As I’ve also noted, what I know of Samuel’s life in south Louisiana from 1822-1830 is gleaned almost exclusively from testimony given in the lawsuit his son Ezekiel filed against Samuel in Pointe Coupee Parish district court in March 1856 and from Ezekiel’s complaint initiating that legal action.[1] In particular, the testimony of Samuel’s first employers in Plaquemines Parish, Joseph B. and Catherine Andrews Wilkinson, provides important details about his life from 1822 to 1830 — about his work history in these years and about his marriage to (or marital arrangement with) Eliza Jane Smith in or around 1823 and the birth of their son Ezekiel Samuel Green in 1824 or 1825. Ezekiel’s complaint in the Green vs. Green lawsuit adds further details about this marriage and his birth.

By 1830, Samuel and Eliza Jane had gone their separate ways. As I’ll explain in a later posting, we learn this from other affidavits in Green vs. Green. In my view, Samuel and Eliza Jane were separated when she bought a family of enslaved persons from slave trader Samuel Martin Woolfolk in New Orleans on 10 May 1829: Amey, 29, and her children Baptiste/Batt, 10, Hetty, 7, and John, 4.[2] Eliza Jane used her maiden name for this transaction. Though women do frequently appear with their maiden surnames in documents in Louisiana in this period, the use of her maiden surname here suggests to me that Eliza Jane was no longer with Samuel at the time she made this purchase of enslaved persons. As we’ll see in a subsequent posting, affidavits in the Green vs. Green case indicate that by 1830, Eliza Jane was living in Iberville Parish and going by the name Mrs. Eliza Jane Green, but Samuel was not with her and she was known to be separated from him.

As the last posting also states, the Wilkinsons’ testimony in Green vs. Green states that Samuel K. Green ceased working for them in 1825 and began working for Bradish and Johnson in 1829. Ezekiel states in his complaint initiating Green v. Green that he was born in 1824 or 1825, and that his parents separated when he was five or six years old. In the period 1825-1829, Samuel and Eliza Jane were presumably together raising their young son Ezekiel. As the previous posting notes, the Wilkinsons’ affidavits regarding this period of Samuel’s life make me wonder whether he had a residence in New Orleans with Eliza Jane while he was engaged in his overseeing work in Plaquemines Parish. Ezekiel was born in New Orleans according to the death certificate of his daughter Rosa Frances Green (Holley, Anglin).

Arkansas Territory Records for Samuel K. Green

For some time, I’ve known that Samuel appears in documents in Arkansas Territory in the period 1823-9 — after he had gone to south Louisiana, as I know from the sources named above — and I have not known quite what to make of the references I’ve found to Samuel in Arkansas records in the 1823-9 period: Was he traveling there at some point during those years? If so, did he have some business interests in Arkansas Territory? If he was working for the Wilkinsons from 1822 to 1825 and for Bradish-Johnson from 1829 to 1830, was he in Arkansas Territory at some point between 1825 and 1829 — and, if so, where were Eliza Jane and Ezekiel?

As I’ve been working recently to answer those questions, I’ve made a surprising discovery, one that compels me to revise what I’ve previously written about Samuel heading to south Louisiana as soon as he left Nashville: Samuel K. Green did not go directly from Nashville to south Louisiana when he left Nashville between 1820 and 1822. He can be documented in Arkansas Territory for a brief period of time after May 1821 and into 1822.

As I’ve previously documented, Samuel was living in Nashville in 1820, when he was enumerated on the federal census of that year. A New Orleans registration record for the Nashville steamboat of which he was a co-owner, the General Jackson, shows him still owning a share in that steamboat on 7 March 1820. The posting I’ve just linked also shows that on 25 May 1820, a deed of trust from Samuel along with James Snodgrass and Isaiah Scott to Nathan Ewing for lots in Nashville had been presented in court, and on 17 January 1821, Ewing placed a notice in a Nashville paper stating that on 29 January 1820, Green, Snodgrass, and Scott, who were indebted to Joseph and Robert Woods in the sum of $5,325, had given a note for this amount to the Woods men, payable in the various Banks of Nashville in the name of Young, Green & Co., and had made a deed of trust for the four lots listed above.

The company Samuel formed with John Young when he arrived in Nashville by 1816, Young, Green & Co., is also named in the 6 June 1822 inventory of the estate of Alexander Ewing of Davidson County, which lists a note of T.H. Fletcher that had been endorsed by Young, Green. I’m fairly sure that Samuel was still in Nashville up to 7 March 1820, when he appears as a co-owner of the General Jackson as it was registered in New Orleans. I am not certain that references to Samuel in Nashville records after that date indicate he was still living in Nashville. It’s clear to me that at some point in 1820 or 1821, he left Nashville, and because he began working for the Wilkinsons in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, in 1822, I have assumed that he went directly to south Louisiana when he left Nashville.

Samuel Arrives in Arkansas Territory by May 1821

Now I learn that on 10 May 1821, Samuel K. Green was appointed a judge for an upcoming election in Richland township, Arkansas County, Arkansas Territory, and at the same time, he was appointed by the court to oversee the road from Wigton King’s to the ferry on Bayou Metre (now called Bayou Meto) in Arkansas County.[3] What Samuel was doing in Arkansas Territory at this point, I can’t say with any certainty, since references to him in the records of Arkansas County are sparse and contain no information that explains his brief residence in Arkansas Territory.

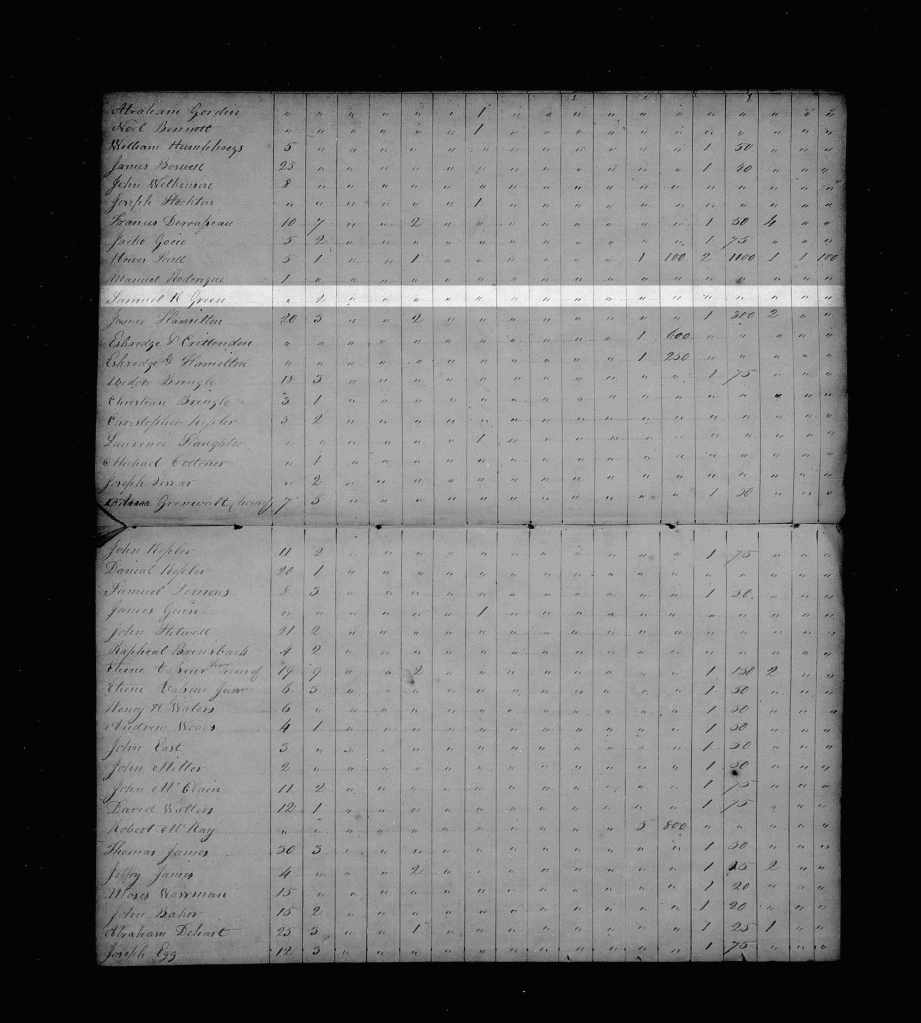

Arkansas County circuit court minutes next show Samuel K. Green serving on the county’s grand jury in February term 1822.[4] Arkansas County military assessments for 1822, a tax list of sorts, show Samuel assessed for two horses or mules and no other property in that year.[5] This is the only listing that I have found for Samuel on Arkansas County tax lists. I find him listed nowhere in land records in the brief time he appears in the county.

