Of these children, Samuel and Ezekiel did not join their parents in the move from Pendleton District, South Carolina, to Alabama in the fall of 1818, but went to Tennessee, with Ezekiel then settling in Kentucky and Samuel moving from Tennessee to Arkansas Territory (briefly) and then to Louisiana, and finally dying in Texas. Elizabeth (with husband James Thompson), Benjamin, Jane Caroline (with husband Thomas Keesee), and George Sidney moved from Bibb County, Alabama, to Arkansas, with Benjamin and Jane and Thomas Keesee moving on to Texas. Mary (with husband Robert Wilson Woods), Joscelin, Lucinda, John Ewing, and James Hamilton remained in Bibb County with their parents, with Mary, Joscelin, Lucinda, and John Ewing predeceasing their mother Jane, and with James inheriting the house his father and brother John built in Bibb County between 1830 and 1834.

1. Samuel Kerr Green: I’ve discussed Samuel Kerr Green’s life in detail in a number of previous postings — here, here, here, here, here, here, and here.

2. Elizabeth B. Green was born about 1791 in Pendleton District, South Carolina, and died between 4 August 1868 and 31 August 1870 in Freeo township, Ouachita County, Arkansas. The 1791 birthdate for Elizabeth is indicated by the 1850 and 1860 federal censuses, both of which enumerate her with husband James at Freeo in Ouachita County and state that she was born in South Carolina.[1] The 4 August 1868 date as the terminus a quo for Elizabeth’s death is when her husband James Thompson made his will at Freeo, stating that Elizabeth was still living and was to inherit his estate.[2] The 31 August 1870 date as the terminus ad quem for Elizabeth’s death is the date on which James Thompson was enumerated on the federal census in Freeo township.[3] The census lists James as a widower and shows him living alone.

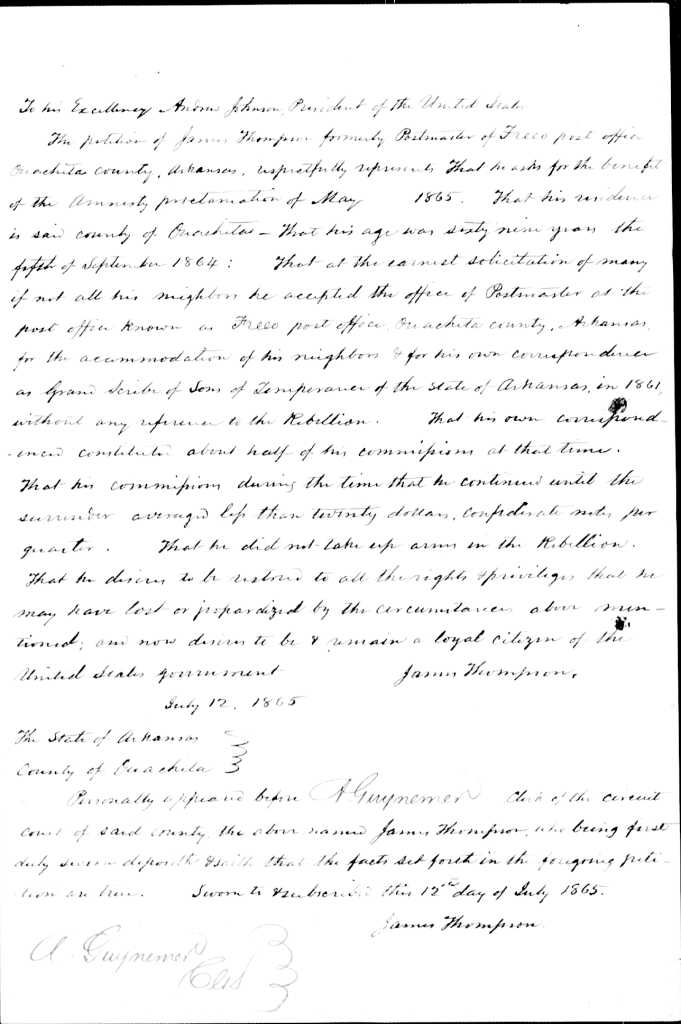

James Thompson’s date of birth is indicated in his 12 July 1865 petition to President Andrew Johnson asking for amnesty due to his service as postmaster at Freeo during the Civil War, service considered an act aiding the Confederacy and paid for by the Confederate government.[4] In the petition, James states that he was sixty-nine years old the 5th of September 1864. This yields a birthdate of 5 September 1795. Federal censuses from 1850 to 1870 all point to a birthdate of 1794-5 for James and all state that he was born in Kentucky.[5]

James Thompson died prior to 21 July 1883 when his will was filed for probate in Dallas County, Arkansas.[6] I have not been able to locate James on the 1880 federal census. The last document I’ve found for him prior to the probate of his will in July 1883 is his acknowledgment of a deed in Ouachita County on 7 November 1876.[7] This document, which I’ll discuss in detail below, and another 1876 document I’ll also discuss later, both indicate that James was still living at Freeo in Ouachita County in 1876. I assume that this is where James died, but do not have absolute proof of that fact. Freeo is in northeast Ouachita County about two miles south of the border of Dallas County, which is contiguous to Ouachita on the north.[8] I think that James’s will was filed in Dallas County because he probably died owning property in that county as well as in Ouachita County, where I do not find a will or estate records for him.

