A number of the names of the appraisers are ones we’ve met in previous Livingston County records involving Ezekiel. As a previous posting notes, the Gordon and Sanders families had kinship ties to the Harrison family into which Ezekiel married. As another posting shows, Ezekiel sold part of a lot in Smithland to Joseph and David Watts on 27 March 1839, and

Thomas M. Davis is named in a 16 September 1845 mortgage made by William Scott Haynes to John W. Ross and Ezekiel C. Green.[3]

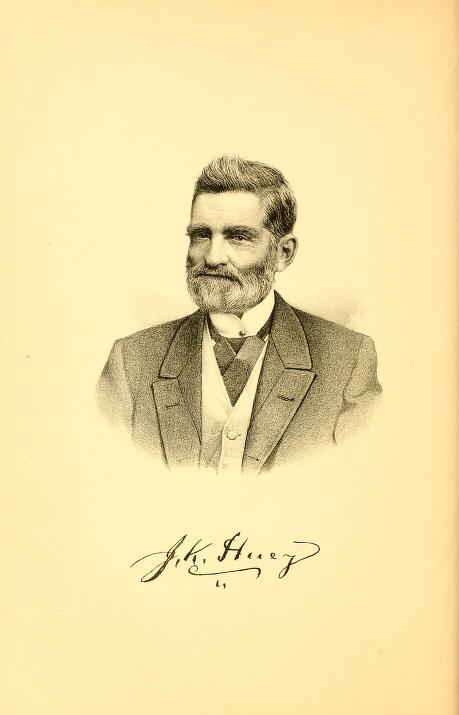

Ezekiel’s Estate Administrator, James K. Huey

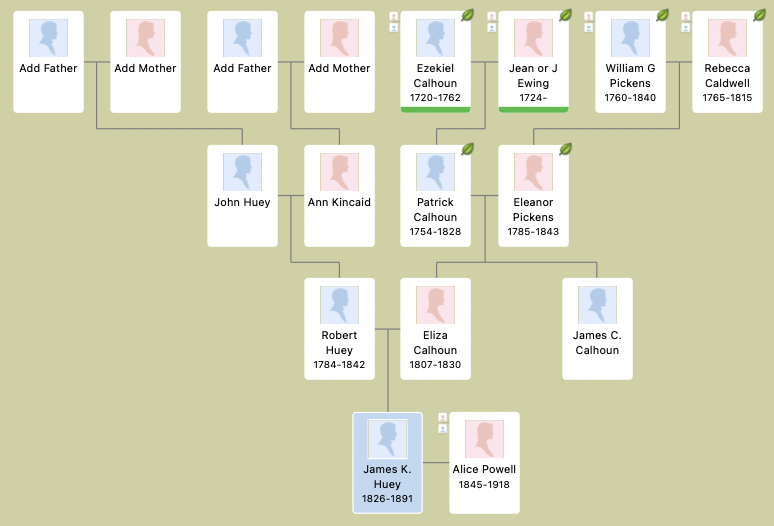

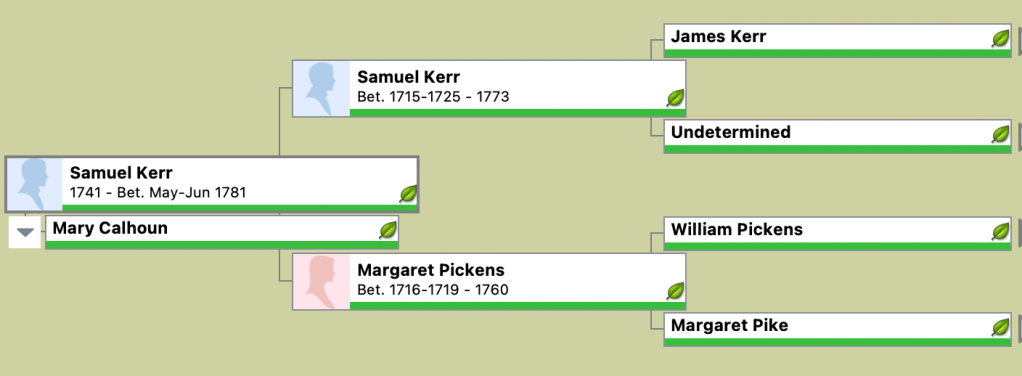

Ezekiel’s estate administrator James K. Huey (1826-1891) deserves attention, too. Huey was a cousin of Ezekiel Calhoun Green. The two were multiply related, in fact. Huey’s parents were Robert Huey (1784-1942) and Eliza Calhoun (1807-1830).[4] Eliza was a daughter of Patrick Calhoun and Eleanor Pickens, both families being part of Ezekiel Calhoun Green’s bloodlines. Patrick’s father was Ezekiel Calhoun (abt. 1720 – 1762) — for whom Ezekiel Calhoun Green was named. Ezekiel Calhoun’s daughter Mary Calhoun, a sister of Patrick Calhoun, married Samuel Kerr, and this couple were the parents of Ezekiel Calhoun Green’s mother Jane Kerr Green. Eliza Calhoun Huey, the mother of Ezekiel’s estate administrator James K. Huey, and Jane Kerr Green, Ezekiel C. Green’s mother, were first cousins.

James K. Huey and Ezekiel C. Green were also cousins in the Pickens family line. William Gabriel Pickens, father of James’s grandmother Eleanor Pickens Calhoun, was a first cousin of Ezekiel’s grandfather Samuel Kerr, whose mother Margaret Pickens Kerr was a sister to John Pickens, father of William Gabriel Pickens. To add to the complexity of this tangle of family connections, it might also be noted that John Pickens married Eleanor Kerr, a sister of Samuel Kerr’s father Samuel Kerr elder, who married Margaret Pickens.

