The Pennsylvania Years, 1733-1744/1745

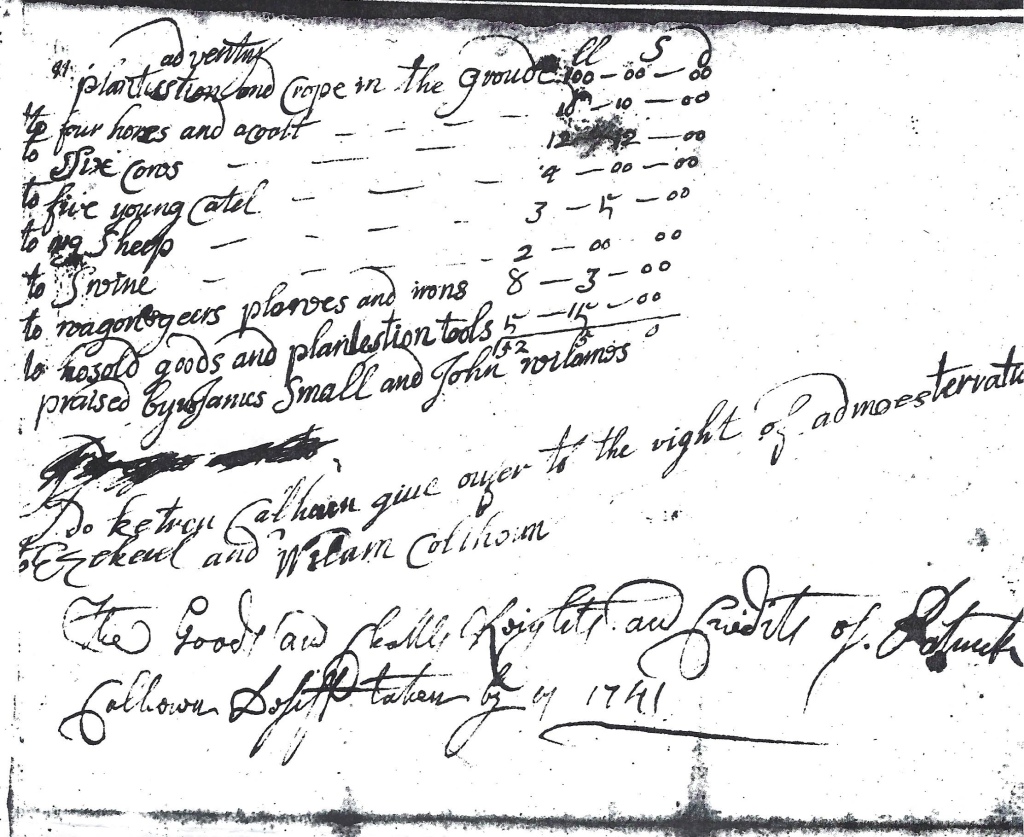

In her Early Adventurers on the Western Waters, Mary B. Kegley provides a brief biography of Ezekiel Calhoun which notes that he was born about 1720 in Ireland, married Jean Ewing,[1] and had children John Ewing, Patrick, Ezekiel, Mary, and Rebecca.[2] Kegley notes that the Calhoun family, headed by Patrick Calhoun and wife Catherine Montgomery, is said to have come to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, from County Donegal, Ireland, in 1733.[3] Patrick Calhoun died in Lancaster County in 1740 or 1741, and when his estate was inventoried at an unspecified date in 1741, his widow Catherine relinquished administration of the estate to her sons Ezekiel and William,[4] writing,

I do ketren Calhoun give over to the right of admoesternate to Ezekewl and Wilam Colihoun.

And underneath what Catherine has written someone writing in a different hand states that this document is an inventory of Patrick Calhoun’s goods and chattel.

On 4 May 1743, Ezekiel and William Calhoun gave bond in Lancaster County with their brother-in-law John Noble (married Mary Calhoun) and James Mitchell for administration of Patrick Calhoun’s estate, and the estate was settled by 4 May 1744 (see the image at the head of the posting).[5] By October 1745, Catherine Montgomery Calhoun had moved with her sons James, Ezekiel, William, and Patrick and her daughter Mary with husband John Noble to Augusta (later Wythe) County, Virginia. As Kegley notes, the Calhouns were in Augusta County by 18 October 1745 when James Patton entered land there for Colonel John Buchanan, stating that one of Buchanan’s chosen tracts was on Reed Creek “about fifteen miles above Calhouns.”[6]

The Move to Reed Creek in Augusta County, Virginia, by October 1745

Prior to the Calhoun family’s move from Pennsylvania to Virginia, Ezekiel Calhoun had married Jane/Jean Ewing about 1742. As a previous posting notes, Ezekiel and Jane’s oldest child Mary, my ancestor, appears to have been born about 1743 prior to the family’s move to Virginia. Ewing researcher Margaret Fife has concluded that Jane/Jean Ewing was likely a daughter of Patrick and Mary Ewing of Drumore (later Little Britain) township in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, who appear to have come to Pennsylvania from Elaghbeg in Burt Parish, County Donegal, Ireland.[7] Patrick Ewing died in Little Britain township, Lancaster County, after 15 March 1738/9. Margaret Fife thinks that Ezekiel Calhoun and Jane/Jean Ewing married in 1743 or 1744, perhaps at Chestnut Level in Lancaster County.[8]

As Kegley notes, as some of the earliest settlers of the Reed Creek area of what became Wythe County, the Calhouns had “their choice of the finest land on Reed Creek, and their selections are still so regarded today.”[9] Kegley adds,

At the time of their settlement, the Woods River Company under the direction of Colonel James Patton was seeking out families to settle on the large grant which had been obtained by the company in 1745. For a variety of reasons the early adventurers often were living on the land they had selected without actual title to the land, but the company eventually found a surveyor to lay off the ground and after a year or more the land grant would be issued.