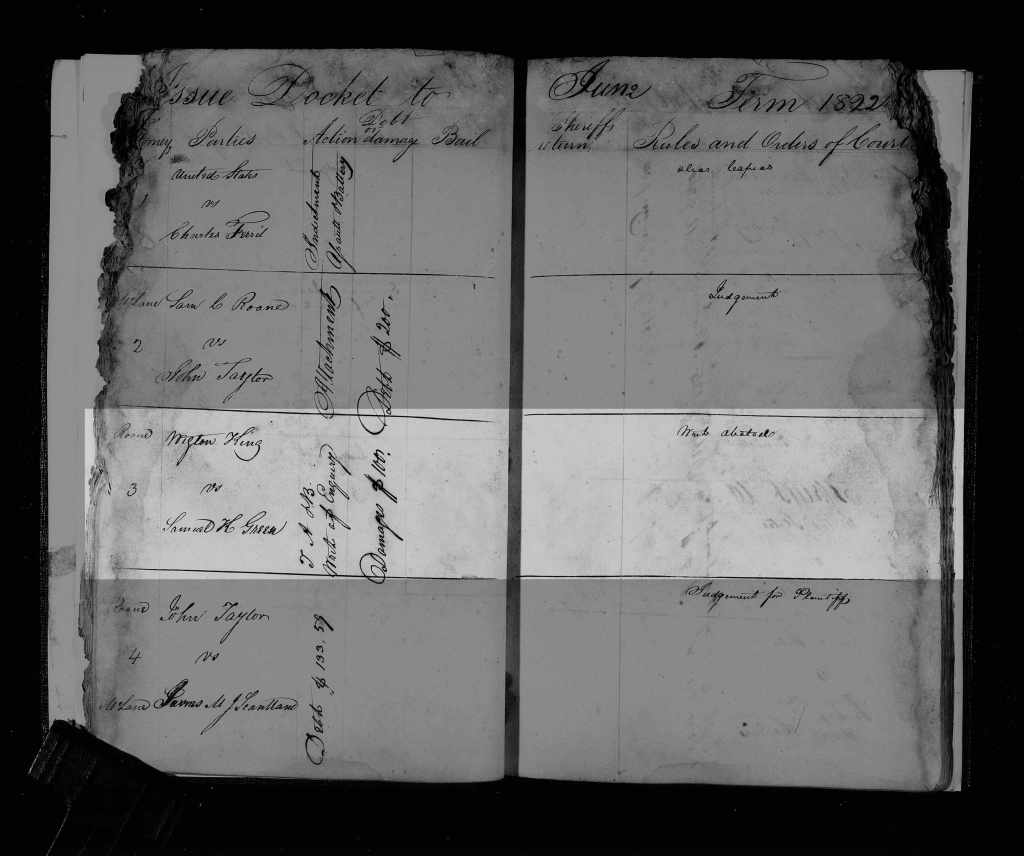

At the May (I think: see the footnote) term of Arkansas County circuit court in 1822, Wigton King, the man named previously near whom it seems Samuel was living in Richland township of Arkansas County in May 1821, charged Samuel with assault and battery, and court minutes for the term state that Samuel did not appear in court to defend himself.[6] Circuit court minutes for 11 June 1822 state that in the case of Wigton King vs. Samuel K. Green for trespass, King was to recover costs from Green.[7] This is the same case as the assault and battery case; the court issue docket for Arkansas County for June 1822 states that a writ of inquiry had been issued in the case of Wigton King vs. Samuel K. Green, a case of “T, A, & B” — trespass, assault, and battery. Assault and battery were often considered by courts of this period as trespass cases — the assault being a trespass on the person assaulted.[8] The docket states that a judgment was awarded to King for $100, and the writ was abated.

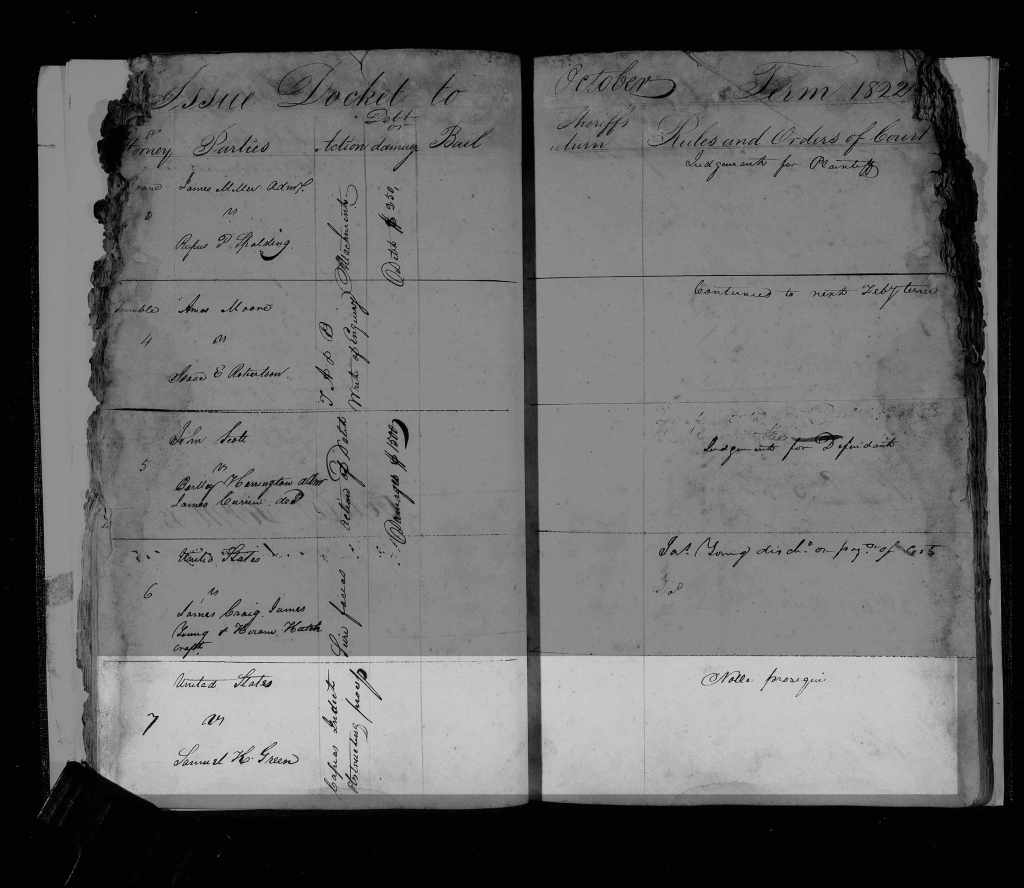

Finally, on 15 October 1822, Arkansas County circuit court minutes state that the case of United States vs. Samuel K. Green had not been prosecuted.[9] The court issue docket for Arkansas County in June 1822 also states that the case of United States vs. Samuel K. Green was no longer being prosecuted, and a capias indictment for obstruction of the legal process had been issued.[10] Since Arkansas was still a territory under governance of the United States at this point, the federal government had ultimate authority to enforce laws within the territory, and if a case was not resolved in the territorial courts at any level, it became a case prosecuted by the United States government. The case of United States vs. Samuel K. Green was the Wigton King vs. Samuel K. Green case now being referred in June 1822 to the United States government, since it had not been resolved, because, I suspect, Samuel left Arkansas Territory after May 1822 when King filed suit against him. This is why the government ceased to pursue the case, I’m inclined to conclude.