Elizabeth B. Green married James Thompson on 17 August 1830 in Tuscaloosa County, Alabama.[9] I think it’s very likely that this James Thompson is a man of that name enumerated on the 1830 federal census in Tuscaloosa County aged 30-39, with no one but himself in his household.[10] James is enumerated next to R.E.B. Baylor. Robert Emmett Bledsoe Baylor (1793-1874), a co-founder of Baylor University, was born in Lincoln County, Kentucky, on 10 May 1793 and moved to Tuscaloosa County in 1820-1, after serving in the Kentucky House of Representatives.[11] In 1824, Baylor was elected to the Alabama House of Representatives, and in 1829, to the U.S. Congress.

Immediately prior to James Thompson on the 1830 federal census is Elias Jenkins (1802-1876), who married Jane Keesee on 22 December 1831 in Tuscaloosa County. Jane’s brother Thomas Keesee married Elizabeth B. Green’s sister Jane Caroline Green, and Thomas and Jane Keesee’s sister Agnes, who married Benjamin Clardy, was the mother of Mary Ann Clardy, who married George Sidney Green, a brother of Elizabeth and Jane Caroline Green. According to Matthew William Clinton in his history of the early days of Tuscaloosa, Elias Jenkins had a store with John B. Jenkins in Tuscaloosa by 1819 on the corner of Broad Street and Greensboro Avenue.[12] Elias Jenkins was born in 1802 in Tennessee.

Note that James Thompson’s will (see the discussion below) states that he bought a pony from his sister Mary to bring Robert Gilkinson from Kentucky to Alabama in October 1827. This information in the will makes me wonder if it was in October 1827 that James made his move from Kentucky to Tuscaloosa County.

As a previous posting notes, when Elizabeth Green Thompson’s brother John Ewing Green petitioned for division of the real property of John Green in Bibb County, Alabama, in February 1838, the petition named Elizabeth Green as wife of James Thompson and as one of the estate heirs.[13] The final account of John Green’s estate that John E. Green presented to court on 7 May 1839 also names Elizabeth, wife of James Thompson, as an heir of John Green’s estate.[14]

A household headed by James Thompson appears on the 1840 federal census in Bibb County, Alabama.[15] The census listing gives this James Thompson a Jr. designation. The household contains two males -10, one male 10-15, and one male 30-40, with one female 5-10, one female 10-15, and one female 30-40. The 1850 and 1860 federal censuses show James and Elizabeth Green Thompson with no children, and I’ve seen no other documents indicating that the couple had children. So if this is the household of James and Elizabeth Green Thompson, then I wonder who the younger members of the household might be.

Elizabeth and James Move from Alabama to Arkansas by 1842

By 1842, James and Elizabeth had left Alabama and moved to Arkansas, where James was the deputy clerk for Pulaski County, whose county seat is Little Rock, from 1842-4, according to a 3 March 1876 article in the Little Rock newspaper Arkansas Gazette.[16] The article states that “Judge James Thompson, of Freeo, Ouachita county, an eighty year old Arkansas veteran” had arrived in Little Rock the preceding day and visited the Gazette office. It also reports that James Thompson had served as deputy clerk for Pulaski County from 1842-3. Articles in Little Rock newspapers in the period 1842-4 contain repeated legal notices signed by James Thompson, D.C., of Pulaski County. I have found no record of military service for James, by the way.

James may simultaneously have functioned as the deputy clerk of both Pulaski and Saline Counties, Saline being contiguous to Pulaski on the west: the Saline County Circuit Court’s Common Law Bk. A states that at that court’s session on 25 April 1842, James Thompson, Esq., was sworn in as deputy clerk of the Saline court (p. 297). On 24 March 1846, Bk. B of this court’s minutes state that Alfred R. Hockersmith and James Thompson were sworn in as deputy clerks to Green B. Hughes, clerk of this court (p. 123).

Note that in the summer of 1837, Elizabeth Green Thompson’s siblings Jane Caroline Green with husband Thomas Keesee, Benjamin S. Green, and George Sidney Green all moved from Bibb County, Alabama, to Saline County, Arkansas. I wonder if James and Elizabeth Green Thompson accompanied her siblings on that move to Arkansas. If so, I do not find James Thompson on the 1840 federal census in Arkansas.

The Move to Freeo, Ouachita County, about 1846: James Assumes Postmaster’s Position and Helps Establish White Spring Cumberland Presbyterian Church

It appears that by 1846, James and Elizabeth had moved from Pulaski County in central Arkansas to Freeo in Ouachita County in south Arkansas. Records indicate that a post office was established at Freeo in 1846. James’s 12 July 1865 amnesty petition to President Andrew Johnson states that when he settled in Freeo, neighbors asked him to establish a post office and take the position of postmaster, which he accepted for their sake and also to allow him to carry on his correspondence as Grand Scribe for the Sons of Temperance in Arkansas.[17]

Guides to U.S. post offices show James Thompson functioning as postmaster at Freeo through the latter part of the 1840s into the mid-1860s, after which he was removed from this position when his petition for amnesty was rejected, a point I’ll discuss later.[18]