Patrick Calhoun, uncle of Ezekiel C. Green’s mother Jane Kerr Green, and Patrick’s father-in-law William Gabriel Pickens, first cousin of Ezekiel’s grandfather Samuel Kerr, came to Livingston County from South Carolina earlier than Ezekiel C. Green did. It’s possible that in choosing to move there from Pendleton District, South Carolina, Ezekiel was following these relatives to Livingston County. I haven’t determined exactly when Patrick Calhoun and William Gabriel Pickens arrived in Kentucky from South Carolina, but I spot them in Livingston County records some years prior to Ezekiel’s arrival there. Unfortunately, in a Revolutionary pension affidavit he gave in Livingston County on 4 February 1833, when William Gabriel Pickens stated the year in which he moved to Livingston County from Abbeville District, South Carolina, he left the year blank — or the clerk recording this information did so.[5]

There is also confusion in a number of DAR and SAR applications noting that Patrick Calhoun with wife Eleanor Pickens moved from South Carolina to Livingston County, Kentucky. A number of these applications confuse the Patrick Calhoun who was son of Ezekiel Calhoun — this is the Patrick who moved to Livingston County — with the uncle of this Patrick Calhoun, a man also named Patrick Calhoun who was father of John Caldwell Calhoun. As Rockwell D. Hunt notes in his biography of California Judge Ezekiel Ewing Calhoun, a son of Patrick Calhoun and Eleanor Pickens, E.E. Calhoun’s father Patrick was a first cousin of John C. Calhoun.[6] The biography of James K. Huey in Battle, Perrin, and Kniffin’s history of Kentucky makes the same point.[7]

James K. Huey was a lawyer and judge in Livingston County who served as a representative to the Kentucky legislature. Following the Civil War, he moved to New Orleans, where he had a commission business, then he and his wife and children returned to Livingston County after some years, with Huey dying in Smithland on 31 December 1891.[8] I suspect that James’s middle name was Kincaid, by the way.

