Survey, p. 20.

[40] Richard Wright Simpson, History of Old Pendleton District, with a Genealogy of the Leading Families of the District (Anderson, South Carolina: Oulla, 1913), pp. 189-197.

5 thoughts on “Children of Ezekiel Calhoun and Jean/Jane Ewing: Rebecca Calhoun (1745-1814) and Husband Andrew Pickens”