Note that the 6 March 1871 deed of James Thompson and others as trustees of the White Spring Cumberland Presbyterian Church at Freeo, which I’ll discuss in detail below, suggests that James was probably an organizing member and perhaps an elder of the White Spring church when William T. Wall conveyed land for the church and a graveyard to Martin Sparks, Jesse H. Sparks, and James Thompson on 2 August 1847.[19] Martin Sparks and his brother Nathan, both of whom are named in this deed, were both ministers of the Cumberland Presbyterian church; the deed suggests to me that Martin Sparks may have been the first pastor of the White Spring church.[20] According to Paul E. Sparks, Martin Sparks, who had previously lived in Tennessee and Illinois, came to Arkansas around 1840 and appears on the 1850 federal census in Ouachita County.[21] The White Spring church had definitely been organized by October 1847, since the presbytery met at White Spring in Ouachita County on 2-4 October 1847, according to Thomas H. Campbell’s history of Cumberland Presbyterians in Arkansas.[22]

Not long after James and wife Elizabeth moved to Ouachita County, on 15 April 1847 at the house of Robert Calvert in Saline County, Henry S. Dawson and wife Frances of Hot Spring County sold James land in Saline County (Saline County, Arkansas, Deed Bk. C, pp. 102-3). The deed states that James Thompson was formerly of Little Rock but now of Ouachita County. As a previous posting notes, Robert Calvert’s wife Mary Keesee was a sister of Thomas Keesee (1804-1879), who married Jane Caroline Green, a sister of James Thompson’s wife Elizabeth B. Green. Elizabeth and Jane Caroline’s brother George Sidney Green married Mary Ann Clardy, whose mother Agnes Keesee Clardy was a sister of Thomas Keesee. The Saline County land James Thompson bought from the Dawsons was 167.68 acres in section 12, township 1 south, range 15 west, near land purchased by Elizabeth B. Green Thompson’s brother Benjamin S. Green after he moved to Saline County in the latter part of the 1830s.

Tracking residents of Ouachita County prior to 1875 is a challenge, since Ouachita County’s early records burned in a courthouse fire at the county seat of Camden in 1875. Deed and other county records are now extant only from 1875, with the rare exception of some county tax records in the period 1846-1850, which Yvonne Spence Perkins has heplfully abstracted in a volume entitled Early Ouachita County Tax Records, 1846-1850 (Perkins, Camden, Arkansas, 1989). These show James Thompson taxed in Ouachita County from 1846-1850, for a poll tax and no land from 1846-1849, and in 1850 for 160 acres in section 6, township 11, range 15. This is the tract to which James received title from James Fleming Fagan in 1851: see below. These early tax records confirm, then, that James and Elizabeth Thompson had settled in Ouachita County by 1846. This move apparently occurred after 24 March 1846, when Saline County circuit court minutes state that Alfred R. Hockersmith and James Thompson were sworn in as deputy clerks to Green B. Hughes, clerk of this court (Saline County, Arkansas, Circuit Court Common Law Bk. B, p. 123).

As I’ve noted previously, the 1850 and 1860 federal censuses show James and Elizabeth Green Thompson living at Freeo with no children in their household.[23] On both of these censuses, their household contains a female named Mrs. D. Miller who is listed as a widow, and who was born in Tennessee in 1820. I have been unable to identify her or even to find her given name. In 1870, when James is listed as widowed and alone in his household at Freeo on the census, D. Miller is two households away.[24] The 1850 and 1860 censuses give James the occupation of farmer; in 1870, he’s listed as a lawyer. As I noted above, the 3 March 1876 Arkansas Gazette article noting that James Thompson of Freeo was in Little Rock gives him the title of judge.[25] James is also given the title of judge in a 29 November 1854 notice stating that he had organized a Sons of Temperance chapter in Little Rock the preceding Monday.[26] The notice states that James lived in Ouachita County.

James Buys Land and Is Active as Grand Scribe of Sons of Temperance

James was serving as Grand Scribe of the Arkansas chapter of the Sons of Temperance by 25 October 1850, when a notice in the Arkansas Gazette regarding an upcoming meeting of the Grand Division of the Sons of Temperance at Princeton in Dallas County on 28 October was published by James Thompson, G. Scribe.[27] Princeton is sixteen miles north of Freeo, both places being on the Camden-to-Princeton road that is now Arkansas highway 9, with Freeo a bit to the east of the road.

On 1 April 1851, James F. Fagan assigned James Thompson a military warrant for 160 acres of land in Ouachita County that Fagan had received for service in the Mexican War.[28] This land was in Freeo township in the northeast corner of Ouachita County on the Dallas County line.

James Fleming Fagan (1828-1893) was a native of Clark County, Kentucky, whose parents moved from Kentucky to Little Rock in 1838. He served as a lieutenant from Arkansas during the Mexican War before returning to Arkansas to run his stepfather’s farm in Saline County, where, as I’ve indicated previously, several of Elizabeth Green Thompson’s siblings spent time. In 1852-3, he served in the Arkansas House of Representatives, and in 1860-2 in the Arkansas Senate. He was a Confederate general during the Civil War and a federal marshal following the Civil War.[29]

On 2 May 1854, the True Democrat of Little Rock reported that, at a meeting of the Ouachita County Democratic Convention at Camden, the seat of Ouachita County, on 3 April 1854, James Thompson of Freeo was appointed to make nominations of candidates for the U.S. Congress and the Arkansas legislature.[30] On 6 April 1858, the True Democrat carried a statement by James Thompson of Freeo dated 31 March 1858 that the Ouachita County Democratic Convention at Camden had recommended Rust for Congress on the 29th.[31]

James Thompson continues as Grand Scribe of the Arkansas chapter of the Sons of Temperance in newspaper notices in the 1850s. On 9 August 1854, Little Rock’s True Democrat carried a notice written by James Thompson as Grand Scribe that the Sons of Temperance would be meeting at Princeton in Dallas County on the fourth Monday in October, with a public procession and addresses on Wednesday followed by a dinner.[32] On 4 October 1856, the Arkansas Gazette published a notice by James Thompson, G.S., that the Sons of Temperance would meet at Little Rock on the fourth Monday of November.[33] And on 2 December 1856, the True Democrat of Little Rock carried a statement written by James Thompson on 28 November reporting on the November meeting in Little Rock and identifying officers of the Sons of Temperance in Arkansas.[34] Once again, James appears in the notice as G.S. of the Sons of Temperance in Arkansas.