If Samuel left Arkansas Territory in or after May 1822 as my reading of these documents suggests, then it was at that point that he made his way to Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, and began his work as an overseer for Joseph B. Wilkinson. I find no further references to him in Arkansas County records after this date.

Arkansas Territory Records for Samuel, 1823-1833

However, in September 1823, another case involving Samuel appears in the minutes of Phillips County circuit court in Arkansas Territory.[11] This is the case of Samuel K. Green vs. David Adams. Phillips County adjoins Arkansas County on the east. Phillips was created from Arkansas County in 1820. These counties are in southeast Arkansas, with Phillips bordered by the Mississippi River along its east side.

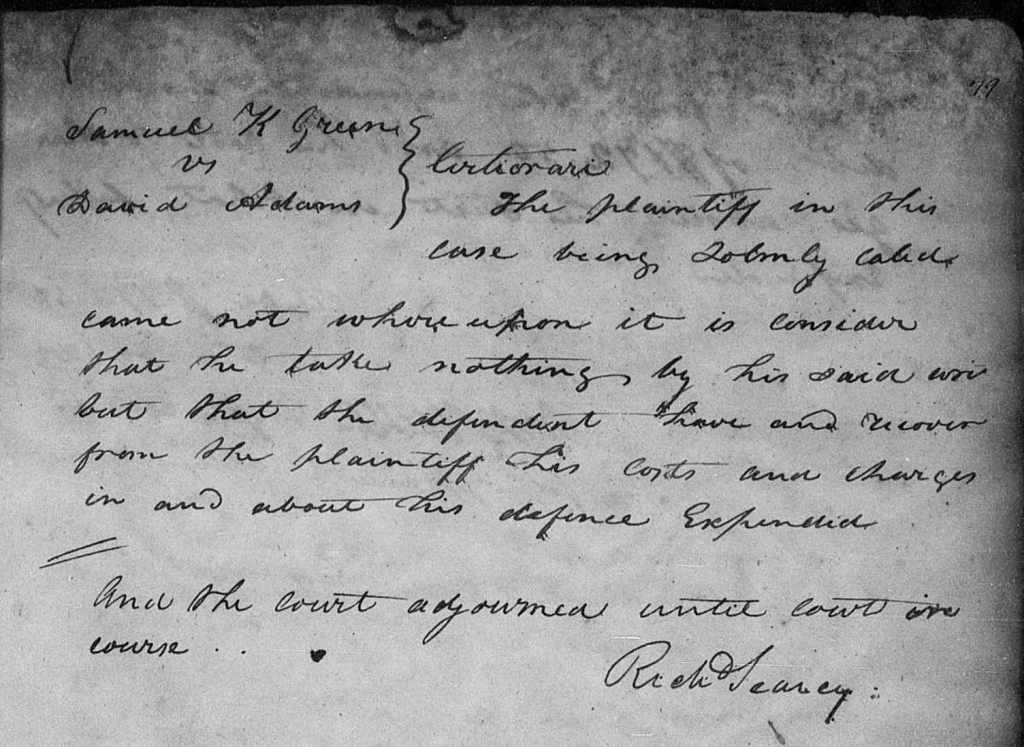

Phillips County circuit court minutes state that the case of Samuel K. Green vs. David Adams had been heard in a justice’s court (i.e., before a justice of the peace), and that the circuit court had set aside the verdict of the justice and was rehearing the case. September 1823 circuit court minutes state that Samuel K. Green was “solemnly called” but “came not,” so judgment was given in favor of Adams and Green was ordered to pay Adams’ court and defense costs.

Once again: the notation that Samuel K. Green “came not” to court in Phillips County in September 1823 after having been subpoenaed suggests to me that he had left Arkansas Territory by this point, and had gone to south Louisiana to begin his work there as an overseer. Note that this was a case that had been heard in a lower court at some point prior to September 1823 before it reached the circuit court. Phillips County circuit court minutes provide no details about the case itself. To my knowledge, there are not minutes in Phillips County recording the deliberations of justices of the peace; and county court minutes for the county postdate the date at which this case would have been heard before the county court.

David Adams lived in Arkansas County: he was an early settler of Adams’ Bluff in Arkansas County, according to Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Eastern Arkansas.[12] Adams’ Bluff was a landing on the White River about 105 miles west of that river’s mouth in Desha County, Arkansas, just south of the southern border of Phillips County.[13] Though he may have lived on the White River in Arkansas County, David Adams apparently also owned property in Phillips County, since he appears in September and December 1825 in notices in Little Rock’s Arkansas Gazette of delinquent taxpayers in Phillips County whose land was being sold for nonpayment of taxes.[14] Adams’ name appears in a list of citizens of Arkansas and Phillips County who petitioned the U.S. Congress in February 1822 for mail service from their counties to Ouachita Post in Louisiana.[15]

Note the pattern that emerges in the references to Samuel K. Green I’ve found in Arkansas Territory records in the 1820s: when he settled briefly in Arkansas by May 1821, he settled in Arkansas County, a county in southeast Arkansas closely connected to the Mississippi River by two major rivers: both the Arkansas and White Rivers flow through Arkansas County, both flowing into the Mississippi River close to each other just south of the border of Phillips County. Samuel K. Green spent the years from 1816 to 1820 or 1821 doing business as a partner in a Nashville firm that traded with New Orleans, both by flat boats and keel boats, and then by a steamboat of which Samuel was one of the pilots. We know from registration records of the General Jackson in New Orleans that Samuel piloted the General Jackson from Tennessee to New Orleans and back to Tennessee. In all likelihood, he made that trip more than once in his Nashville years. The river trade from Nashville to New Orleans took vessels west along the Cumberland River to Smithland, Kentucky, where Samuel’s brother Ezekiel Calhoun Green lived, and where the Cumberland empties into the Ohio River. Boats then voyaged along the Ohio to the Mississippi anddownriver to New Orleans, passing along the eastern counties of Arkansas including what was Arkansas County up to 1820 and then Phillips County after 1820.

There was trade into and out of Arkansas Territory by way of both the Arkansas and White Rivers, both of which run through Arkansas County and then meet the Mississippi. This trade initially involved flat and keel boats, followed by steamboats as they began to ply the Mississippi and river systems connected to it. I think the likeliest explanation for Samuel K. Green’s choice to settle initially in Arkansas County, Arkansas Territory, after he left Nashville is that he had made trading connections there during his period of engaging in Nashville-New Orleans trade, or his trips to New Orleans had given him an interest in Arkansas Territory and its economic opportunities.