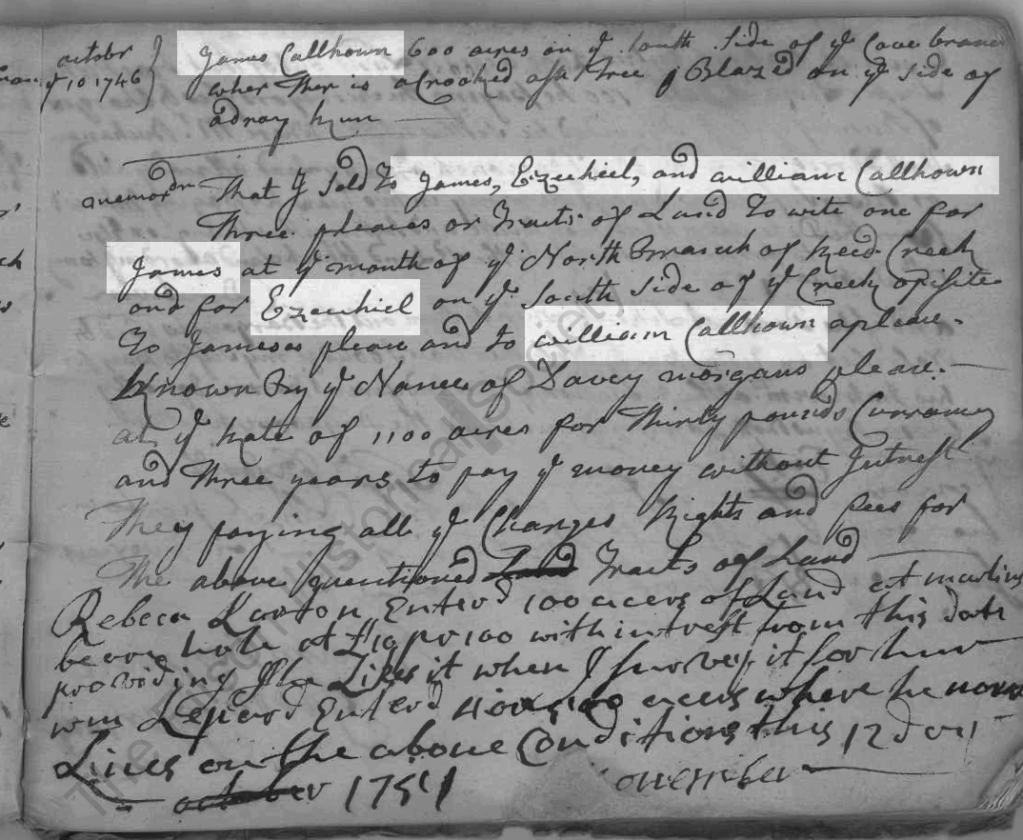

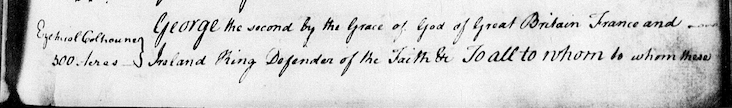

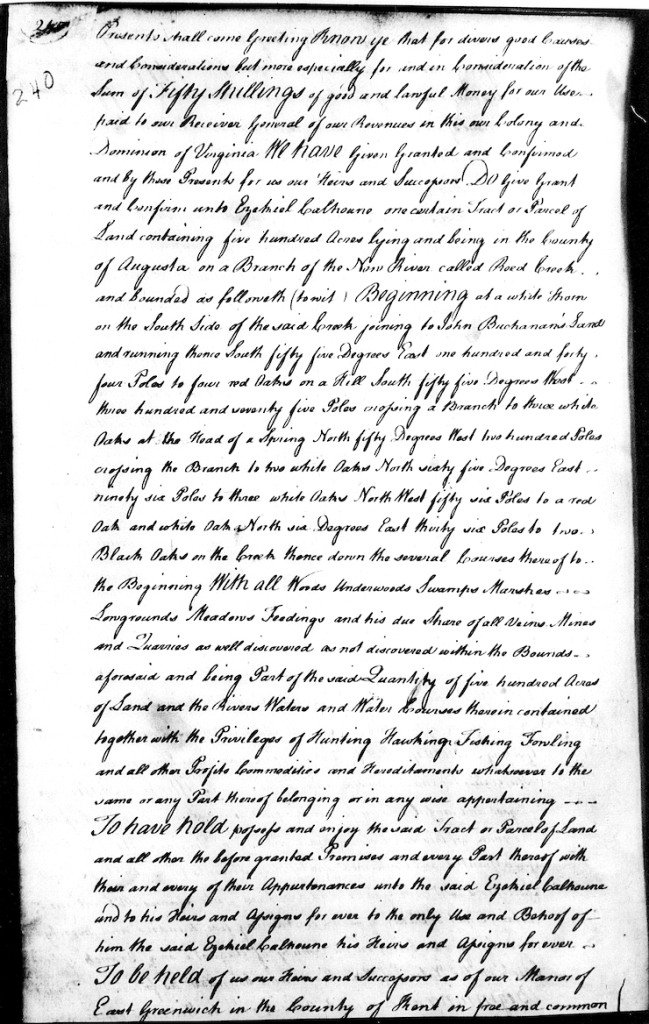

On 10 October 1746, James Patton’s Woods River entry book shows brothers James, Ezekiel, and William Calhoun each paying for tracts of land, with James’ and Ezekiel’s tracts both sited on Reed Creek across from each other, James on the north side and Ezekiel on the south side.