The 4 October 1856 notice of a Sons of Temperance meeting at Little Rock is noteworthy because immediately above it is printed a notice by James Thompson, Stated Clerk, that the Bartholomew presbytery of the Cumberland Presbyterian church would meet on Friday before the first Sunday of November at Ware’s schoolhouse twelve miles south of Hamburg in Ashley County.[35] Though Hamburg was some eighty miles south of Freeo, I think it’s very possible the James Thompson who was clerk of the Bartholomew presbytery and who published this notice is the same James Thompson who was grand scribe of the Sons of Temperance and who lived at Freeo. White Spring church to which James belonged was in the Bartholomew presbytery by 1856.[36]

Meanwhile, James continued acquiring land. On 1 September 1856, he had a certificate for 40 acres in Dallas County (Arkansas Pat. Bk. 120, p. 342). This land was in section 34 of township 10 south, range 15 west. This land was just across the Ouachita County line in Dallas County. The certificate identifies James Thompson as a resident of Ouachita County.

On 15 June 1857, Abner Garner assigned 40 acres of land in Ouachita County to James Thompson.[37] This land had been granted to Garner by warrant 93-148 for service in Captain Stephens’ company, Tennessee militia, during the War of 1812.

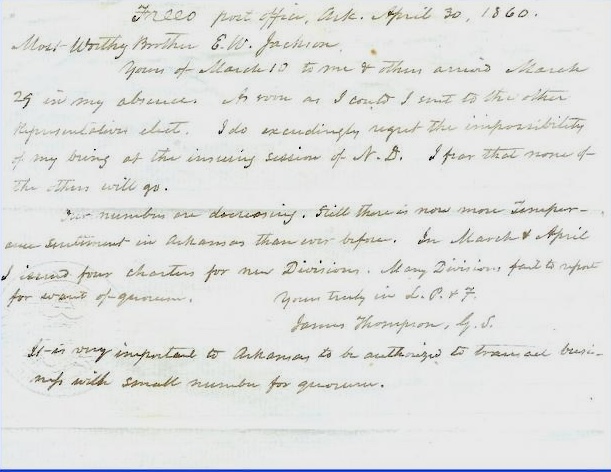

I have a digital image of a 30 April 1860 Sons of Temperance letter written by James Thompson from Freeo post office in Ouachita County to “Most Worthy Brother E.W. Jackson,” in response to a letter of Jackson’s sent to James on the 10th. The letter was on sale at EBay in January 2014. It speaks of representatives elect and a session of N.D. (the National Division) of the Sons of Temperance. The letter is signed, “Yours Truly in L., P., & F.,” “James Thompson, G.S.”

On 24 August 1861, the True Democrat carried a letter from James Thompson of Freeo dated 24 August to Messrs. R.S. Yerkes & Co. stating that the mail had arrived at Freeo on the 23rd with a packet that he assumed was for Camden and other places in Ouachita County, and the packet was “well saturated with whiskey.”[38]

After Civil War, James Applies for Amnesty Due to Service as Freeo Postmaster

As I noted previously, on 12 July 1865, James Thompson applied to President Andrew Johnson for amnesty due to his service as postmaster at Freeo under the Confederacy, for which he was paid by the Confederate government in Confederate dollars. In an article he published in 1990 in the Arkansas Historical Quarterly regarding Johnson’s amnesty proclamation and Arkansas, historian Richard B. McCaslin notes the case of James Thompson. He states that James Thompson was the only Arkansas postmaster applying for amnesty who was not granted a pardon. The reason the pardon was withheld from him is that he did not enclose the signed oath of loyalty to the federal government that the amnesty act required.[39] After James Thompson was removed as postmaster at Freeo, Fannie Riggs operated the post office briefly, and was then followed by James’s niece Catherine Morrow Yeager, who was serving as Freeo postmistress in 1869.[40] James’s 4 August 1868 will bequeathed to Catherine, naming her as his niece, all of his estate following the death of him and wife Elizabeth.[41] The 1860 federal census shows Catherine and her husband Monroe Yeager and their family living next to James and Elizabeth Green Thompson at Freeo.

A number of documents make clear that James Thompson was removed as Freeo postmaster following the rejection of his amnesty appeal. His will contains a codicil dated 3 March 1869 stating that after his death, he wanted his executor Philip Agee to defend him in his lawsuit of the U.S. post office department against him, and noting that the U.S. post office was indebted to him in the amount of not less than $36.49, in addition to the amount of other commissions owed to him from 1 January 1856.[42]

James Makes His Will

As I’ve stated above, James Thompson made his will at Freeo on 4 August 1868 (see the image at the head of the posting).[43] The will states that he wished his body to be buried at the discretion of his beloved wife Elizabeth B. Thompson. It says that James wished for his sister Mary Martin of Randolph County, Missouri, to be paid $30 he owed her for a pony he bought in October 1827 to bring Robert Gilkinson from Kentucky to Alabama. He also wanted his nephew James Thompson, son of Andrew Thompson, paid the amount owed to him from the estate of Abigail Loster, per a decree of Ouachita County court. The will bequeathed the rest of his estate to his wife Elizabeth B., with Philip Agee as executor, and with the stipulation that after James and wife Elizabeth had died and Agee been compensated from the estate for his duties as executor, the estate was to go to James’s niece Catherine Yeager. The will has a March 1869 codicil discussed above.