Sale of Ezekiel’s Personal Property in Livingston County

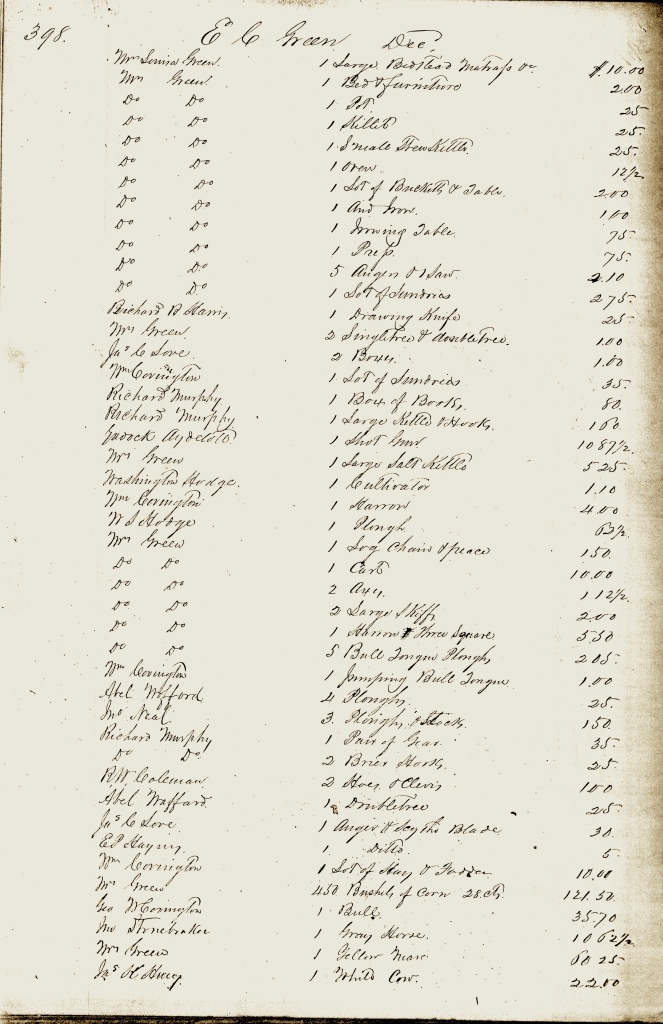

James K. Huey conducted the sale of Ezekiel C. Green’s personal property in Livingston County on 22 October 1851, filing the sale account on 3 November 1851.[9] The sale account (the first page of the account is at the head of the posting) indicates that Ezekiel was a comfortably placed farmer with a well-furnished house and farm, a house whose furniture included looking glasses, picture frames, clocks, maps, wardrobes, side tables, Windsor chairs, and other accoutrements of a middle-class farm family in this time and place. Among the other items sold at the estate sale were 450 bushels of corn — perhaps grown on the cotton and corn plantation Ezekiel had bought in Mississippi several years before his death, something I’ll discuss later. The primary buyer at the sale was Ezekiel’s widow Louisa, who had not yet married her next husband Milton Henderson Carson, since she is listed in the sale bill Mrs. Green.

In the estate sale account, I note the absence of the four enslaved people whom Ezekiel held in Livingston County on the 1850 federal slave schedule, a mulatto woman aged 40, and three Black males aged 21, 15, and 5.[10] I find no mention of these enslaved persons in any of Ezekiel’s estate records. In the 1850 slave schedule, the columns “Fugitive from the State” and “Number manumitted” both have a mark next to the mulatto enslaved woman aged 40. I’m not entirely sure what this means: Had Ezekiel manumitted this enslaved woman by 1850?

The 1860 federal slave schedule shows Ezekiel’s widow Louisa holding nine enslaved people in Smithland, and her now husband Milton H. Carson holding five enslaved people.[11] None of the nine enslaved persons listed with Louisa on this slave schedule appears to match any of the enslaved persons Ezekiel C. Green held in 1850. The same slave schedule shows Ezekiel’s son by Matilda Harrison, Samuel K. Green, holding an enslaved person, and James L. Warmack, husband of Ezekiel’s daughter by Louisa, Mary Musa Green, holding six enslaved persons, none of these persons belonging to Samuel K. Green or James L. Warmack appearing to match the enslaved persons owned by Ezekiel K. Green in 1850.