[10] The grant for Ezekiel’s tract, which was made by Virginia lieutenant-governor Robert Dinwiddie on 1 October 1752, shows that it was 500 acres on Reed Creek, which the grant notes was a branch of New River.[11]

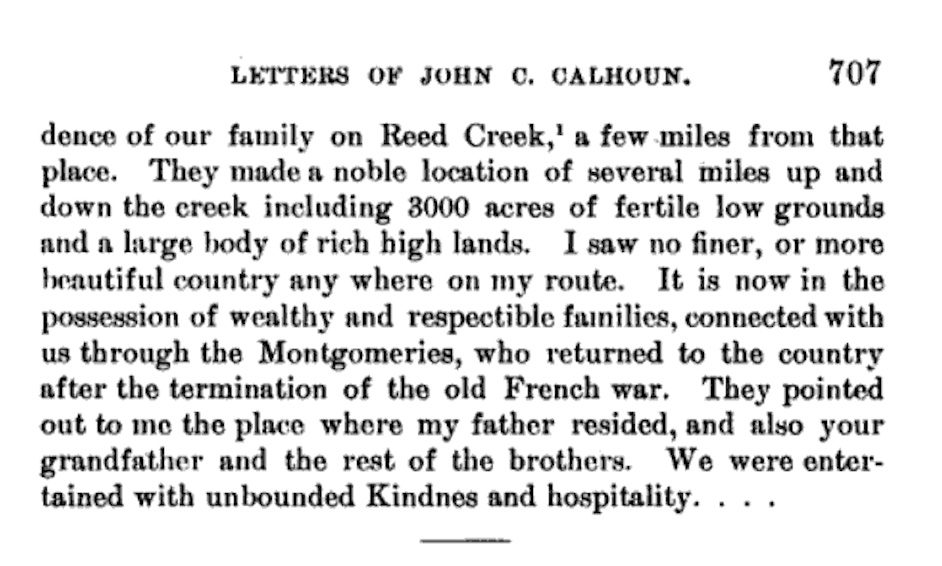

Kegley’s bicentennial history of Wythe County has a photo taken by Arthur M. Kent of Ezekiel Calhoun’s land on Reed Creek.[12] Kegley notes that the land was excellent, and later belonged to Joseph Kent and then to George W. Simmerman, from whom it passed to B.C. Umberger in 1984.