Philip Agee (1802-1875) was a North Carolina-born lawyer living at Camden, the Ouachita County, seat in 1870, who was the county’s first clerk.[44] Since he predeceased James Thompson, he did not act as executor of James’s will and was not mentioned when the will was probated on 21 July 1883.

As was noted previously, since Elizabeth B. Green Thompson was living when James made his will on 4 August 1868, but James is listed as a widower living alone at Freeo on 31 August 1870 on the federal census, Elizabeth died between those two dates, almost certainly at Freeo. I have not been able to find a burial record for either Elizabeth or James. I think it’s very likely they are buried together in the White Spring Cumberland Presbyterian graveyard at Freeo, of which I cannot find any record other than its mention in a 6 March 1871 deed I’ll now discuss.

White Spring Presbyterian Deeds Church and Graveyard to A.M.E. Church

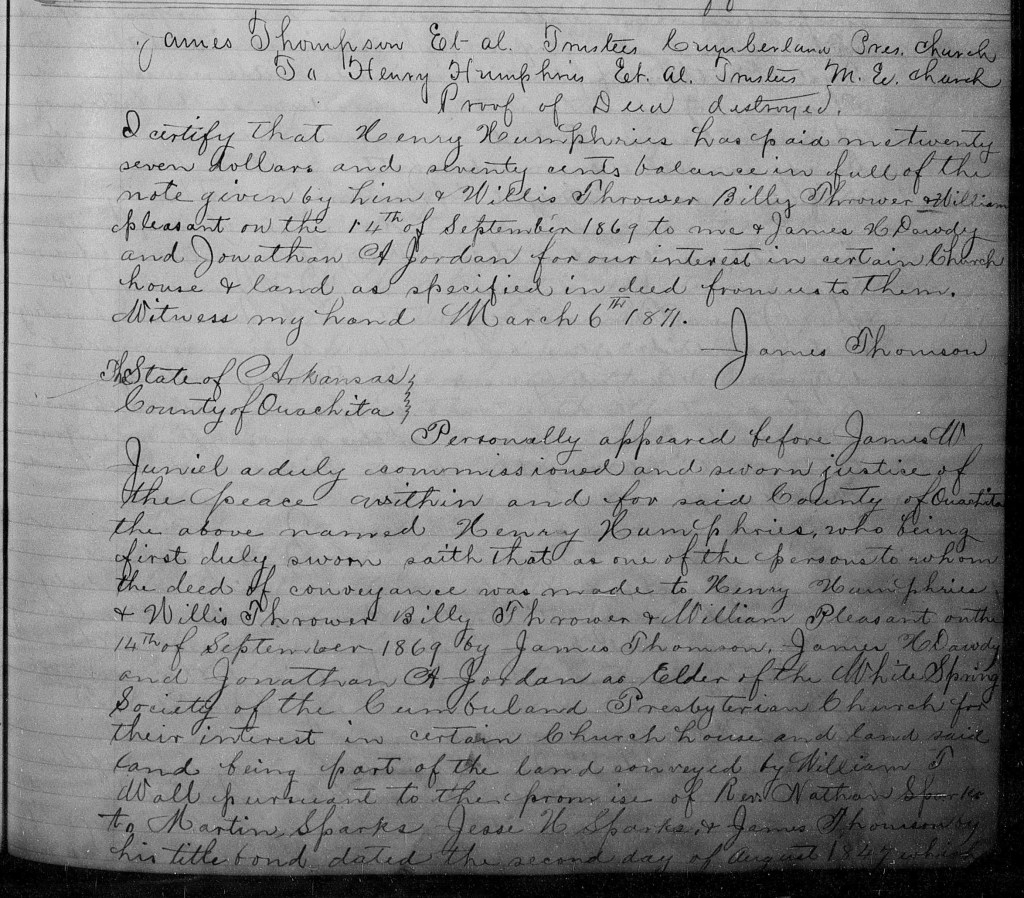

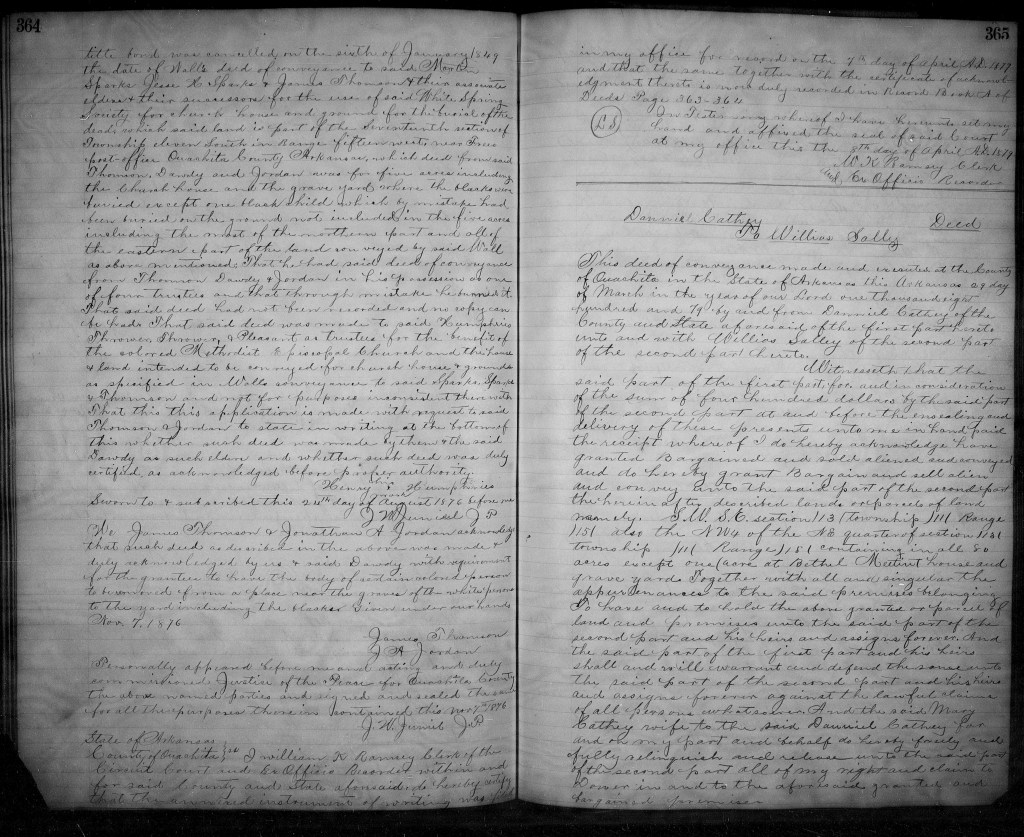

On 6 March 1871, James Thompson appears in an interesting Ouachita County deed to Henry Humphries.[45] I’ve mentioned this deed previously, noting James’s acknowledgment of it on 7 November 1876 is the last document I’ve found for him before his will was probated on 21 July 1883. The deed is headed, “James Thompson et al. Trustees Cumberland Pres. Church to Henry Humphries et al. Trustees M.E. Church, proof of deed destroyed.” The deed record begins with James Thompson acknowledging on 6 March 1871 that Henry Humphries had paid $27.70 in full of a note given by him and Willis Thrower, Billy Thrower, and William Pleasant on 14 September 1869 to James Thompson, James H. Dowdy, and Jonathan A. Jordan for their interest in a church house and land as specified in a deed from Thompson et al. to Humphries et al. This deed spells James’s surname as both Thompson and Thomson.

The deed then states that on 24 August 1876, Humphries deposed before James W. Juniel, a justice of the peace of Ouachita County, that James Thompson, James H. Dowdy, and Jonathan A. Jordan, as elders of the White Spring Society of Cumberland Presbyterian church, had made a deed on 14 September 1869 to Humphries, Willis Thrower, Billy Thrower, and William Pleasant, conveying the interest of the White Spring elders in a church house and land. The land was part of a tract conveyed by William T. Wall, pursuant to the promise of Rev. Nathan Sparks to Martin Sparks, Jesse H. Sparks, and James Thompson by a title bond dated 2 August 1847.