On 3 November 1851, James K. Huey presented the bill of the sale of Ezekiel C. Green’s personal estate to county court and this was recorded.[12] The estate inventory was filed the same day.[13] On 1 March 1852, Huey produced a list of notes owing to the estate, and on the same day, the court appointed Washington Beverly, John Snyder, Thomas M. Davis, and Blount Hodge commissioners to allot to Louisa B. Carson her dower in her husband’s Cumberland Island land.[14] On 3 January 1853, Snyder, Beverly, and Davis reported to court that they had allotted Louisa her dower rights in the Cumberland Island property.[15]

On 7 February 1853, Huey filed an estate settlement.[16] On 7 March, the court approved the settlement report.[17] On 4 April 1853, on motion of James K. Huey, the court issued a summons against John and Samuel Green, heirs of Ezekiel C. Green, to be returned at the first day of the next court, showing why a guardian should not be appointed for them.[18] Both John and Samuel were minors, John being 15 and Samuel 14. The estate records indicate that at some point between 22 October 1851, when the estate sale was held, and 7 February 1853, when an estate settlement was filed, Ezekiel’s widow Louisa had remarried to Dr. Milton H. Carson. Since Louisa’s daughter by Ezekiel, Mary Musa Green, was her child, I think Mary Musa would not have needed a guardian appointed. But as sons of Ezekiel by wife Matilda Harrison, being raised by a stepmother now married to a new husband, John and Samuel did.

Louisa’s husband Milton H. Carson was born 20 June 1807 in Dandridge (Jefferson County), Tennessee, and died 9 December 1886, according to his tombstone in Smithland cemetery.[19] The 1860 federal census shows him and wife Louisa B. living in Smithland where he’s listed as a physician with $2,700 real worth and $$7,000 personal worth.[20] Louisa has $5,200 real worth and $12,500 personal worth. Living in the household are Milton Carson’s son William Mitchusson Carson by his first wife Sinai Young Mitchusson, who is a druggist, Milton Carson’s daughter Emily, Louisa’s daughter by Ezekiel C. Green, and Louisa’s daughter by husband Timothy J. Alvord, Julia V. Mitchell, with her son John. Ezekiel’s sons John K. and Samuel K. Green were enumerated in Smithland in a separate household in 1860, one headed by Samuel, who had married Emma Augustine Burnham in Warren County on 28 April 1859, points I’ll discuss in a later posting. Louisa’s daughter by Ezekiel C. Green, Mary Musa, had also married by 1860 and was living in Smithland with husband James L. Warmack.