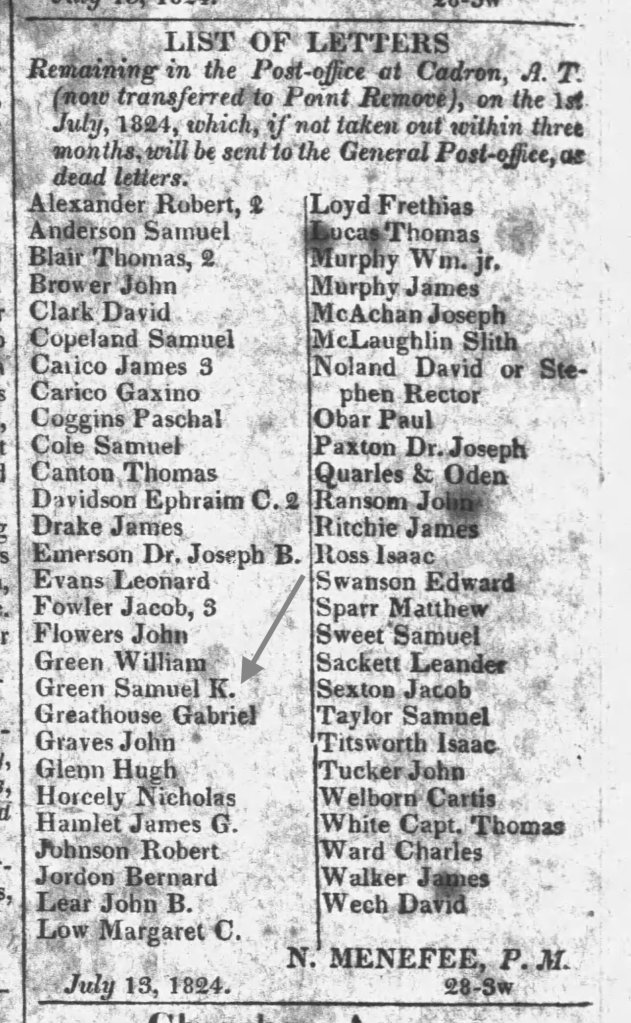

I find several more references to Samuel K. Green in records of Arkansas Territory, all of them clearly postdating his residence there. On 20 July 1824, the Arkansas Gazette published a list of those with unclaimed letters as of 1 July 1824 at Cadron post office in Arkansas Territory.[16] This listing does not, of course, mean that Samuel was actually in Arkansas Territory on that date. It could well mean that he had passed through Arkansas Territory at some point prior to July 1824 and a letter had been directed to him there by a correspondent who understood that Samuel was in Arkansas Territory. As I’ll explain in a moment, Cadron is in central Arkansas close to the Arkansas River, and had known trading ties with Arkansas County’s Arkansas Post via that river.

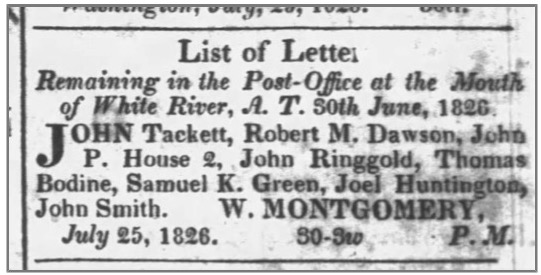

The next record I find for Samuel in Arkansas Territory records is a 25 July 1826 notice in the Arkansas Gazette that Samuel K. Green was on a list of those with unclaimed letters as of 30 June at the post office at the mouth of the White River.[17] As I stated previously, the mouth of the White River, where the White empties into the Mississippi near the point at which the Arkansas meets the Mississippi, is just south of the southern border of Phillips County.

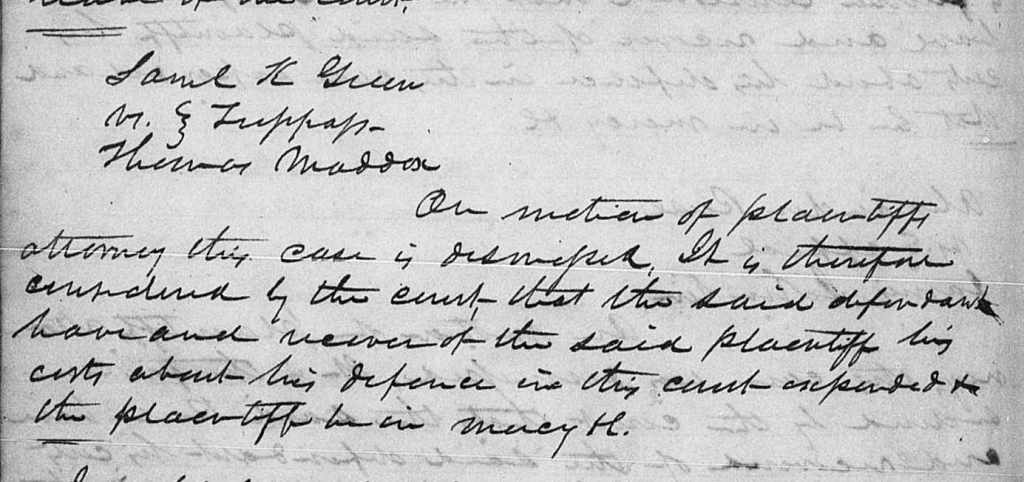

Finally, Phillips County circuit court minutes show Samuel K. Green involved in another lawsuit in that county in November 1826.[18] Court minutes for that date state that the case of Samuel K. Green vs. Thomas Maddox, a trespass case, had been dismissed on motion of Green’s attorney, with Green liable for Maddox’s court costs. I find no previous reference to this case in the county’s circuit court minutes. Note that the November 1826 court minutes indicate that Samuel was acting via an attorney: he appears not to have been in Arkansas at the time these legal deliberations were occurring.

Phillips circuit court minutes for March 1827 state that Maddox’s attorney had petitioned to have the verdict of the justice’s court, which apparently heard the case prior to the circuit court hearing, set aside, and that a new trial be held, with Maddox recovering his legal costs.[19] Court minutes for July 1827 state that both parties had appeared via their attorneys and had waived a jury trial, at which point the court rendered a verdict in Maddox’s favor with Samuel K. Green ordered to pay Maddox’s legal expenses.[20]

Court minutes for May 1828 then document the case of Bruce Percifull, garnishee of S.K. Green, vs. Thomas Maddox.[21] Once again, the previous judgment of the justice of the peace was set aside and Percifull was given judgment to recover his costs from Maddox. The same May 1828 court minutes indicate that Thomas Maddox had filed a countersuit against Samuel K. Green and Samuel was ordered to enter a plea in this case.[22] Finally, Phillips County circuit court minutes state in July 1829 that Bruce Percifull had sued Samuel K. Green as Green’s garnishee in the suit of Maddox vs. Percifull, and Green was to recover his costs from Maddox.[23]

This case was then referred to the Superior Court of Arkansas Territory, which ruled in January 1833 on the case of Chester Ashley vs. Easther Maddox, admx. of Thomas Maddox.[24] The Superior Court considered the judgment delivered by Phillips County’s circuit court and found that the lower court had erroneously awarded judgment in favor of Easther Maddox’s now deceased husband Thomas Maddox against Samuel K. Green. The circuit court issued a summons to Ashley and to Bruce Percifull, who was indebted to Green and whose note had fallen into Ashley’s hands. The circuit court had delivered judgment against Ashley and Percifull for $296.93, and the Superior Court reversed this judgment.

Bruce Percifull, who was indebted to Samuel K. Green by 1827, appears on a tax list in 1829 in Monroe County, Arkansas Territory, and is enumerated on the 1830 federal census in the same county.[25] Monroe was created from Phillips and Arkansas Counties in 1829. Along with Arkansas County, Monroe borders Phillips on the west.

A notice in the Arkansas Gazette on 7 October 1829 states that Thomas Maddox had died in Cache township in Phillips County on 20 September.[26] Other notices in the Gazette prior to this show him as a justice of the peace in Phillips County who was running for a seat on the territorial legislative council at the time of his death, and a tavern-keeper in Phillips County. The Maddoxes lived at Maddox Bay at what became Monroe County in 1829. Maddox Bay is just south and west of the White River.[27] At the formation of Monroe County, Thomas Maddox’s widow Esther offered her house for the first court hearings held in the county, honoring a plan made by her husband prior to his death.