The title bond was cancelled 6 January 1849, the date of Wall’s deed to Martin Sparks, Jesse H. Sparks, and James Thompson and their associate elders and successors land for the use of the White Spring Society for a church house and burial ground. The land deeded to the White Spring congregation was part of section 17, township 11 south, range 15 west, and was near the Freeo post office, the deed states. Thompson, Dowdy, and Jordan had then deeded to Humphries et al. on 14 September 1869 five acres of this land with the church house sitting on it and including a graveyard “where the blacks were buried except one black child which by mistake had been buried on the ground not included in the five acres….”

Humphries deposed to Juniel that he had had the deed from Thompson et al. to him and the other named men in his possession and had burned it by mistake. The deed had been made to him, Thrower, Thrower, and Pleasant as trustees of the colored Methodist Episcopal church, and was made to them for the use of their church house and grounds.

On 24 June 1876, James Thompson wrote a notice published by the Arkansas Gazette the following day, stating that a horse had strayed from him on a visit he made to Little Rock on 27 April 1876, and he would welcome information and provide a reward to anyone writing him at the Freeo post office in Ouachita County with information about the horse.[46] The notice was written on the 24th of June. Since we know from another notice in the Gazette that James was in Little Rock in early March of the same year, I wonder if he had made an extended visit to the capital city in March and April, and if the loss of his horse occurred on the same trip that is mentioned in the March 1876 notice.[47]

As noted previously, on 7 November 1876, James Thompson and Jonathan A. Jordan, with Dowdy, acknowledged the deed of the White Spring Cumberland Presbyterian church to Humphries et al. on behalf of the African-American Methodist Episcopal church that is discussed above.[48] The acknowledgment contains the following stipulation: “with requirement for the grantees to have the body of certain colored person to be removed from a place near the graves of the white persons to the yard including the blacks.” I read this stipulation to mean that the White Spring congregation had a burying ground in which both white and Black members were buried, but in separate sections of the graveyard, and with the sale of the church and its graveyard to the African-Methodist Episcopal congregation, the White Spring trustees wanted to assure that the Black child buried in the white section was reinterred in the Black one.