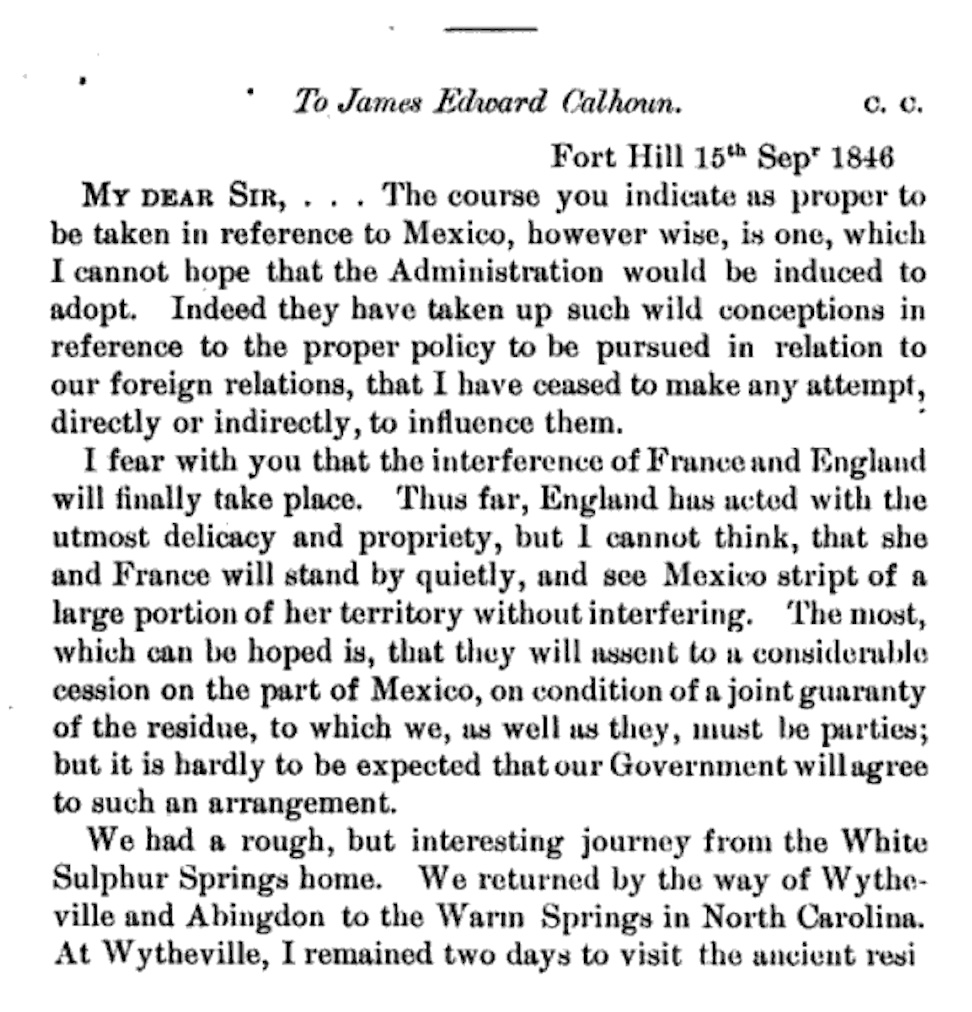

In a letter he wrote to Ezekiel’s grandson James Edward Calhoun, son of John Ewing Colhoun, on 15 September 1846, John C. Calhoun, who was Ezekiel’s nephew (son of Patrick Calhoun), wrote that he had recently journeyed from White Sulphur Springs in Greenbrier County, Virginia (now West Virginia), through Wytheville and Abingdon, Virginia, to Warm Springs in North Carolina.[13] John C. Calhoun was writing from Fort Hill, South Carolina. James Edward Calhoun was not only John C. Calhoun’s cousin but also his brother-in-law: John C. Calhoun married James Edward’s sister Floride Bonneau Colhoun. About the visit to Wytheville, John C. Calhoun tells James Edward,

At Wytheville, I remained two days to visit the ancient residence of our family on Reed Creek, a few miles from that place. They made a noble location of several miles up and down the Creek including 3000 acres of fertile low grounds and a large body of rich high lands. I saw no finer, or more beautiful country any where on my route. It is now in the possession of wealthy and respectible [sic] families, connected with us through the Montgomeries, who returned to the country after the termination of the old French war. They pointed out to me the place where my father resided, and also your grandfather and the rest of the brothers. We were entertained with unbounded Kindnes and hospitality….

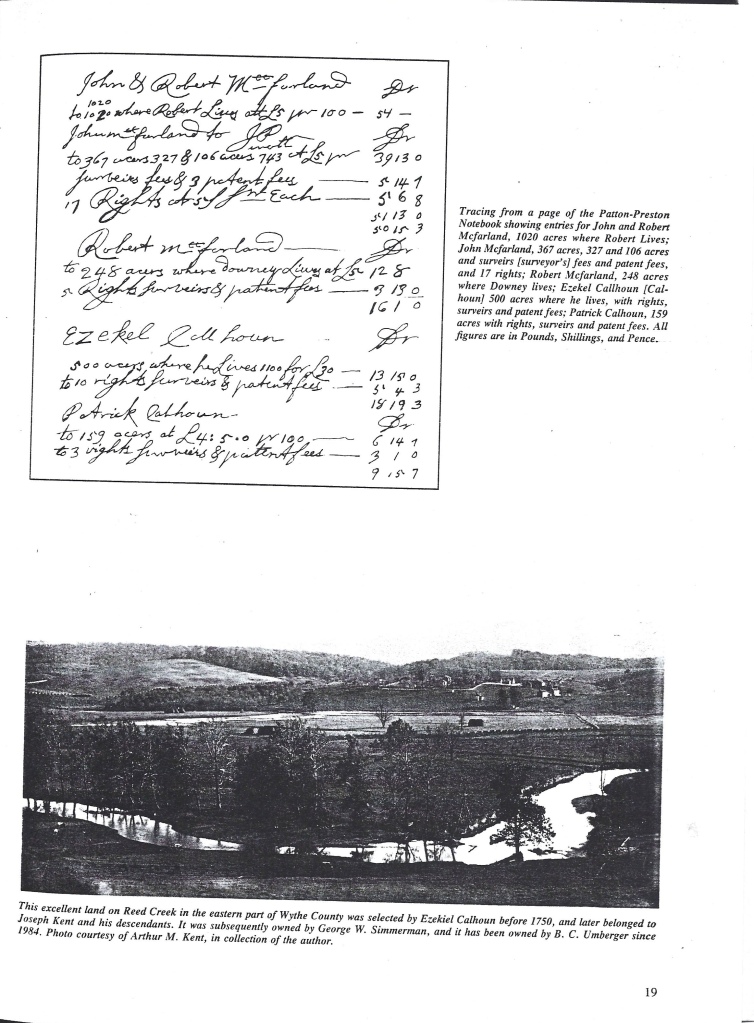

Mary Kegley’s previously cited bicentennial history of Wythe County offers a tracing from a page of the Patton-Preston Notebook (see the image above) which shows an undated entry in the notebook listing Ezekiel Calhoun’s 500 acres, on which he was living when the entry was made, and noting his payment of £18 19s 3d for the land, surveys, and patent fees.[14]

Despite his having sold Woods River Company land to them, James Patton became crosswise with the Calhoun brothers soon after they settled in Virginia. Court minutes for Augusta County court note on 19 September 1746 that Patton had filed suit against James, Ezekiel, William, and Patrick Calhoun, charging them with being “divulgers of false news to the detriment of the Inhabitants of the colony.”[15] The brothers were ordered to appear at November court to answer Patton’s complaint.