Ezekiel’s Coahoma County, Mississippi, Property

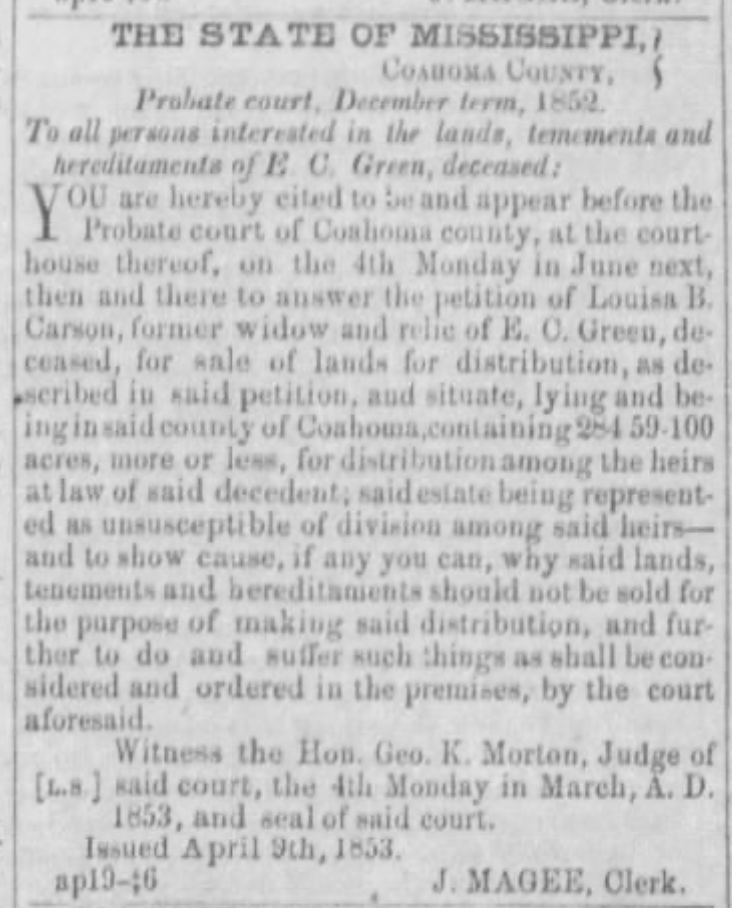

On 9 August and 6 September 1853, the Vicksburg Daily Whig carried a notice that Louisa B. Carson (late Green) and her husband Milton H. Carson had petitioned to sell 284.59 acres on Yazoo Pass in Coahoma County, Mississippi, land in which John K. Green and Samuel K. Green, minor heirs of Ezekiel under guardianship of J. Magee, had an interest: John and Samuel are named in the 6 Sepember notice.[21] This was land — lots 3, 6, 7, 12, and 13 in section 14, township 29, range 3 west at Yazoo Pass — that Ezekiel had bought for $1,800 from Peyton R. Gray and wife Margaret Susan on 26 February 1848.[22] The deed states that Ezekiel C. Green lived in Livingston County, Kentucky. Milton H. Carson and wife Louisa sold this land on 2 January 1854 for $2,000 to Jonathan P. Simms of Jackson, Mississippi, with the deed stating that the Carsons lived in Livingston County, Kentucky, and that Louisa was the widow and relict of Ezekiel C. Green.[23] James Lusk Alcorn, who was discussed previously and whose father James Alcorn was the guardian of Mary Peet when Ezekiel married her in Livingston County in December 1832, witnessed this deed. The deed further states that at the time of Ezekiel C. Green’s death, he had a cotton and corn plantation on this land in Coahoma County, Mississippi. The 1850 federal slave census shows Ezekiel holding twelve enslaved people in Coahoma County.[24] James Alcorn is listed on the same page of this slave schedule.

Coahoma is a Mississippi Delta county in northwest Mississippi south of Memphis, with the Mississippi River forming its western border and Arkansas across the river. It’s some 260 miles south of Smithland, but with the direct connection between the two places due to the Ohio and Mississippi River systems, in the era of steamboat travel, the two places would have been fairly easily accessible to each other. James Lusk Alcorn moved from Livingston County, Kentucky, to Coahoma County, Mississippi, in 1844, setting up a law office at Delta (later Friars Point) in Coahoma County and building a three-story house in 1850 on his Mound Place plantation, where he was the second largest planter in the state with nearly 100 enslaved persons by 1860. Yazoo Pass, the stream on which Ezekiel’s land was located, joins the Mississippi River in northwestern Coahoma County north of the county seat of Clarksdale near Alcorn’s Mound Place plantation.[25] It appears to me that Ezekiel’s decision to buy a plantation in Coahoma County in 1848, four years after James Lusk Alcorn moved there from Livingston County, had much to do with his connection to Alcorn.

The deed for this Coahoma County land also states that the land was sold pursuant to an order of the probate court on the 4th Monday in September 1853, and that Louisa had a third share of the land as her dower interest.[26] The deed does not mention Ezekiel’s sons John and Samuel, who held the other two-thirds share but were still minors at this point. Presumably, Louisa was selling the land on their behalf as well as her own. L.L. Bridgers, acting as county sheriff and administrator de bonis non for Ezekiel’s estate in Coahoma County, conveyed the deed to Simms.

Final Livingston County Estate Documents for Ezekiel

On 5 September 1853, Huey filed another estate settlement report.[27] This report was approved on 3 October 1853.[28] On 4 October, the court ordered Huey as estate administrator to pay to Mrs. Carson formerly Green $112 with interest for the rent of “the farmhouse” (evidently in Livingston County) from an unspecified date in 1852, money that had wrongfully been paid to the estate for the heirs and not directly to Louisa Carson.[29] A marginal note says that the order was copied and certified on 6 May 1854.

Livingston County court minutes state that at court held on 6 February 1854, Milton H. Carson produced an account for his guardianship of Mary M. Green, showing that he had paid $120 for washing, mending, and making her clothes in 1852-3, $11.85 for sending her to William Moore for schooling, and $10 for sending her to school to Miss Helen Simpson.[30] The court ordered James K. Huey as estate administrator to pay Carson $141.85 to reimburse him for these expenses.

On 3 April 1854, Louisa B. Carson presented to court accounts for her expenses incurred on behalf of Ezekiel’s heirs John K. and Samuel K. Green, showing that she had spent $60 on each for board, lodging, washing, making and repairing clothes from 10 April to 6 November.[31] The court ordered that these proven expenses were to be certified and James K. Huey was to reimburse Louisa Carson.