I also think that the White Spring Presbyterian church had become defunct by the time it deeded its meeting house and graveyard to the African-American Methodist Episcopal church, which then seems to have taken the name of the Presbyterian church. White Springs A.M.E. church is still in existence in Ouachita County with a Bearden address, and it continues to have a cemetery. The church and cemetery are located northwest of Bearden near what was the location of the Freeo post office before it became defunct, which is where the White Spring Cumberland Presbyterian church and graveyard were also located, so the A.M.E. church appears to occupy the site of the previous Presbyterian church, and the cemetery is now known as an African-American cemetery.

A man named James Thompson appears in other Ouachita County deed records in the latter half of the 1870s and up to 12 June 1881, but in my view, this is not the James Thompson who married Elizabeth B. Green. From 1 July 1876 to 12 June 1881, there are a number of deed and mortgage records recorded in Ouachita County deed books involving a James Thompson who was indebted to Tyra Hill and Lockett & Co., in several cases jointly with William Scott. Thompson and Scott appear to have farmed together. On 2 March 1878, Tyra Hill of Camden sold Thompson and Scott 56 acres in Ouachita County, the northwest ¼ southwest ¼ of section 19, township 12 south, range 16 west, with Thompson acquiring two-thirds interest in the land and Scott one-third interest.[49]

This land was not in the vicinity of Freeo where James Thompson and wife Elizabeth B. Green lived. It was south of Freeo township in Carroll township, near where a young African-American man named William Scott with wife Mary is enumerated on the 1880 federal census in Ouachita County. Three males named James Thompson, all African-American, are also found on the 1880 census in Ouachita County. Of these, one was only a teen at the time and is not likely the James Thompson farming with William Scott by the latter half of the 1870s. One James Thompson, aged 49 in 1880, is listed as a farmer and is living in Carroll township. I think this is very likely the James Thompson farming with William Scott in Ouachita County in the latter part of the 1870s and early 1880s.

James’s Will Is Probated in Dallas County

As I’ve stated, James Thompson’s 4 August 1868 will, made at Freeo in Ouachita County, was filed for probate in Dallas County on 21 July 1883.[50] The will was filed by John B. Yeager, William C. Yeager, and Robert H. Dedman. An entry in the biographical card index file at the Arkansas Archives for James Thompson’s estate appears to indicate that the original will (as opposed to the transcribed copy in Dallas County Will Bk. D) is found in Dallas County Appraisements 1845-1890. However, as the index card also notes, the loose papers found in this collection are not in any particular order. I’ve gone through them a number of times in the digitized collection at FamilySearch, without finding the original will or any papers for James Thompson’s estate. I find no probate records for James in Ouachita County. Nor do I find in Dallas County any indication of how James’s estate was handled and settled and who inherited from him.

John Brazelton Yeager (abt. 1823-1897) was a brother of Monroe (possibly Monroe Masterson) Yeager (abt. 1818-1863), who married James Thompson’s niece Catherine Morrow. William C. Yeager was a son of Monroe Yeager and Catherine Morrow. Robert Henry Dedman (1831-1899) was a lawyer who lived at Princeton in Dallas County.

A Sketchy Sketch of James’s Thompson Family

I have not been able to identify James Thompson’s parents or place of birth in Kentucky. As I’ve indicated, James’s will tells us that he had the following siblings (and this list may not be exhaustive):

- Mary Thompson (1801-24 July 1887), who married Henry T. Martin on 2 September 1838 in Monroe County, Missouri, and is buried with him in Davis cemetery at Renick in Randolph County, Missouri. Census data place Mary’s birth in Kentucky.

- Andrew Thompson who had a son James and some connection to an Abigail Loster with ties to Ouachita County, Arkansas; I have been unable to find other information on these persons.

- Female Thompson who married a Morrow and whose daughter Catherine was born 17 September 1824 in Alabama. Catherine married Monroe Yeager, son of Abner and Sarah Yeager, on 4 January 1843 in Pulaski County, Arkansas. Catherine died 25 April 1907 in Delta County, Texas, and is buried in Lake Creek cemetery at Lake Creek in that county. After moving to Texas with some of her children, she married George H. Sigler, with whom she is buried. The fact that Catherine was born in Alabama and married in 1843 in Pulaski County makes me think she — and her parents? — may have come to Pulaski County from Alabama with James Thompson and Elizabeth B. Green. If so, I have not been able to locate information about her parents. On federal censuses reporting her parents’ place of birth, Catherine consistently reported that her parents were both born in Kentucky.

A note about the naming patterns of the children of John Green and Jane Kerr: the couple’s first son Samuel Kerr Green is named for Jane’s father, and their fourth and fifth children, Ezekiel Calhoun Green and Mary Calhoun Green, for Jane’s grandfather and mother. Since, as I’ve stated previously, I think that John Green’s father may have been a Benjamin Green who had a survey for land on 7 June 1768 in the Long Cane settlement of what later became Abbeville District or County (though I have not proven this connection), I think it’s possible John and Jane Kerr Green’s second and third children are named for John’s parents — Benjamin S. Green and Elizabeth B. Green. I note that John and Jane’s son Joscelin also had the middle initial B., so I would wonder if, back a generation earlier in the Green family line, there was a forebear, Benjamin Green’s wife Elizabeth, whose surname began with the letter B. If so, I have been unable to figure out what that B. stands for, as well as what the S. in Benjamin S. Green’s name might stand for.

[1] 1850 federal census, Ouachita County, Arkansas, Freeo township, p. 37 (dwelling/family 24; 11 November); 1860 federal census, Ouachita County, Arkansas, Carroll Union and Freeo township, p. 188 (dwelling 1304/family 1382, 21 September).