Noting that “[t]he Calhoun land was not taken up without disputes and apparently they were of extraordinary proportions,” Mary B. Kegley offers valuable commentary about what were points of contention between Patton and the Calhoun brothers.[16] Having sold Woods River land to the Calhouns, Patton apparently challenged their title to the specific tracts they had selected, and charged the Calhouns with slander when, as he claimed, James Calhoun stated that Patton had no title to the lands he was selling and had made over his estate to his children to defraud his creditors.

Kegley points to a 16 May 1750 document found in the Preston Papers held by the Library of Congress, which shows that on 3 November 1748, a dispute had arisen between the Calhouns and Patton over land boundaries, which John Madison and John Wilson adjudicated on 16 May 1750. At issue was the precise location of tracts that had been sold to James and Patrick Calhoun, their brother-in-law John Noble, and their kinsman John Montgomery.[17] John Noble’s claims were voided by judicial decision.

A slander suit Patton brought against James Calhoun in 1754 shows him claiming that in 1750, Calhoun had made the allegations about him noted above; the suit suggests that the charges of slander Patton was making against the Calhouns as early as September 1746 were rooted in disputes over land boundaries. The 1754 slander suit also indicates that the Calhouns accused Patton of tacking patent fees onto their land claims and then withholding their title to their tracts of land when they objected to these fees.[18] Due to his disputes with the Calhoun brothers, by 1747 Patton was designating the section of the county in which they had settled “the Valley of Contention and Strife,” or the trace “of Pride and Self-Concete.”[19]

In addition to appearing in Augusta County court minutes in September 1746 when Patton charged them with being “divulgers of false news,” Ezekiel Calhoun and his brothers William and Patrick are mentioned in court minutes on 19 November 1746, when they were appointed to work the road from Reed Creek to Eagle Bottom and to the top of the ridge parting the waters of New River and the south fork of Roanoke, with brother James overseeing the road work.[20]

Kegley also notes that in 1750, court order books show that a road was built from Ezekiel Calhoun’s on Reed Creek to the New River.[21] Kegley says that the road continued on high ground north of present state highway 11 and interstate highway 81. A.S. Salley indicates that this court order was given on 23 May 1750.[22]

On 24 January 1755 when Robert Ewing and wife Mary (Baker) of Lunenburg County, Virginia, sold Benjamin Starret of Augusta County 160 acres in Augusta, witnesses to the deed included James, Patrick, and Hugh Calhoun.[23] James and Patrick were, of course, Calhoun brothers; Hugh is a Calhoun who shows up in both Augusta County records and those of the Long Cane settlement in South Carolina in connection with the Calhoun brothers, and is thought to have been their relative, though the exact relationship has not, to my knowledge, been determined. Patrick and James Calhoun proved this deed in Augusta County on 21 August 1755.

Margaret Fife places Robert Ewing in the Ewing family from which Ezekiel Calhoun’s wife Jane/Jean Ewing descends.[24] She concludes that he was the brother of a James Ewing who was born in Ireland about 1712 and who died about 1788 in Prince Edward County, Virginia, in whose records he appears after that county was formed in 1753/4 from Amelia County, where James was previously found. Fife notes that Robert Gillespie, who married Frances Ewing and who also went to Amelia and Prince Edward Counties, was Ezekiel Calhoun’s brother-in-law.[25] Robert is named as the son-in-law of Mary Ewing, mother of Jane/Jean Ewing Calhoun (as Fife thinks), in Mary’s Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, will in February 1741/2.[26] According to Fife, Robert Gillespie moved with wife Frances and members of her Ewing family from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, to Cecil County, Maryland, in the early 1740s, and from there to Amelia County, Virginia, by May 1744.[27]

The Move to the Long Cane Region (Later Abbeville County) of South Carolina in 1755

As a previous posting has noted, following General Edward Braddock’s defeat by the French in the Battle of the Monongahela on 9 July 1755, the Calhoun family left Augusta County, Virginia, for South Carolina. The linked posting quotes (and reproduces a transcription of) a letter that John C. Calhoun sent to Charles H. Allen on 21 November 1847 in which Calhoun states,[28]

Our family were driven from the back part of Virginia in consequence of Braddock’s Defeat in the old French war.

In the same letter, John C. Calhoun tells Charles Allen that his father Patrick Calhoun had kept a journal recounting the circumstances of the family’s emigration from Wythe County, Virginia, and that he had read this journal before he went to college and had left it in a desk, but by the time he returned home from college, the journal had disappeared and he feared it was lost forever. The letter states,

My father (Patk. Calhoun) with his three brothers and his sister and her husband arrived in the District (Abbeville) February, 1756, & settled in a group in what is now known as Calhoun’s Settlement, at the fork of the two streams of that name.

Note that in saying the Calhouns left Wythe County, John C. Calhoun was using the name for the county from 1790 forward, when Wythe was formed from Montgomery County (which was cut out from Fincastle, of which Botetourt was the parent county, with Botetourt being formed from Augusta in 1770). Unless I’m mistaken, John Noble, husband of John C. Calhoun’s aunt Mary Calhoun Noble, had also died prior to the exodus of these families from Augusta County, Virginia, with a will dated 10 June 1752 and probated 16 November 1752. John C. Calhoun’s letter also omits to note that his grandmother Catherine Montgomery Calhoun moved with her sons and daughter to South Carolina, and would then be killed in the Long Cane massacre on 1 February 1760.