I don’t find enough information in the court minutes pertaining to Samuel K. Green’s dealings with Thomas and Esther Maddox and Bruce Percifull to know precisely what those dealings were. Since there’s a gap of some four years between the end of Samuel’s employment with Joseph Biddle Wilkinson in Plaquemines Parish in 1825 and the start of his work for George Bradish and William Martin Johnson in 1829, it’s possible, I think, that he actually returned to Arkansas at some point during those years — though he had a wife and young son in south Louisiana by this period of his life.

Notes on Wigton King of Arkansas Post and Richland Township, Arkansas County, Arkansas Territory

Now I’d like to back up to the initial references to Samuel K. Green in Arkansas Territory I discussed previously — the statements found in Arkansas County circuit court minutes for 10 May 1821 that he had been appointed a judge for an upcoming election in Richland township of Arkansas County, and at the same time, had been directed to oversee the road from Wigton King’s to the ferry on Bayou Metre (now called Bayou Meto) in Arkansas County. These court minutes allow us to place where Samuel lived in his brief time in Arkansas Territory in 1821-2, though they don’t provide us enough information to determine what he was doing there: he lived in Arkansas County in Richland township near Wigton King and near the ferry crossing Bayou Meto, the name now used for this waterway.

Arkansas County is Arkansas’s oldest county, formed in 1813 from New Madrid County in Missouri Territory. The county is the site of the first European settlement in Arkansas, Arkansas Post, which was a trading post and settlement on the Arkansas River that became the first capital of Arkansas Territory from 1819 to 1821. Richland township, where Wigton King lived, is in present-day Jefferson County a few miles up the Arkansas River from Arkansas Post. Like Arkansas Post, the township sits on the Arkansas River with the river forming its northern boundary. Bayou Meto, which was called Bayou Metre in a number of early French documents, flows into the Arkansas River some five or six miles upriver from Arkansas Post.[28]

Samuel’s neighbor Wigton King was a resident of Arkansas Post by 1814, according to Josiah Shinn, though he later became a planter in Richland township in what was Jefferson County after 1829.[29] King signed a 4 January 1819 petition of residents of Arkansas County to Congress for Arkansas Post to be made the territorial capital of Arkansas.[30] The petition informed Congress that Arkansas Post was “a place of considerable business and an increasing population” and was the only town in the southwest section of Missouri Territory, located some fifty miles from the mouth of the Arkansas River. At the time he signed this petition, Wigton King was probably already living in Richland township, since the executive register for Arkansas Territory shows him being commissioned a magistrate of that township on 3 November 1819.[31]

I haven’t found clear information regarding Wigton King’s origins. In 1810, he was enumerated on the federal census in Adams County, Mississippi, so he evidently arrived at Arkansas Post from there. He came to Arkansas Territory with a checkered past. Prior to his arrival in Arkansas, he had been a trader among the Chickasaws in Mississippi and Tennessee, where he earned a reputation for being, in the words of historian James R. Atkinson, “a deceitful, self-serving white man.”[32] Atkinson notes that at some point during his years among the Chickasaws, King taught Chickasaw youth at a school set up by James Robertson.

James Hendry Miller Jr. echoes James R. Atkinson’s assessment of Wigton King’s character, noting that he was “an unscrupulous but ambitious interpreter” for the Chickasaws who informed Chickasaw leaders in September 1814 (after he arrived in Arkansas Territory) that he had the blessing of the U.S. Secretary of War to be the new federal agent to the Chickasaws — a fabrication.[33] Chickasaw leaders responded by stating that King possessed “no standing” among them and professed that their “nation will not Receive him if apointed [sic].”[34] On 2 September 1814, Joseph Allen wrote James Madison to oppose Wigton King’s appointment to replace James Robertson as agent to the Chickasaw Nation.[35] Andrew Jackson characterized King as unreliable in correspondence dealing with Chickasaw matters, and an 8 April 1814 letter of Turner Boarhears, assistant federal Indian agent, to Secretary of War John Armstrong states that King was a liar, drunk, and traitor.[36]

Some of what underlay the hostility of the Chickasaws to King is apparent in a 22 September 1816 letter that William Cocke, U.S. agent to the Chickasaws, sent to Secretary of War William H. Crawford on 22 September 1816.[37] Cocke stated that Chickasaw leaders had met on 17 April after hearing that James Colbert was going to bring Wigton King along with him to D.C. when Colbert and Chickasaw leaders went as a delegation to the federal capital. The Chickasaws were opposed to King being part of the delegation, since they had requested he be removed from their nation for “malconduct.” The Chickasaws thought that Colbert and King were seeking to arrogate all the trade of the Chickasaw Nation to themselves. Colbert denied this and said that “no man of King’s character should travel with him” — though, in fact, he did bring King along as an interpreter on this trip.

Records of the Indian trading house on the Chickasaw Bluffs from 1803-1818 show King trading with the Chickasaws in West Tennessee during these years. At an unspecified date that may have been 1806, he was paid by the federal government for transporting goods from “Shipping Port, Kentucky” to the Chickasaw Bluffs Factory. Chickasaw Bluffs Factory was a federal government-run trading house on the Chickasaw Bluffs overlooking the Mississippi River on the site that was later to become the city of Memphis.[38]

After settling in Arkansas Territory, King continued his connection to the native peoples via the federal government: in the latter part of the 1820s, he taught Quapaw boys at his house.[39] The government paid King handsomely for this work: on 6 January 1832 he was paid $1,230 for boarding Quapaw youths at his house in the period 1 July 1828 to 30 June 1830.[40]

Wigton King died of cholera aboard the steamboat Arkansas on 19 June 1833 as he returned from a trip to New Orleans.[41] He was living at Richland township in Jefferson County, Arkansas Territory, at the time of his death.

Arkansas Post

Given Samuel K. Green’s location as suggested by the sparse records documenting his time in Arkansas Territory in 1821-2, I think it’s very likely that what drew him to Arkansas was Arkansas Post, which experienced a brief period of economic promise and growth in the period from around 1817 to 1821. As Kathleen DuVal notes, Arkansas Post “was the first and most significant European establishment in Arkansas. In the colonial and early national periods, from 1686 to 1821, it served as the local governmental, military, and trade headquarters for the French, the Spanish, and finally the United States.”[42]

French officer Henri de Tonti, who served under René-Robert Cavalier, Sieur de La Salle, in his 1682 expedition, was rewarded for his service with land and a trading concession at the meeting point of the Arkansas and Mississippi Rivers. This would be the first French settlement west of the Mississippi River. In the summer of 1686, de Tonti arranged with the Quapaws living beside the Arkansas River for a number of his associates, all Frenchmen, to establish a trading post at Ecores Rouges on the river in what would later become Arkansas County. The post did business with New Orleans and places further north including Detroit, trading French goods for animal pelts.[43] In 1763 Arkansas Post came under Spanish rule, and in 1804, the Spanish ceded the Post to the United States.