[2] Dallas County, Arkansas, Will Bk. D, pp. 246-8.

[3] 1870 federal census, Ouachita County, Arkansas, p. 283 (family/dwelling 130, 31 August).

[4] NARA, Case Files of Applications from Former Confederates for Presidential Pardons (“Amnesty Papers”), 1865- 1867, RG 94, James Thompson, Arkansas, available digitally at Fold3.

[5] See supra, n. 1 and 3.

[6] See supra, n. 1.

[7] Ouachita County, Arkansas, Deed Bk. A, pp. 363-5.

[8] See Carolyn Cox, “Freeo, Arkansas,” at the website of the Ouachita County Historical Society.

[9] See Ancestry’s database, Alabama, U.S., Marriage Index, 1800-1969, abstracting the original marriage record in Tuscaloosa County marriage records, which are not available digitally at the FamilySearch website.

[10] 1830 federal census, Tuscaloosa County, Alabama, p. 26.

[11] “Robert E.B. Baylor,” Wikipedia.

[12] Matthew William Clinton, Tuscaloosa, Alabama: Its Early Days, 1816-1865 (Tuscaloosa: Zonta, 1958).

[13] Bibb County, Alabama, Orphans Court Minutes Bk. A, pp. 190-1.

[14] Ibid., pp. 286-9.

[15] 1840 federal census, Bibb County, Alabama, p. 126.

[16] “Capital City Brevities,” Arkansas Gazette [Little Rock] (3 March 1876), p. 4, col. 3.

[17] See supra, n. 4.

[18] See, e.g., U.S. Department of the Interior, Official Register of the United States Containing a List of Officers and Employees in the Civil, Military, and Naval Service, etc. (Washington, D.C.: Gideon, 1849), p. 343; Eli Bowen, The United States Post Office Guide (New York: Appleton, 1851), p. 170; and U.S. Post Office, List of Post Offices in the United States, etc. (Washington, D.C.: Gideon, 1855), p. 49.

[19] See supra, n. 7.

[20] See Fay Hempstead, Historical Review of Arkansas: Its Commerce, Industry and Modern Affairs, vol. 3 (Chicago: Lewis, 1931), p. 1542; “Religion and the Sparks Family,” at the Sparks Family History website.

[21] Paul E. Sparks, “Nathan Sparks (1775-1844), Son of Matthew and Sarah Thompson Sparks of North Carolina, Georgia, and Tennessee, and Three Generations of His Descendants,” at the Sparks Family Association website.

[22] Thomas H. Campbell, Arkansas Cumberland Presbyterians, 1812-1984: A People of Faith (Memphis: Arkansas Synod of Cumberland Presbyterian Church, 1985), p. 67. At this time, White Spring was in Mound Prairie presbytery. Ouachita presbytery was created the following year out of Mound Prairie, and by November 1851, when the initial meeting of Bartholomew presbytery took place at Monticello, in Drew County, White Spring was in the Bartholomew presbytery (p. 75).

[23] See supra, n. 1.

[24] See supra, n. 3.

[25] See supra, n. 16.

[26] James Thompson, Sons of Temperance notice, True Democrat [Little Rock] (29 November 1854), p. 2, col. 1.

[27] James Thompson, Sons of Temperance notice, Arkansas Gazette [Little Rock] (25 October 1850), p. 3, col. 7.

[28] Arkansas Military Warrant Vol. 1058, #332.

[29] “James Fleming Fagan (1828–1893),” Encyclopedia of Arkansas (online).

[30] “Ouachita Democratic Convention,” True Democrat [Little Rock] (2 May 1854), p. 3, col. 2.

[31] “James Thompson to Editor,” True Democrat [Little Rock] (6 April 1858), p. 2, col. 1.

[32] James Thompson, Sons of Temperance notice, True Democrat [Little Rock] (09 August 1854), p. 2, col. 7.

[33] James Thompson, Sons of Temperance notice, Arkansas Gazette [Little Rock] (04 October 1856), p. 2, col. 1.

[34] “S. of T.,” True Democrat [Little Rock] (2 December 1856), p. 2, col. 4.

[35] See supra, n. 33.

[36] See supra, n. 22.

[37] Arkansas Military Warrant Vol. 919, #91.

[38] Letter of James Thompson to R.S. Yerkes & Co., True Democrat [Little Rock] (5 September 1861), p. 2, col. 6.

[39] Richard B. McCaslin, “Reconstructing a Frontier Oligarchy: Andrew Johnson’s Amnesty Proclamation and Arkansas,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 49,4 (Winter 1990), pp. 319-320.

[40] See U.S. Register of Civil, Military, and Naval Service, vol. 1 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1870), p. 329.

[41] See supra, n. 2.

[42] See supra, n. 2.

[43] See supra, n. 2.

[44] See History of Ouachita County, Arkansas; Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Southern Arkansas (Chicago: Goodspeed, 1890), p. 653.

[45] See supra, n. 7.

[46] “Strayed,” Arkansas Gazette [Little Rock] (25 June 1876), p. 4, col. 6.

[47] See supra, n. 16.

[48] See supra, n. 7.

[49] Ibid., pp. 114-5.

[50] See supra, n. 2. Dallas County court recorded the probate at its session on 15 October 1883: Probate Bk. F, p. 23.

One thought on “Children of John Green (1768-1837) and Jane Kerr (1768-1855): Samuel Kerr Green and Elizabeth B. Green Thompson”