As the posting linked above also indicates, McCormick County, South Carolina, historian Bobby Edmonds states that when the Calhoun family left Virginia following Braddock’s defeat, the family followed the Great Wagon Road down to the Waxhaws on the border of the two Carolinas, and were then convinced by a band of hunters to visit the Long Cane area in South Carolina, to which they relocated in February 1756.[29]

About the Calhouns’ relocation from Virginia to South Carolina, Mary B. Kegley says only,[30]

All of the family moved to South Carolina in 1756 following Indian troubles on the Virginia frontier.

In his history of South Carolina, David Ramsay indicates that the defeat of Braddock in 1755 exposed the frontiers of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia to danger, spurring an exodus of those who had settled in these areas southward.[31] Ramsay notes that the Calhoun family took part in this exodus as they moved to the Long Cane region of what was then Granville County and would become Abbeville County, and were among the first settlers of that region.

Citing the letter of John C. Calhoun to Charles H. Allen, A.S. Salley says that James, Ezekiel, William, and Patrick Calhoun moved with their sister Mary Noble and mother Catherine Calhoun from Virginia to South Carolina in 1756, arriving in South Carolina in February 1756.[32] In an account he composed tracking the Calhouns’ move to South Carolina, researcher Leonardo Andrea notes that Salley has the Calhouns moving directly from Virginia to South Carolina, but concludes that the Calhouns first settled in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, in the Waxhaws vicinity, before heading to South Carolina.[33] For this information, Andrea cites Logan, McCrady, and “other South Carolina historians.”[34]

In his history of South Carolina under the royal government, Edward McCrady says that the Scotch-Irish families who settled in the Waxhaws in the 1740s and 1750s included the Jacksons, Calhouns, and Pickens.[35] According to McCrady, Patrick Calhoun, father of John C. Calhoun, first settled (presumably with his brothers, sister, and mother) at the Waxhaws before going to what became Abbeville County, returning to the Waxhaws following the Long Cane Massacre and marrying his first wife Jane/Jean Craighead there. McCrady also notes that it was at the Waxhaws that Ezekiel Calhoun’s daughter Rebecca met Andrew Pickens, whom she married, but as Andrew and Rebecca’s grandson Francis Wilkinson Pickens states in a 26 March 1848 letter he wrote to Charles H. Allen, this occurred after the Calhouns had settled on the Long Cane in February 1756.[36] The letter says that following the Long Cane massacre in February 1760, Ezekiel Calhoun took his family to the Waxhaws for safety, and this is when Andrew Pickens and Ezekiel’s daughter Rebecca met.

I’m not sure what to think about the discrepancy between reports that the Calhouns traveled immediately from Augusta County, Virginia, to the Long Cane region of South Carolina, and reports that the family first sojourned in the Waxhaws before settling on the Long Cane. It’s clear to me that some family members did leave the Long Cane area to go to the Waxhaws after the Long Cane massacre in 1760, and then returned to the Long Cane when it seemed safe to do so. So I wonder if memories of those events have somehow been retrojected into accounts that they settled in the Waxhaw settlement before going to the Long Cane.

If it’s true that, as Bobby Edmonds reports, the Calhouns took the Great Wagon Road from southwestern Virginia into the Carolinas, then it would have made sense for them to stop in the Waxhaws, since a branch of that road went through the Waxhaws. On the other hand, if they left Virginia due to Braddock’s defeat in July 1755, as John C. Calhoun’s letter to Charles H. Allen states, and if they then settled on the Long Cane in February 1756, as the same testimony indicates, they could not have been in the Waxhaws long, given the time it would have taken them to travel from Virginia into the Carolinas and then on to the Long Cane.

The Calhouns Settle on the Long Cane in February 1756

According to Bobby Edmonds, when the Calhouns arrived in the Long Cane region in February 1756, they initially settled east of Long Cane Creek where they built a fort, Fort Long Cane, less than a mile east of Long Cane A.R.P. church and two miles west of present-day Troy, South Carolina.[37] Edmonds says that before 1756 ended, the Calhouns crossed Long Cane Creek and relocated a few miles to the north on Little River near present-day Mt. Carmel.[38] Troy is in Greenwood County, and Mt. Carmel in McCormick County adjoining Greenwood on the west, with Greenwood bordering Abbeville County on the east and south and McCormick bordering Abbeville on the south. Greenwood was formed in 1897 from Abbeville and Edgefield Counties, and McCormick in 1916 from Greenwood, Edgefield, and Abbeville Counties.

As a previous posting indicates, in his November 1847 letter to Charles Allen discussed above, John C. Calhoun states that his uncle William Calhoun settled “in the fork of Calhoun’s Creek and Little River.” This is just north of present-day Mt. Carmel.

Though the Calhouns had come to this region in the hope of avoiding the disturbances with native Americans to the west that ensued in western Virginia following Braddock’s defeat, their settlement on the Long Cane was from the outset, as Lester W. Ferguson states, a thorn in the side of the Cherokees, who saw it as a violation of boundary treaties.[39] This set the stage for the Long Cane massacre in 1760, about which I’ll say more in a moment.

Trouble Ensues with Cherokee Neighbors to the West

John C. Calhoun’s November 1847 letter to Charles H. Allen states that the land on which the Calhouns settled on Long Cane “had been recently got from the Cherokees,” and was more than 16 or 17 miles from the boundary line separating the Cherokees and white settlements. The letter says that the Long Cane land was “in a virgin state, new & beautiful, without underwood & all the fertile portion covered by a dense cane-brake.” John C. Calhoun adds, “The region was full of deer and other game, & among them, the buffalo.”