Following this, the U.S. established a military presence at Arkansas Post, and from 1805-1810, there was an official U.S. trading “factory” operated by government factor John B. Treat at the Post. The federal trading post, which limped along and was ultimately a failure, dealt mainly in pelts and traded with both Detroit and New Orleans.[44]

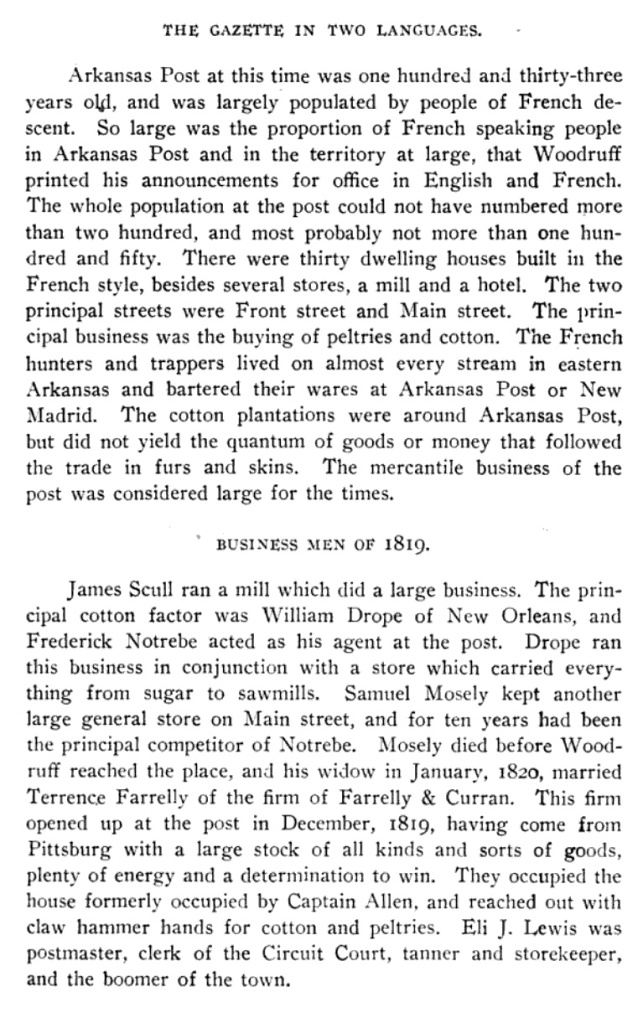

Following the demise of the federal trading post, French native Frederic(k) Notrebe established himself as a businessman at Arkansas Post in 1817, and the previously torpid settlement of French traders, trappers, and, occasionally, soldiers began to experience an economic and demographic boom.[45] Notrebe set up a dry-goods store at the Post and opened a cotton plantation with labor of enslaved persons, inaugurating the Arkansas market for cotton in 1819.[46] As Kathleen Cande notes,

Frederick Notrebe was a prominent merchant, planter, and land speculator at Arkansas Post (Arkansas County). One of the wealthiest men in territorial and antebellum Arkansas, he operated a trading house, dealing mostly in furs and peltries. As one of the first cotton factors at Arkansas Post, he was instrumental in establishing cotton as a staple crop in territorial Arkansas.

In the years of Arkansas Post’s boom from 1817 to 1821, the region around it became, as Theodore Catton indicates, an arena for land speculators.[47] As Roger E. Coleman states, the demise of the government factory at the Post followed by Notrebe’s arrival “heralded a new economic era at Arkansas Post in which “[a]n agricultural economy slowly supplanted the waning fur trade.[48] Coleman adds that the influx of farming families in the countryside around it changed life at Arkansas Post in this period significantly.[49] He writes,[50]

Instead of dealing in pelts, Arkansas Post merchants now catered to farmers. Eli J. Lewis, William Drope, and Frederic Notrebe transacted nearly all the post business. The village of Arkansas Post now boasted a mill and one hotel. Several Americans joined the French and Spanish to live in the village. The number of civilian residents now totaled nearly two-hundred, larger than any other time during the existence of Arkansas Post.

As Theodore Catton points out, when English traveler Thomas Nuttall first visited Arkansas Post in February 1819, he recorded unfavorable impressions of it in his diary.[51] The following year in January 1820, he came again to Arkansas Post and was surprised at the significant changes that had taken place there in the previous year. In 1819, he had seen “an insignificant village [that] scarcely deserved geographic notice.” But in 1820, Nuttall noted the following:[52]

Interest, curiosity, and speculation, had drawn the attention of men of education and wealth toward this country. Since its separation into a territory; we now see an additional number of lawyers, doctors, and mechanics. The retinue and friends of the Governor together with the officers of justice, added also essential importance to the territory, as well as the growing town.

When Congress established Arkansas as a territory on 2 March 1819, Arkansas became the territory’s capital and “[t]he village on the Arkansas prospered as the territorial capital.”[53] On 30 October 1819, William E. Woodruff arrived at Arkansas Post from Brooklyn, New York, and established the Arkansas Gazette, the first newspaper west of the Mississippi, at the Post.[54] The Gazette began publication on 20 November 1819, and the Post’s inhabitants were jubilant: as Coleman states,[55]

Civilization had at last come to Arkansas. So overjoyed were the inhabitants that the community celebrated the first publication of the Arkansas Gazette with a barrel of whiskey donated by a merchant. With the presence of public officials and lawyers in the community, all of whom rented space for living quarters and offices, land values soared. Many part-time lawyers engaged in land speculation. In 1818, the Town of Rome, adjoining Arkansas Post, was platted by William Russell, a lawyer. Russell divided the town into 44-consecutively numbered lots, 2 of which were set aside as sites for public buildings. He hoped Rome would become the new county seat. In anticipation, many residents bought lots as an investment. In 1819, William O. Allen, also a lawyer, platted the Town of Arkansas adjoining Rome. Post residents were so certain of the future of Arkansas, that a board of trustees was elected for the newly platted town.

Soon after this at the end of March 1820, the first steamboat to come upriver from the Mississippi, the Comet, reached Arkansas Post, and upriver trading posts including the army garrisons at Fort Smith and Fort Gibson provided a ready market for supplies from the post. The arrival of steamboats also provided enhanced access to New Orleans markets, causing the prices of merchandise at the Post, much of it brought upriver from New Orleans, to drop overnight and the demand for farm produce shipped from the Post to New Orleans to increase dramatically.[56]

Then in 1821, the territorial capital moved from Arkansas Post to Little Rock, some 100 miles up the Arkansas River at a spot on higher ground considered more healthy than the flat land on which Arkansas Post was constructed — and also more centrally located in the state-to-be — and the Post’s boom went bust. As Kathleen DuVal notes,[57]

When Arkansas became a territory in 1819, Arkansas Post, as its largest and most important town, became its capital. As settlers moved into regions north, west, and southwest of the Post, however, the population center shifted from the Post. In 1821, the capital moved to the new town of Little Rock (Pulaski County).

Roger Coleman describes the effects of the move as follows:[58]

The relocation devastated the economy of Arkansas Post. Government officials and lawyers departed as did William Woodruff with his printing press. Because of this population exodus, land values slumped, and many landowners were unable to pay taxes. The towns of Arkansas and Rome, platted in a fever of speculation, were never fully developed.

William Woodruff and his Arkansas Gazette made the move to Little Rock along with the territorial government, but Frederic(k) Notrebe remained at Arkansas Post, dying in New Orleans on 4 April 1849 of either cholera or pneumonia.[59]

Just as the shift of the territorial government from Arkansas Post to Little Rock took place, another relative of mine, Thomas James, was voyaging up the Arkansas River in 1821 with a group of traders from St. Louis, and noted the following:[60]

Ascending the Arkansas, the first settlement we reached was “Eau Post,” inhabited principally by French. A few days afterwards we arrived in the country of the Quawpaws, where we met with a Frenchman named Veaugean, an old man of considerable wealth, who treated us with hospitality. His son had just returned from hunting with a party of Quawpaws and had been attacked by the Pawnees, who killed several of his Indian companions. Pawnee was then the name of all the tribes that are now known as Camanches. I had never known or heard of any Indians of that name before I visited their country on my way to Santa Fe. The Americans previously knew them only as Pawnees. The account brought by Veaugean’s son surprised me, as we had heard that all the Indians on our route were friendly. Leaving Veaugean’s, we proceeded up the river through a very fertile country. Dense and heavy woods of valuable timber lined both sides of the river, both below “Eau Post” and above as far as we went, and the river bottoms, which are large, were covered by extensive cane-brakes, which appeared impenetrable even by the rattlesnake. Small fields of corn, squash and pumpkins, cultivated by Indians, appeared in view on the low banks of the river. Since entering the Arkansas we had found the country quite level; after sailing and pushing about three hundred miles from the mouth, we now reached the first high land, near Little Rock the capital of the Territory as established that spring. The archives had not yet been removed from Eau Post, the former capital.