On 2 April 1855, Huey filed another report of the estate settlement.[32] On 2 July 1855, the court order book reports that on 27 June 1855, Huey had petitioned the court to be relieved of administering the estate.[33] At the same July 1855 court session, Milton H. Carson a filed a report of estate settlement and Thomas M. Davis was appointed administrator de bonis non, having given oath with W.P. Fowler as his security.[34]

Court minutes for 3 May 1857, reference a lawsuit that Ezekiel’s son Samuel K. Green had filed against Milton H. Carson, evidently regarding the estate of Ezekiel Calhoun Green, though the brief court notice provides no details about the case.[35] On 6 July 1857, the court order book notes that the case had been dropped.[36]

Finally, on 1 February 1858, court minutes report that Milton H. Carson had filed another estate report.[37] On 3 May 1858, Thomas M. Davis filed another report.[38] This is the last record I find of this estate in Livingston County. By this date, as I noted previously, Ezekiel’s son Samuel K. Green and daughter Mary Musa Green had married and were, per the 1860 census, living in their own households in Smithland, with Samuel’s brother John living with him.

As noted previously, Ezekiel was named for his great-grandfather Ezekiel Calhoun (abt. 1720 – 1762), grandfather of Ezekiel’s mother Jane Kerr, whose mother Mary Calhoun was a daughter of Ezekiel. The given name Ezekiel long passed down family lines descending from Ezekiel Calhoun, and was, as previously noted, the name given by Ezekiel Calhoun Green’s brother Samuel Kerr Green to his first-born son. Ezekiel Calhoun was born in County Donegal, Ireland, and came with his parents Patrick Calhoun and Catherine Montgomery to Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, in 1733. Following Patrick’s death in that county in 1741, Catherine and their children moved to Virginia by the fall of 1745, settling a few years in Augusta County on land that eventually fell into Wythe County before moving in 1756 to the Long Cane area of what is now McCormick County, South Carolina.

Ezekiel was living in the Long Cane settlement in 1762 when he was killed at some time before 25 May as he was visiting lands he still held on Reed Creek in Augusta (later Wythe) County, Virginia. He is said to have been shot by an unknown assailant who was lurking in the woods as Ezekiel stood in the door of a cabin on his property. Ezekiel was buried near that spot. Various records indicate that he was a highly esteemed man in his community on the Long Cane in South Carolina, which was comprised largely of people with Ulster Scots roots similar to his own, many of them his kinfolks. Family tradition indicates that he had uncommon knowledge and ability to treat many of the illnesses that afflicted his family members and friends. Ezekiel’s granddaughter Floride Bonneau Colhoun married her cousin John Caldwell Calhoun, a son of Ezekiel’s brother Patrick Calhoun, who played prominent roles in national politics as U.S. vice-president and senator from South Carolina. Floride’s father was Ezekiel’s son John Ewing Colhoun, a sister of Mary Calhoun Kerr, grandmother of Ezekiel Calhoun Green.

[1] Livingston County, Kentucky, Court Order Bk. L, p. 28.

[2] Ibid. The court minutes state that a copy of the appointment of appraisers was delivered to James K. Huey on 21 October 1851.

[3] On Thomas M. Davis, see J. H. Battle, W. H. Perrin, and G. C. Kniffin, Kentucky: A History of the State, vol. 2 (Louisville: Battey, 1885), p. ? — see “Biography of Dr. Frank T. Davis McCracken County, Kentucky,” USGenweb archives for McCracken County, Kentucky; and Brenda Joyce Jerome, “Thomas M. Davis Burial Plot,” Western Kentucky Genealogy Blog.

[4] Battle, Perrin, and Kniffin, Kentucky: A History of the State, vol. 2, pp. 823-4; Jerome, “Col. James K. Huey (1826 – 1891),” Western Kentucky Genealogy Blog; and Find a Grave memorial page of Col. James K. Huey, Smithland cemetery, Smithland, Livingston County, Kentucky, created by Charles Lay, maintained by Jim Nelson, with a tombstone photo by BJJ. James K. Huey’s grandmother Ann Kincaid Huey left a will in Livingston County dated 15 March 1828 naming James’s father Robert Huey as Ann’s son: Livingston County, Kentucky, Will Bk. 1, pp. 107-9.