When John C. Calhoun spoke to Charles H. Allen of the Calhouns having settled in 1756 on land that “had been recently got from the Cherokees,” he was, I think, referring to a land sale Cherokee leaders made to the British crown in February 1747, in which they sold the lands on Long Cane Creek and the Little River drainage areas. South Carolina governor James Glen met with sixty-one Cherokee leaders at Ninety Six on 1 June 1746 to affirm the crown’s intent to maintain peaceful relations with their people as the colony anticipated settlers of European descent to begin populating the backcountry. The Cherokees’ sale of land to the crown in 1747 resulted from that meeting.[40]

The expectation that there would be continued peace with the Cherokees to the west and with settlers of European background arriving in the upcountry spurred land speculation in that part of South Carolina. In 1749, John Hamilton acquired title to 200,000 acres south of Ninety Six with the stipulation that he was to settle 1,000 Protestants on the tract within ten years, and in 1751 he commissioned a survey of his vast tract of land. Unless I’m mistaken, the land on which the Calhouns settled was part of this tract.[41] As historian Robert Meriwether notes,[42]

In November 1751 Surveyor-General George Hunter surveyed the two hundred thousand acres of “Hamilton’s Great Survey” in four plats of equal area. The tract, nearly eighteen miles on a side, extended from the Saluda River far into the valleys of Long Cane and Stevens Creeks, and lay immediately above Thomas Brown’s 1738 plat. The southernmost plat enclosed two surveys already made for John Hamilton amounting to twelve thousand nine hundred acres.

Though some commentators have suggested that the Calhouns settled on Long Cane land that the Cherokees had not sold to the crown, and were therefore squatting on the land, I think that allegation is baseless. As Jessica L. Cook explains, the thorn in the side of the Cherokees was not that the Calhoun settlement was encroaching on Cherokee territory and that the Calhouns did not have legal title to their land: the Cherokees were disturbed by the Long Cane settlement because they understood territoriality differently than the white settlers of the upcountry did, and had not realized that, in selling their land, they were also forfeiting their right to hunt on land they had long used for hunting. She writes,[43]

Cherokee fury over the Long Canes settlers’ choice of land arose not because the settlers trespassed beyond a British line, but because they viewed the settlers’ permanent occupation and alteration of land a violation of their own system for land management.

As Cook also states,[44]

By Cherokee understanding, the 1747 agreement gave the British rights to use the land up to Long Cane Creek, but did not necessarily preclude continued use of the hunting grounds.

Cook explains that the Long Cane land on which the Calhouns settled was land the Cherokees had long used for hunting deer. They had carefully cultivated and groomed it to create areas in the forks of waterways such as the Long Cane Creek into which they could chase deer and make it easier to hunt them. The problem that festered with the Cherokees and with the settlers on the Long Cane was, Cook thinks, caused by the absence of a clearly defined boundary line between the two groups of people. The Cherokees considered the land on which the Calhouns had settled their hunting ground that should still be accessible despite the Calhouns’ legal ownership of it.[45]

In my next posting, which will be part 2 of this series on Ezekiel Calhoun, I’ll continue the chronicle of Ezekiel’s life through his death in 1762 (or possibly 1761), and will discuss his land acquisitions in the Long Cane area of South Carolina and his will and estate papers.

[1] Jean Ewing Calhoun’s name is Jane in some sources: Jean and Jane were more or less interchangeable in Scotland and Ulster at the time.

[2] Mary B. Kegley, Early Adventurers on the Western Waters, vol. 3, pt. 2 (Marceline, Missouri: Walsworth, 1995), pp. 597-8.

[3] Ibid., p. 594.

[4] Ibid. See also A.S. Salley, Jr., “The Grandfather of John C. Calhoun,” South Carolina Historical and Genealogical Magazine 39,1 (January 1938), p. 50, discussing the estate documents and noting that they had been found in the probate court records of Lancaster County by George T. Edson in 1936. A photocopy of Catherine’s relinquishment of administration of the estate is in the John C. Calhoun Papers at South Caroliniana Library of the University of South Carolina in Columbia. Information about these estate documents is also in the Calhoun folders of the Leonardo Andrea Collection (see especially file 128, p. 2).

[5] Kegley, Early Adventurers on the Western Waters, p. 594; and Salley, “The Grandfather of John C. Calhoun,” p. 50. A photocopy of the bond of Ezekiel and William Calhoun and John Noble to administer Patrick Calhoun’s estate is in the John C. Calhoun papers at South Caroliniana library. The original is in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, probate records.

[6] Kegley, Early Adventurers on the Western Waters, p. 593, citing Preston family of Virginia papers, reel 2, folder 34, Library of Congress.

[7] Margaret Ewing Fife, Ewing in Early America, part 1 (Fife, Atlanta, 1995), pp. 141f.

[8] Ibid., p. 144.

[9] Kegley, Early Adventurers on the Western Waters, p. 594.

[10] James Patton’s Woods River Entry Bk. 1746-9 is in the Preston Family Papers: Davie Collection, 1658-1896 at Filson Club Historical Society and is available digitally at the Society’s website. On the Calhoun family’s land acquisitions in Augusta County, Virginia, see also Charles E. Kemper, “Valley of Virginia Notes,” Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 31,3 (July 1923), pp. 250-2.

[11] Virginia Patent Bk. 31, pp. 239-241.