As footnotes to this text when it was published in 1916 by the Missouri Historical Society, “Eau Post” was Au Poste or the Poste aux Arkansas, and the M. Veaugean who offered hospitality to James and his comrades was François Nuisment Vaugine.

A 25 March 1817 letter published in Nashville’s Clarion and Tennessee State Gazette, by a French emigrant then visiting Arkansas Post and writing to a friend in St. Louis From Arkansas Post, describes what this writer, tagged as “distinguished and enlightened,” saw as the possibilities of Arkansas Post and its environs in 1817.[61] The letter writer spoke of the “admirable fertility” of land along the Arkansas River, which the writer judged to be “without doubt the most beautiful and agreeable part of the U. States, both in temperature of climate and fertility of soil.” As this letter notes, mail had been established between Arkansas Post and St. Louis, and its inhabitants were also seeking mail service to the Ouachita region of Louisiana. You could reach New Orleans from Arkansas Post in ten or twelve days in a keel boat, and could return from New Orleans in a keel boat in 35-40 days. About the Arkansas River, the letter writer stated,

I have never seen any river whose navigation is equal to that of the Arkansas. It can be ascended in a loaded boat at the rate of three hundred miles in twelve days. With scarcely any other expence than that of horses, there might be relays established on the banks, by which means boats might be drawn up as fast as the mail travels. The shallows are hard bottom, wide, and naturally kept clear by the current. There are neither rapids nor dangerous rocks. The river is as beautiful as the Seine, and only wants a Rouen or a Paris in miniature.

I doubt seriously that at any point in its interesting history Arkansas Post ever in any way rivaled Paris. But I suspect that Samuel K. Green may have gone to Arkansas County in Arkansas Territory initially after leaving Nashville in 1820 or 1821 because he was aware that Arkansas Post had been experiencing a boom and that this opened up promising trading opportunities including continuation of his Nashville trade with New Orleans.

Unfortunately, he arrived in Arkansas Territory just as the territorial capital was being transferred from Arkansas Post to Little Rock, and as the Post was losing the luster it had acquired in the period from 1817 to 1820 — and these developments may well have been part of his decision to leave Arkansas Territory for New Orleans by 1822. Whatever his conflict was with Wigton King, that conflict and King’s lawsuit against Samuel may also have spurred Samuel to move to south Louisiana.

The Cadron Settlement

A final note about the Cadron settlement at whose post office an unclaimed letter addressed to Samuel K. Green was waiting on 1 July 1824 as noted above: this is the one location in records I’ve found for Samuel in the 1820s that was not in southeast Arkansas. Cadron is in central Arkansas north of Little Rock, and was linked to Arkansas Post via the Arkansas River and the trading interests of Notrebe at Arkansas Post, who did business with the Cadron settlement.[62] As David Peterson and Bill Norman note, the Cadron settlement was the first permanent white settlement in central Arkansas, and was near the confluence of Cadron Creek and the Arkansas River.[63] The settlement began around 1818 as land speculation rose in central Arkansas was seriously considered by the legislature of Arkansas Territory as the state capital until that honor was given to Little Rock in 1821. A 24 December 1818 memorial to the U.S. Congress from the House of Representatives of Missouri Territory calls for the establishment of a postal route from the Cadron post office on the Arkansas River to the place where courts were held in Pulaski County (of which Little Rock is the county seat), and from there to “the little rock.”[64]

The Cadron post office was established in 1820 and took mail to and from Arkansas Post every other week. As the history of the Cadron settlement found online at University of Central Arkansas’s FranaWiki states,

By 1820 the settlement had 717 residents, compared with 1,923 in Pulaski County as a whole. (Cadron was then part of Pulaski County.) On June 28, 1820, the first General Assembly of Arkansas Territory located county government in the town of Cadron. The Assembly approved the construction of a jail and courthouse on October 23, 1820, but these were not built. On October 21, 1821, acting territorial governor Robert Crittenden approved the removal of the county seat to Little Rock.

Cadron became a leading candidate for the site of the Arkansas state capitol. On February 22, 1820, Joab Hardin drafted a bill making Cadron the site of the capitol. This bill was rewritten in committee to redirect the site to Little Rock, but was tabled by the legislature. When the new legislature convened in the fall, a new bill naming Little Rock the capitol was passed. The governor signed this bill into law on October 21, 1820.

Given its trading ties with Arkansas Post and the connection of the two places by the Arkansas River, and the fact that Arkansas Post seems likely to have been what attracted Samuel K. Green to Arkansas Territory when he left Nashville, it’s interesting that he seems to have had a connection to the Cadron settlement at some point in the 1820s, perhaps during his brief sojourn in Arkansas. He was not in Arkansas any longer when an unclaimed letter was waiting for him at Cadron post office in July 1824. But some acquaintance who knew that Samuel had been in Arkansas earlier in the 1820s and had spent time at Cadron may well have sent this letter to him prior to July 1824.

[1] Ezekiel S. Green vs. Samuel K. Green, Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana, 9th District Court, file #1525.

[2] Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, Notarial Bk. 4, #714, p. 276 (Register 17, #4, p. 714).

[3] Arkansas County, Arkansas Territory, Circuit Court Minute Bk. 1819-1829, 10 May 1821, pp. 49-53. The digitized copy of this minute book at the FamilySearch site is under lock and key. I am relying on an abstract of this minute book done in 1972 by the Grand Prairie, Arkansas, chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution: see Grand Prairie Chapter, Records of Arkansas County, Arkansas, vol. 76 of Arkansas Genealogical Records (1972), online at Family Search. This abstract gives the name of the man appointed an election judge in Richland township as Samuel P. Green, but the index to the collection of abstracts gives his name as Samuel K. Green — and I think that, since the same abstract contains other references to Samuel K. Green and none to a Samuel P. Green, that the K. initial is correct for this May 1821 record: this is Samuel Kerr Green.

[4] Arkansas County, Arkansas Territory, Circuit Court Minute Bk. 1819-1829, February 1822, pp. 75-8, per the Grand Prairie DAR abstract cited supra, n. 3.

[5] Arkansas County, Arkansas, Military Assessments, 1822, unpaginated.

[6] Arkansas County, Arkansas Territory, Circuit Court Minute Bk. 1819-1829, May? 1822, pp. 86-92. The DAR abstract cited supra, n. 3, does not provide a date for this record other than 1822; the context suggests May.

[7] Ibid., pp. 94-5.

[8] Arkansas County, Arkansas Territory, Issue Docket, June 1822.

[9] Arkansas County, Arkansas Territory, Circuit Court Minute Bk. 1819-1829, 15 October 1822, pp. 108-114.

[10] Arkansas County, Arkansas Territory, Issue Docket, October 1822.

[11] Phillips County, Arkansas Territory, Circuit Court Bk. A, pp. 75-6, 79.

[12] Biographical and Historical Memoirs of Eastern Arkansas (Chicago, Nashville, St. Louis: Goodspeed, 1890), p. 635.

[13] Louis A. Adams, Adams Directory of Points and Landings in the South and Southwest (New Orleans: Murray, 1877), p. 2.

[14] “Lands for Sale for Taxes in Phillips County,” Arkansas Gazette (6 September 1825), p. 5, col. 1; and “A List of Delinquents,” Arkansas Gazette (6 December 1825), p. 3, col. 4.

[15] Clarence Edwin Carter, ed., The Territorial Papers of the United States, vol. 19: The Territory of Arkansas, 1819-1825 (Washington, D.C.: Govt. Printing Office, 1953), pp. 400-1. The petition was submitted to Congress on 4 February 1822.

[16] “List of Letters,” Arkansas Gazette (20 July 1824), p. 4, col. 4.