[5] NARA, Case Files of Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Applications Based on Revolutionary War Service, compiled ca. 1800 – ca. 1912, documenting the period ca. 1775 – ca. 1900, RG 15, S1244, file of William Gabriel Pickens, Livingston County, Kentucky, available digitally at Fold3.

[6] Rockwell D. Hunt, ed. California and Californians, vol. 3 (Chicago: Lewis, 1932), pp. 68-70.

[7] Battle, Perrin, and Kniffin, Kentucky: A History of the State, vol. 2, p. 823.

[8] Ibid., and Jerome, “Col. James K. Huey (1826 – 1891),” Western Kentucky Genealogy Blog.

[9] I have a photocopy of the sale account from source that is unfortunately not identified, pp. 397-9. The account is evidently recorded in a Livingston County probate book that is not available digitally at FamilySearch, and I’m not sure how I obtained this record.

[10] 1850 federal slave schedule, Livingston County, Kentucky, Smithland, p. 301 (#23, 26 August).

[11] 1860 federal slave schedule, Livingston County, Kentucky, Smithland, p. 12 (#7 and 12, 24 August to 4 September.

[12] Livingston County, Kentucky, Court Order Bk. L, p. 48.

[13] The account of the sale of Ezekiel’s personal estate (see supra, n. 103) is preceded by a record showing that James K. Huey filed the estate appraisement on the same day he filed the bill of sale, 3 November 1851.

[14] Livingston County, Kentucky, Court Order Bk. L, p. 59.

[15] Ibid., p. 118.

[16] Ibid., pp. 126-7.

[17] Ibid., p. 135.

[18] Ibid., p. 141.

[19] See Find a Grave memorial page of Dr. Milton H. Carson, Smithland cemetery, Smithland, Livingston County, Kentucky, created by Charles Lay, maintained by Bill Haseltine, with a tombstone photo by BJJ. The tombstone gives Milton H. Carson the title Dr.

[20] 1860 federal census, Livingston County, Kentucky, Smithland, p. 289 (dwelling 724/family 736; 25 August).

[21] Vicksburg Daily Whig (Vicksburg, Mississippi) (9 August 1853), p. 2, col. 6; and (6 September 1853), p. 1, col. 6.

[22] Coahoma County, Mississippi, Deed Bk. D, pp. 99-101.

[23] Ibid., Deed Bk. E, pp. 431-2.

[24] 1850 federal slave schedule, Coahoma County, Mississippi, pp. 6-7 (#38, 18-19 September).

[25] See Harry Abernathy, “Once rich, always Rich…,” The Clarksdale [Mississippi] Press Register (8 August 1992), p. 1, noting that Alcorn was the earliest settler of the community of Rich on the Yazoo Pass, and that he settled on a quarter section of land on Yazoo Pass when he came from Kentucky to Mississippi in the 1840s, this site becoming his Mound Place plantation.

[26] Coahoma County’s Index to Estates of Decedents, Minors, Lunatics, and Convicts … (1839 – 1880), available digitally at FamilySearch, index documents filed in the county for the estate of Ezekiel C.. Green, including letters of administration to James K. Huey, a bill of sale for the estate, the allotment of dower to Louisa Carson, appointment of guardians for John K., Samuel K., and Mary M. Green, and reports of the estate settlement. But these citations point to process and proceedings records that I do not find among the digitized probate records of the county at FamilySearch. Also indexed here seems to be litigation that occurred, evidently among Ezekiel’s sons and their step-mother, about the handling of estate matters.

[27] Livingston County, Kentucky, Court Order Bk. L, p. 157.

[28] Ibid., p. 164.

[29] Ibid., p. 166.

[30] Ibid., p. 178.

[31] Ibid., p. 190.

[32] Ibid., p. 247.

[33] Ibid., p. 259.

[34] Ibid., pp. 261-2.

[35] Ibid., p. 383.

[36] Ibid., p. 392.

[37] Ibid., p. 429.

[38] Ibid., p. 443.

One thought on “Children of John Green (1768-1837) and Jane Kerr (1768-1855): Ezekiel Calhoun Green — Estate Documents”