[12] Mary B. Kegley, Wythe County, Virginia, a Bicentennial History (Wytheville, 1989), p. 19.

[13] The letter is transcribed in Correspondence of John C. Calhoun, vol. 2, part 1 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1900), pp. 706-7. See also the Leonardo Andrea collection, files 128, p. 5, and 134, p. 88. The original is in the John Caldwell Calhoun Papers held by Clemson University, folder 285.

[14] See supra, n. 12. The Patton-Preston Notebook is in the Kegley Collection of the Kegley Library at Wytheville Community College.

[15] Augusta County Virginia Court Order Bk. 1, p. 113. See also Kegley, Early Adventurers on the Western Waters, p. 596; and A.S. Salley Jr., “The Calhoun Family of South Carolina,” South Carolina History and Genealogy 7,2 (April 1906), p. 81.

[16] Kegley, Early Adventurers on the Western Waters, p. 596.

[17] Ibid., citing Preston Family of Virginia Papers, Library of Congress, folder 25, file 60.

[18] Kegley, Early Adventurers on the Western Waters, p. 596, citing Lyman Chalkley, Chronicles of the Scotch-Irish Settlement in Virginia, Extracted from the Original Court Records of Augusta County, 1745-1800, vol. 1 (Rosslyn, Virginia: Commonwealth, 1912), pp. 56, 58, 60, 64, 310; and Augusta County, Virginia, Court Order Bk. 3, pp. 404, 420.

[19] Kegley, Early Adventurers on the Western Waters, p. 596, citing Preston Family of Virginia Papers, Library of Congress, folder 25, file 60; Augusta County, Virginia, Court Order Bk. 1, p. 113; and Augusta County, Virginia, Survey Bk. 1.

[20] Augusta County, Virginia, court Order Bk. 1, p. 129. See Kegley, Early Adventurers on the Western Waters, p. 596; and Salley, “The Calhoun Family of South Carolina,” p. 81.

[21] Kegley, Early Adventurers on the Western Waters, p. 596, citing Augusta County, Virginia, court Order Bk. 1, p. 130, and 2, pp. 371, 501.

[22] Salley, “The Calhoun Family of South Carolina,” p. 82, citing Augusta County, Virginia, Court Order Bk. 3, p. 371.

[23] Augusta County, Virginia, Deed Bk. 7, pp. 182-5.

[24] Fife, Ewing in Early America, part 1 (Fife, Atlanta, 1995), p. 144.

[25] Ibid., p. 143.

[26] Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, Will Bk. A, p. 67.

[27] Fife, Ewing in Early America, part 1 (Fife, Atlanta, 1995), p. 143f.

[28] See “John C. Calhoun to Charles H. Allen, November 21, 1847,” Gulf States Historical Magazine 1,6 (May 1903), pp. 439-441.

[29] Bobby F. Edmonds, The Making of McCormick County (McCormick, South Carolina: Cedar Hill, 1999), p. 13. Edmonds may be citing John H. Logan: see infra, n. 34.

[30] Kegley, Early Adventurers on the Western Waters, p. 597.

[31] David Ramsay, History of South Carolina from Its First Settlement in 1670, to the Year 1808, vol. 1 Charleston: Longworth, 1809), pp. 208-9.

[32] Salley, “The Calhoun Family of South Carolina,” p. 83.

[33] See file 128, p. 7, of the Calhoun folders of the Leonardo Andrea Collection.

[34] See John H. Logan, A History of the Upper Country of South Carolina, from the Earliest Periods to the Close of the War of Independence, vol. 1 (Charleston: Courtenay, 1859), p. 150, which states that the Calhouns were induced to visit the Long Canes region by a band of hunters at the Waxhaws.

[35] Edward McCrady, The History of South Carolina under the Royal Government, 1719-1776, vol. 2 (New York: Macmillan, 1899), p. 316.

[36] John H. Logan transcribes this letter in A History of the Upper Country of South Carolina, vol. 2 (Charleston: Courtenay, 1859), pp. 94-7. Similar information is in Monroe Pickens, Cousin Monroe’s History of the Pickens Family (Easley, South Carolina: Day, 1951), p. 40.

[37] Edmonds, The Making of McCormick County, p. 13.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Lester W. Ferguson, Abbeville County: Southern Lifestyles Lost in Time (Spartanburg: Reprint Co., 1993), p. 13.

[40] See Robert L. Meriwether, The Expansion of South Carolina, 1729-1765 (Kingsport, Tennessee: Southern, 1940), pp. 124-5.

[41] Ibid., pp. 125-7; and Mary Catherine Davis, “The Feather Bed Aristocracy: Abbeville District in the 1790s,” The South Carolina Historical Magazine 80,2 (April 1979), p. 137. The deed for the 200,000 acres is in South Carolina Deed Bk S-3, pp. 234-253.

[42] Meriwether, The Expansion of South Carolina, 1729-1765, p. 126.

[43] Jessica L. Cook, “Geography of a Massacre: Cherokee and Carolinian Visions of Land at Long Cane,” University of Virginia History Department master’s thesis, 2017 (unpublished), p. 6.

[44] Ibid., p. 7.

[45] Ibid., p. 5.

3 thoughts on “Ezekiel Calhoun (abt. 1720, Co. Donegal, Ireland — bef. 25 May 1762, Augusta Co., Virginia), Son of Patrick Colhoun and Catherine Montgomery (Part 1)”