[17] “List of Letters,” Arkansas Gazette (25 July 1826), p. 3, col. 5. The list was published again in the Gazette on 8 August 1826.

[18] Phillips County, Arkansas Territory, Circuit Court Bk. B, p. 10.

[19] Ibid., p. 28.

[20] Ibid., p. 39.

[21] Ibid., p. 71.

[22] Ibid., p. 73.

[23] Ibid., pp. 85-6.

[24]Ashley et al. v. Maddox, Superior Court of Arkansas Territory #18,227, January 1833; see The Federal Cases: Comprising Cases Argued and Determined in the Circuit and District Courts of the United States from the Earliest Times to the Beginning of the Federal Reporter, Arranged Alphabetically by the Titles of the Cases and Numbered Consecutively, Book 30 (St. Paul: West, 1897), pp. 955-6. I have looked for this case in Phillips County circuit court minutes, 1821-1830, without finding it. The original minutes have a gap from 1828-1830.

[25] 1830 federal census, Monroe County, Arkansas Territory, p. 101.

[26] Arkansas Gazette (7 October 1829), p. 3, col. 2.

[27] Louise Mitchell and David Sesser, “Monroe County,” Encyclopedia of Arkansas; and Jo Claire English, “A Brief History of Monroe County,” at the USGenweb site for Monroe County.

[28] Staff of Encyclopedia of Arkansas, “Bayou Meto,” Encyclopedia of Arkansas.

[29] See Josiah Shinn, Pioneers and Makers of Arkansas (Washington, D.C.: M.C. Shinn, 1908), p. 66, noting the marriage of King’s daughter Mary to Samuel Mosely, a native of Scotland, at Arkansas Post on 22 October 1818. Shinn says King had been living at Arkansas Post from 1814 and was a j.p. up to the creation of Arkansas Territory.

[30] Charles Edwin Carter, The Territorial Papers of the United States, vol. 19: The Territory of Arkansas, 1819-1825 (Washington, D.C.: Govt. Printing Office, 1953), pp. 21-3.

[31] Ibid., p. 802.

[32] James R. Atkinson, Splendid Land, Splendid People: The Chickasaw Indians to Removal (Tuscaloosa: Univ. of Alabama Press, 2004), p. 217.

[33] James Hendry Miller Jr., “Southern Intrusions: Native Americans and Sovereignty in the Early Republic,” unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Florida State University, 2017, p. 56; available digitally at website of Florida State University.

[34] Ibid., citing a letter of Chinabbie King et al. on 9 September 1814, in NARA, Records of the Chickasaw Agency, Correspondence, 1812-1818: Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Record Group 75, folder 1, box 1, entry 1058. On Wigton King’s character, Miller cites Atkinson, Splendid Land, Splendid People, pp. 204-205, 217-218; and William Cocke to James Winchester, 17 February 1815, NARA, Records of the Chickasaw Agency, Correspondence: Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs 1812-1818, RG 75, folder 1, box 1, entry 1058.

[35] Daniel Preston, ed., Comprehensive Catalogue of the Correspondence and Papers of James Monroe, vol. 1 (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood, 2001), p. 415.

[36] See United States War Department, The War of 1812 U.S. War Department Correspondence, 1812-1815, ed. John C. Frederiksen (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2016), p. 41, citing the original letter in the NARA collection of Choctaw Agency papers.

[37] American State Papers Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States, vol. 6 (Washington, D.C.: Gales and Seaton, 1834), p. 107.

[38] See Mary Louise Graham Nazor, “The Indian Trading House on the Chickasaw Bluffs, 1803-1818,” Tennessee Genealogical Journal/Ansearchin’ News 47,4 (winter 2000), p. 12, abstracting information from Chickasaw Bluffs’ Indian Factory Ledgers, 1803-1818, from NARA, Records of the Bureau of lndian Affairs: Selected Documents among the Records of the Office of lndian Trade Concerning the Chickasaw Bluffs Factory, RG 75, pp. 482, 519. See also “Chickasaw Bluffs Factory Ledger,” a digitization of the original ledger available at the University of Memphis Digital Commons site.

[39] Joseph Patrick Key, “Sarasin (?-1832?),” Encyclopedia of Arkansas.

[40] See “Indian agents, Letter from the Secretary of War, transmitting copies of accounts of persons charged with the disbursement of money, &c., for the benefit of the Indians from the 1st October, 1831, to 30th September, 1832,” in H.R. Doc. No. 137, 22nd Cong., 2nd Sess. (1833), available digitally at the University of Oklahoma Law School’s Digital Commons site.

[41] Harry D. Alvis, “1830-1850, Jefferson County Arkansas Pioneers,” at the Jefferson County, Arkansas, USGenweb site.

[42] Kathleen DuVal, “Arkansas Post,” Encyclopedia of Arkansas.

[43] Theodore Catton, A Many-Storied Place: Historic Resource Study, Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas (Omaha: National Park Service, 2017) On Tonti’s trading house, pp. 76-83.

[44] See ibid., pp. 144-9; and Edwin C. Bearss and Lenard E. Brown, Arkansas Post National Memorial: Structural History, Post of Arkansas, 1804-1862, and Civil War Troop Movement Maps, January 1863 (Washington, D.C.: Department of The Interior, National Park Service, 1971), pp. 21-31.

[45] DuVal, “Arkansas Post.”

[46] Ibid., and Kathleen H. Cande “Frederick Notrebe (1780–1849),” Encyclopedia of Arkansas.

[47] Catton, A Many-Storied Place, p. 155.

[48] Roger E. Coleman, The Arkansas Post Story: Arkansas Post National Monument (Santa Fe: National Park Service, 1987, available digitally at the website of the National Park Service.

[49] Ibid., citing Morris S. Arnold, Unequal Laws unto a Savage Race: European Legal Traditions in Arkansas, 1686-1836 (Fayetteville: Univ. of Arkansas Press, 1985), p. 187.

[50] Coleman, The Arkansas Post Story, citingBearss and Brown, Arkansas Post National Memorial, p. 19; and

[51] Catton, A Many-Storied Place, p. 158.

[52] Ibid., and Coleman, The Arkansas Post Story, citing Thomas Nuttall, A Journal of Travels into the Arkansas

Territory, During the Year 1819 (Philadelphia: Palmer, 1819), pp. 109, 292-3.

[53] Coleman, The Arkansas Post Story.

[54] Shinn, Pioneers and Makers of Arkansas pp. 11-19.

[55] Coleman, The Arkansas Post Story.

[56] Ibid., and Catton, A Many-storied Place, p. 162.

[57] DuVal, “Arkansas Post.”

[58] Coleman, The Arkansas Post Story.

[59] Cande, “Frederick Notrebe (1780–1849).

[60] Thomas James, Three Years Among the Indians and Mexicans (St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society, 1916), pp. 98-100.

[61] “Interesting Views of Our Country,” The Clarion and Tennessee State Gazette (12 August 1817), p. 3, col. 3-4.

[62] See “Cadron Settlement Park” at University of Central Arkansas’s FranaWiki; and Margaret Smith Ross, “Cadron: An Early Town That Failed,” Arkansas Historical Quarterly 16,1 (spring 1957), pp. 3-27, noting the ties of William Drope, who was closely connected to Frederic(k) Notrebe in the trading buiness of Arkansas Post, to Cadron.

[63] David Peterson and Bill Norman, “Cadron Settlement,” Encylopedia of Arkansas.

[64] Clarence Edwin Carter, ed., The Territorial Papers of the United States, vol. 15: The Territory of Louisiana-Missouri (Washington, D.C.: Govt. Printing Office, 1951), pp. 483-4.

2 thoughts on “Samuel Kerr Green (1790-1860): Arkansas Territory Records, 1821-1833, and Brief Sojourn in Arkansas, 1821-2”